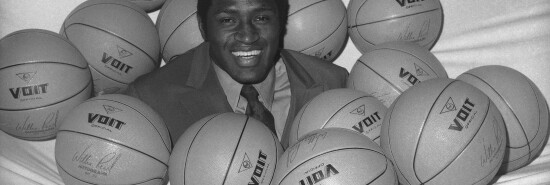

Willis Reed, 1942-2023

Daniel Ross Goodman

Most athletes who become all-time greats acquire their immortality through many years of consistent top-level performance. But there are others who become immortal in a single moment. Such was the case with Willis Reed, the center — and centerpiece — of the great New York Knicks teams of the 1970s. Reed died this week at the age of 80.

Reed was born in 1942 in small-town Louisiana, and raised nearby. He stayed local for college, attending Grambling State, then was taken by the Knicks in the 1964 NBA draft.

Reed’s immortality-achieving moment occurred six years later, in the winner-take-all Game 7 of the 1970 NBA Finals. The Knicks were playing a juggernaut Los Angeles Lakers team that boasted eventual Hall of Famers Jerry West, Elgin Baylor, and — most significantly — Wilt Chamberlain, basketball’s Goliath and the then-leading scorer in NBA history. West, Baylor, and Chamberlain were each regarded (and still are considered) three of the greatest players in the history of basketball. The Knicks, by comparison, were a little engine that could, a team that shared the ball, that could shoot, pass, dribble, rebound, and execute all the technical components of the game well, but were without the kind of truly dominant player that most championship teams are typically built around. Reed, Walt Frazier, Dave DeBusschere, and Bill Bradley were all fine players, but none of them could approach the individual greatness of West, Baylor, or Chamberlain. That the Knicks had managed to push the Lakers to a Game 7 was a remarkable feat enough.

Although the Knicks epitomized “team” in contrast to the Lakers’ star-studded approach, the Knicks still relied on Reed to set their offense and anchor their defense. The Knicks especially needed Reed to try to stymie Chamberlain — or at least ensure that he wouldn’t score over 50. (Chamberlain once averaged 50 points in a season, something still almost unfathomable in spite of the spate of 50-point games the NBA has seen this season.) Prior to Game 7, however, Reed had suffered a painful leg injury — it was later revealed that he had torn his right quadriceps muscle — and it was doubtful that he would be able to play. Without Reed, the Knicks, who were trying to win their first NBA Championship, seemed doomed to fall short of the ultimate prize.

Just before tipoff, however, the capacity crowd at Madison Square Garden roared — Willis Reed could be seen making his way out of the locker room and out onto the court. “Here comes Willis!” a young Marv Albert exclaimed on the telecast, the first (and perhaps still most famous) of Albert’s many celebrated calls. Shortly after tipoff, the left-handed Reed hit his first shot; the New York crowd roared as if they had all been promised rent-controlled apartments. Moments later, Reed, dragging his right leg up and down the court like a prisoner with a ball and chain attached to his leg, hit another shot; the crowd roared again. Reed didn’t score for the rest of the game. He didn’t need to. Frazier and the rest of the Knicks took over the game and, feeding off the raucous energy of Madison Square Garden at one of its absolute apex moments, carried the Knicks to their first NBA Championship. Reed, who had just won the regular season Most Valuable Player award, was named Finals MVP. But no trophies could encapsulate what that moment meant to Knicks fans and to sports lovers across the nation. It was Washington crossing the Delaware on a basketball court, a moment that changed the course of a franchise and that was immortalized on the canvas of every Knicks fan’s heart.

The Knicks were dreadful when Reed arrived in 1964, a fact that perhaps gives hope to younger Knicks fans today that a one-man miracle may yet arrive in their lifetimes too.

Daniel Ross Goodman is a Washington Examiner contributing writer and the author, most recently, of Somewhere Over the Rainbow: Wonder and Religion in American Cinema.