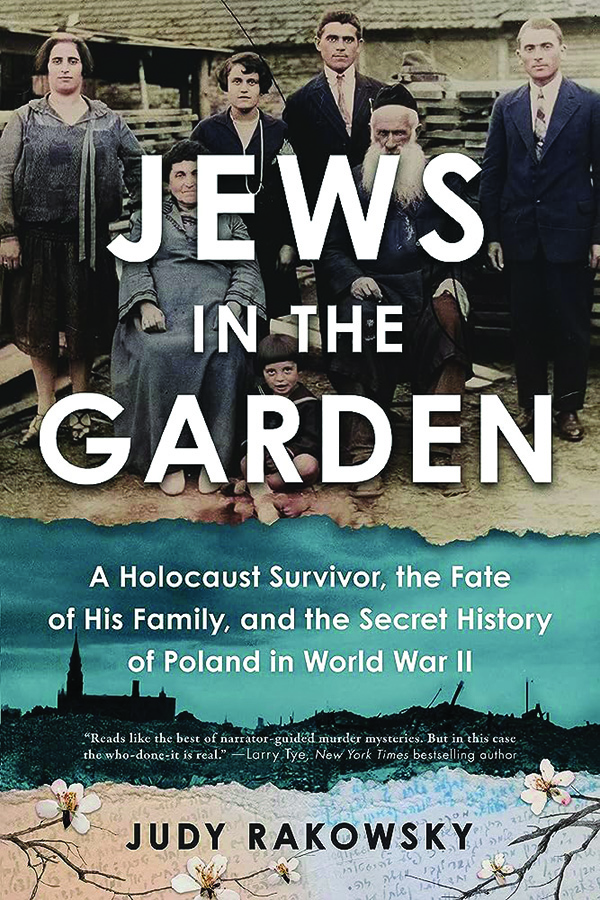

Reviewed: Jews in the Garden: A Holocaust Survivor, the Fate of His Family, and the Secret History of Poland in World War II

Sean Durns

“Part of remembering,” historian David Blight once observed, “is forgetting.” Perhaps nowhere is this truer than the nation of Poland, where so-called memory wars have been waged over the country’s role in the Holocaust. These battles are at the heart of Judy Rakowsky’s new book, Jews in the Garden: A Holocaust Survivor, the Fate of His Family, and the Secret History of Poland in World War II.

A veteran reporter who spent years covering everything from organized crime to priest sex abuse scandals, Rakowsky uses her journalistic talents to cover the greatest crime of the 20th century. This is, appropriately enough, a detective story. Both Judy and her cousin and research partner Sam are determined to find out not only how their family died, but also who was responsible. Sam helps anchor the story. Born in Poland, he survived the Holocaust before heading to Israel and eventually the United States. Clearly a remarkable man, his charisma is apparent on nearly every page. Sam, Rakowsky writes, “may be a survivor, but he was no victim.”

MATTHEW GOODWIN ANALYZES POPULISM FROM THE INSIDE

Along the way, they learn that Poles, not Germans, murdered their cousins, including a family that was mercilessly gunned down after spending more than a year hiding in a barn. One of them, however, survived, watching from a short distance as her family was massacred. Judy and Sam’s search for that lost cousin leads them to uncover some bitter truths about the country from which their family hails.

Yet Sam is also haunted. Much of the book revolves around his deep desire to be remembered as not only Jewish but also Polish. Decades after the trauma of the Holocaust, he still grapples with how neighbor could turn on neighbor. Despite all that he has gone through, he is clearly an optimist, keen to see the best in people. Sam hopes that old acquaintances in Poland will help uncover what happened to his cousins. Sadly, he is in for disappointment. What they discover is a nation unwilling to come to terms with its past.

Poland’s World War II history is both tragic and complicated. As part of the infamous Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union carved up the country. The subsequent Nazi invasion kicked off World War II in Europe.

Poland, home to many of the continent’s Jews, would become the “prime theater for history’s most systematic extermination of humans,” Rakowsky notes. Indeed, all six death camps were built on occupied Polish territory. In total, the Nazis constructed 44 concentration camps, but they “confined the killing factories to Polish turf.”

In the 1930s, Poland’s legislature passed laws that kept Jews out of certain jobs, including in universities and the medical and legal fields. And like in Germany, restrictions were also put in place in universities. Boycotts, many of which escalated to violence, were enacted.

But Poland was also unique among other nations occupied by the Nazis. Unlike many other countries, Poland’s government went into exile instead of cooperating with the Nazi occupiers. Numerous Poles gave aid to Jews, offering everything from food to shelter. More Poles were named “Righteous among the Nations,” an honor bestowed by Israel’s Yad Vashem for non-Jews who risked their lives during the Holocaust to save Jews, than people of any other nationality. This, too, is part of the story of Poland and the Holocaust. And many, like Sam, never forgot it.

Sam “remembered every wartime kindness shown to him by a Pole, from the supervisor in the German motor pool who tipped him off about the impending roundup of Jews in 1942 to the forewoman in the metal factory where he was a slave laborer while in the Krakow ghetto who piled finished goods on his workstation, lightening his workload by helping him meet his quota.”

However, even among the Polish resistance to the Nazi occupiers, there is a darker side. Some resistance groups actively targeted and murdered Jews, including Judy and Sam’s family members. This happened far more frequently than many, including some prominent Polish politicians and intellectuals, would like to admit. Many murderers never faced justice.

Others materially benefited from the systemic annihilation of Poland’s historic Jewish community. In wartime Poland, Rakowsky observes, “these killers had an extra motive to act because murder enabled them to steal Jews’ possessions and divide the spoils among themselves.” And here, too, justice has long been denied.

As Rakowksy points out: “The Polish government has never compensated Jews for all the homes and businesses that were seized by the Germans and then kept by the communist government” that took over at war’s end. When Sam’s mother and sister sought to return home after liberation, they were attacked by locals.

When the country was under communist rule, it adopted a position that omitted Jews from the World War II narrative. Monuments and textbooks failed to mention the Holocaust. In this retelling of history, the tragedy and losses endured by the Polish nation and people are elevated, while the genocide of its Jews is hidden.

One key factor, Rakowsky notes, is Poland’s “historic narrative of victimhood.” Throughout history, the nation had been broken up and torn apart by foreign conquerors. As one researcher told the author, this led to an “obsession with innocence” and the nation’s conviction that it is “morally blameless thanks to its resistance and widespread suffering, with millions killed” in World War II. Yet the “martyr identity” has led to a refusal to admit any culpability.

“Poles,” Dariusz Stola, the director of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews, observed, “lost the war. They lost a lot: family members, cities, libraries, churches, 20% of their territory, and national independence. Little was left but their innocence. … When you lose everything, it’s good to at least be innocent.”

For a moment in the early 2000s, it seemed that the country would finally account for what had happened. In 2001, Polish American historian Jan T. Gross published Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland, which highlighted the complicity of certain Poles and Polish groups in the systematic murder of Polish Jews. The exhaustively researched book briefly prompted a reexamination, including investigating commissions and apologies. But the moment proved fleeting.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Poland would make a U-turn, with its leaders passing libel laws targeting those who dared to “defame” Poland by dredging up the role of certain Poles and Polish groups in murdering Jews. Poland also passed laws that prevented heirs from obtaining restitution for property that had been taken by Germans and kept by Poles. Polish politicians who failed to go along sometimes lost government grants and reelection bids. In 2015, Gross himself was charged with libel. The case was later dropped. However, other historians still face similar pressures should their research turn up facts that are deemed inconvenient.

This is the backdrop of Judy and Sam’s search for both the truth and their family. And it is inescapable. Yet, as Stola said: “We are not responsible for what happened 70 years ago, but we are responsible for what we do with the past today. And I think the right thing to do is talk about it.” Jews in the Garden does precisely that, expanding the conversation in a manner that is at once disturbing and haunting.

Sean Durns is a senior research analyst for CAMERA, the 65,000-member Boston-based Committee for Accuracy in Middle East Reporting and Analysis.