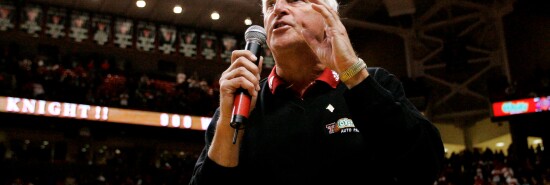

Bobby Knight, 1940-2023

Daniel Ross Goodman

Once upon a time in sports, coaches were the absolute monarchs of their teams, exerting total control over every aspect of their clubs while at the same time playing the role of benevolent dictators toward their players. While they sought to provide sage advice to their charges, they also ensured that those they were mentoring knew their places and would never deign to challenge them. When football, baseball, basketball, and hockey went from simply being organized pastimes and developed into multibillion-dollar industries, coaches realized they could no longer hold autocratic sway over players who were making more money than they were, and they adjusted their coaching styles accordingly.

But in college sports, in which up till very recently players were unable to make any money at all and the athletes were also students — and therefore subject to discipline by their teachers — coaches were able to rule over their teams with iron fists for far longer than their professional sports counterparts. When modern media began to spotlight some of the worst abuses of these coaches, the great majority of college coaches felt pressured into reforming their authoritarian ways. One of the holdouts who resisted as long as he could was Bobby Knight, the imperious and legendary college basketball coach, who died this month at 83.

Robert Montgomery Knight was born and raised in northeast Ohio and went to college at nearby Ohio State University, where he played on the Buckeyes’ 1960 NCAA championship-winning basketball team. Upon graduating, Knight immediately went into coaching, taking a job as an assistant coach at the U.S. Military Academy and soon thereafter becoming head coach at Army at age 24, the youngest NCAA Division I head coach in the country at that time. After six successful seasons at Army (among his players at West Point was future Duke coach Mike Krzyzewski), in 1970, Indiana University hired Knight in the hopes of reviving its then-flagging basketball program. Knight fulfilled its hopes in grand fashion, restoring the Hoosiers to their primacy of place not only in the Big Ten but in college basketball overall.

Knight led Indiana to an NCAA championship in 1976, going undefeated while doing so. No Division I basketball team has had a perfect season since. Knight would go on to helm the Hoosiers to two more national championships (in 1981 and 1987), 11 Big Ten championships, and 24 NCAA tournament appearances. “The General,” as he was sometimes called, was named Associated Press coach of the year three times, broke North Carolina coach Dean Smith’s all-time Division I wins record, and, in 1991, was unanimously elected to the Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield, Massachusetts.

Knight, however, was as volatile as he was successful. Notorious as much for his tirades as for his trademark red sweater, Knight’s litany of browbeating included unremitting cursing at players and referees, throwing a chair onto the court in the middle of a game, and an apparent choking of one of his players. When, in 1997, Knight angrily grabbed the arm of one of his players because the player had failed to address him as either “Coach” or “Mr. Knight,” Indiana University President Myles Brand had finally had enough. Brand fired Knight. It was a move that would always remain controversial in basketball-obsessed Indiana, no matter how justified it may have been. And it left one of the preeminent coaches in the sport to finish out his career at the mid-tier college basketball program of Texas Tech University.

That Knight was able to hold on to the kind of power he had for so long, and exert it so tyrannically over his players and the entire Indiana University basketball program and, indeed, the state itself, is a testament to how successful of a coach he was. When lesser coaches began to be subjected to media scrutiny for their highhanded ways, college athletics directors had no qualms about replacing these mediocre despotic coaches with more enlightened new-age coaches. After all, perhaps bringing in a coach from a new generation with more civilized views of the player-coach relationship could also bring the program more wins and a newfound level of respect. But what if the seemingly uncivilized, brutish, backward basketball coach is also one of the greatest at his craft in the entire country? If you are a college athletic director, how do you justify getting rid of one of the winningest coaches not only in your program’s history but in the history of all college sports? Such was the dilemma faced by Indiana University for much of the latter part of the career of one of the more complex anti-hero coaches in the history of sports.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Daniel Ross Goodman is a Washington Examiner contributing writer and a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard Divinity School. His latest book, Soloveitchik’s Children: Irving Greenberg, David Hartman, Jonathan Sacks, and the Future of Jewish Theology in America, was published this summer by the University of Alabama Press.