The child is the mother of the woman

Peter Tonguette

These days, according to the powerful yet unidentified cultural commissars who one imagines dictating trends in the thinkpiece sphere, it seems everything is a spectrum, except morality, which is binary.

Consider the curious case of Woody Allen, who was canceled more thoroughly than most after decades-old allegations of sexual abuse of his adopted daughter became mysteriously newly relevant during the #MeToo era, a cultural and journalistic trend concocted in no small part by his alleged biological son, journalist Ronan Farrow. Not only did the A-list casts who once clamored to work with him develop a sudden reticence, but the few films he has managed to make in the meantime — A Rainy Day in New York, Rifkin’s Festival — have barely been seen. His forthcoming picture, Coup de Chance, was not only filmed in France but in French, a strange indignity for a writer who had mastered the comic contours of the English language.

By the same token, Mia Farrow — Allen’s former companion, leading lady, and the adoptive parent, with Allen, of Dylan Farrow, who, as a child, lodged the abuse allegations against Allen — is presented as a kind of Mother Teresa to her brood of natural-born and adopted children. Her only sin was to choose a romantic companion and filmmaking mentor who, by her and most of her family’s lights, betrayed her and them.

Factions have formed: The anti-Woody, pro-Mia contingent can imagine neither a scenario whereby Woody could be (conceivably) a bad man and a great artist nor one in which Mia could be (theoretically) a sympathetic figure, certainly a wronged woman, but mistaken in her allegations. The smaller but equally passionate pro-Woody, anti-Mia camp glosses over the undeniable sleazy circumstances of the formation of his romantic relationship with Soon-Yi Previn. Soon-Yi is often popularly but wrongly understood to be another adoptive Woody-Mia child, though in fact, she was the charge of Farrow and her second husband, Andre Previn. She and Allen started an affair when she was 20 or 21 and then formed a lasting marriage.

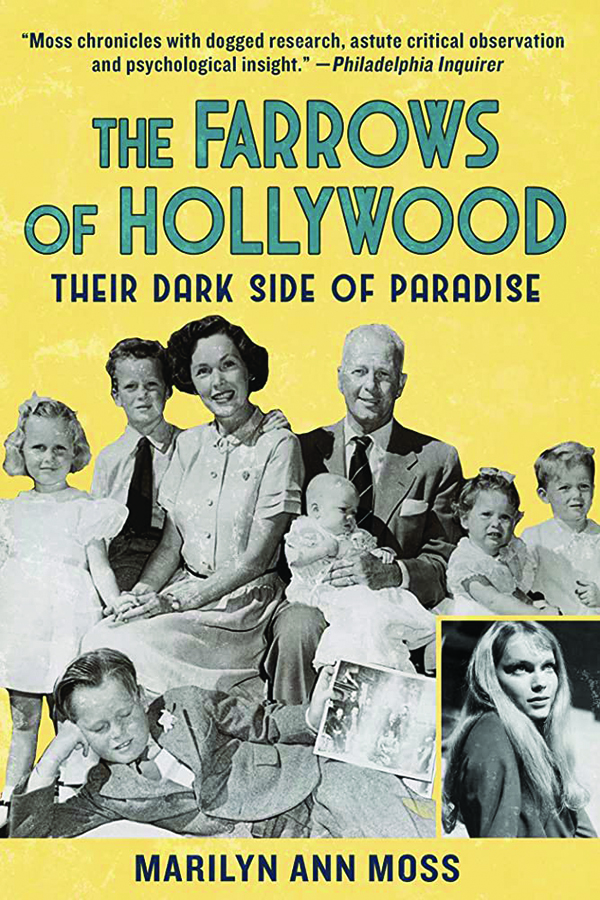

This sort of “up-or-down vote” mentality arguably reached its apex in the 2021 HBO documentary Allen v. Farrow, the very title of which assumes that a quasilegal framework is the only way to approach the matter: With a trial comes the promise of definition and finality. Real life, outside a courtroom, is far messier. Happily, film scholar Marilyn Ann Moss embraces the messiness of real life in an astonishingly good new book, The Farrows of Hollywood. Released by vigilante independent publisher Skyhorse, which picks up books institutions want canceled but readers want released, this volume delves into the sad, strange history of the Farrow family. It serves as a useful reminder that nearly everyone has closets with skeletons.

Moss writes in her introduction, “My interest lies with understanding some of the psychological warfare that embraced the Farrow family.” Put more plainly, Moss refrains from explicitly aligning with either the pro- or anti-Mia camp but instead means to complicate, and thereby enrich, our understanding of Mia.

The first foreshadowing of Mia’s adult life, namely, what is generally thought of as her voracious maternal instinct, was set in motion before her birth: Her parents, director John Farrow and actress Maureen O’Sullivan, had seven children, of which Mia was the third. John Farrow was a formidable filmmaker with a genuine gift for lively adventure stories and jet-black film noirs, and O’Sullivan was a beauty so bewitching that she charmed Tarzan (she was cast as Jane). Both were Catholics; Farrow, a particularly forceful convert. “They were called the pretty ones, the beautiful Farrows,” Moss writes. “For many, especially those who knew them from a distance, the family must have lived a fairy-tale life. After all, they had looks, money, and movie star prestige.”

But you know what they say about looks and deception. O’Sullivan was not quite the warm materfamilias one would suppose. According to a childhood friend of Mia’s, Moss writes, “Maureen loved having children, but after giving birth she had absolutely no idea what to do with them.” John Farrow had a reputation not just for artistry but also for tyranny. During the making of his comedy Red, Hot and Blue, Farrow apparently asked a female singing coach if he could make incisions on her arm with a knife: “Just a few small ones. It couldn’t matter to you much.” There is an account here of Farrow needlessly calling for retakes of a scene involving the flogging of an actor, a compulsion the filmmaker admitted he couldn’t deny himself: “It’s just that I couldn’t stop; I was enjoying it all so much!”

Farrow’s family, large though it became, was apparently not spared his shabby behavior. In her own memoir, Mia wrote of an evening in which her father “charged my mother with a long knife through the ground floor rooms” and described severe paternal punishment via a walking stick. He is described as an insatiable philanderer — at one point, O’Sullivan demanded that he have an exterior door built into the bedroom he occupied at home — and one affair brought him near an abyss of violence: He is said to be the father of an illegitimate child by a woman he met through one George Hill Hodel Jr., a suspect in the Black Dahlia murder case.

Contrasting sharply with this strange combination of licentiousness and brutality was his intensely committed Catholicism, seen by some as a cover. “He was a professional Catholic, Farrow,” said Robert Mitchum’s secretary, Reva Frederick. “Always surrounded by nuns and priests. But his private life was entirely different.” Ray Milland, an actor who worked with him, said that he “had a touch of masochism about him,” while Mitchum, with whom the director shared a love of drink, said he was a “sadist.” Moss, a perceptive critic of Farrow’s films, concedes this temperament suited one of his favorite genres: “Noir was his natural palette; sinister his zone.”

Farrow died in 1963, but by then, the damage had been done. Sister Prudence became a true believer in Transcendental Meditation, fell under the spell of the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, and now is reported as living “off a dirt road in a mobile home” in Florida. Others were genuinely tragic figures: One brother, Patrick, killed himself, and another, John Charles, served time in prison for sexually abusing two boys.

And what of Mia? With just a dash of armchair psychology, Moss writes that Mia sought to summon the memory of her father in numerous relationships, including her first marriage to Frank Sinatra, “a dictator just as John Farrow had been.”

At first blush, the neurotic and skinny Woody Allen seems an odd surrogate for Mia’s domineering father. But Moss writes, plausibly, that both “lived by their own beliefs, not entirely by society’s order.” Moss describes Woody’s affair with Soon-Yi with a proper sense of the relationship’s boundary-pushing quality, not unlike John Farrow’s infidelities. “Once more, in an odd way, Mia had found in Woody another father replacement.”

Moss tries to place herself inside Mia’s head as she processes this transgression, but the author is sanguine about what she doesn’t know and can only speculate about. She writes of the way Mia’s description of Woody’s favoritism toward Dylan weirdly mirrors Mia’s account of her fatherly (but slightly romantic) friendship as a girl with actor Charles Boyer. Moss asks whether it could “be possible that in a state of extended trauma Mia is displacing something from the past onto something in the present?” She also notes that Dory Previn, Andre Previn’s ex-wife, suggested to Woody that Mia’s allegations curiously echo a song Dory wrote, which foreshadowed the setting of the alleged abuse: “In the Attic with Daddy.”

Mia’s own children have in large part remained loyal to her, but her adopted son Moses asserted that she herself committed physical abuse and came to cast his lot with Woody. Two other adopted children committed suicide. “It was not a happy home — or a healthy one,” Moses said.

What to make of this? “We should assume that Mia believes the stories she’s been telling,” Moss concludes. “Beyond that, all we know for certain is that Mia had a father named John Farrow who left his kids a childhood that still determines their lives.” After reading this rigorously researched, perceptively written book, however, we know one other thing for sure: in the Woody-Mia contretemps, only a fool would try to find the moral high ground. “What a mess” is a more sensible reaction than any firm feeling about the parties’ innocence or guilt, let alone virtue or sinfulness.

Peter Tonguette is a contributing writer to the Washington Examiner magazine.