Our nuclear weapon paradoxes

Mackubin Owens

Thanks to the international box-office success of Oppenheimer, the use and morality of nuclear weapons have become a popular discussion again. While we have lived in the nuclear era for the better part of a century, nuclear escalation and deterrence policy remains at the forefront of any military confrontation, including with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. That campaign has played out against the backdrop of modern nuclear weapons technology and the fear that Russia might escalate to nuclear levels in order to break the stalemate in its favor. Yet the technological advancements in nuclear weapons, and indeed, non-nuclear weapons, since the time of Robert Oppenheimer might make it less likely either side will resort to a grand nuclear clash.

On Aug. 6, 1945, an American aircraft dropped an atomic bomb over Hiroshima, Japan. Three days later, a second bomb was detonated over Nagasaki. The two bombs killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians. The debate over the morality of these bombings began immediately and has only intensified over the decades as the destructive power of nuclear arms increased with the development of a thermonuclear weapon.

WHAT HARRY TRUMAN DIDN’T KNOW ABOUT THE NUCLEAR BOMB

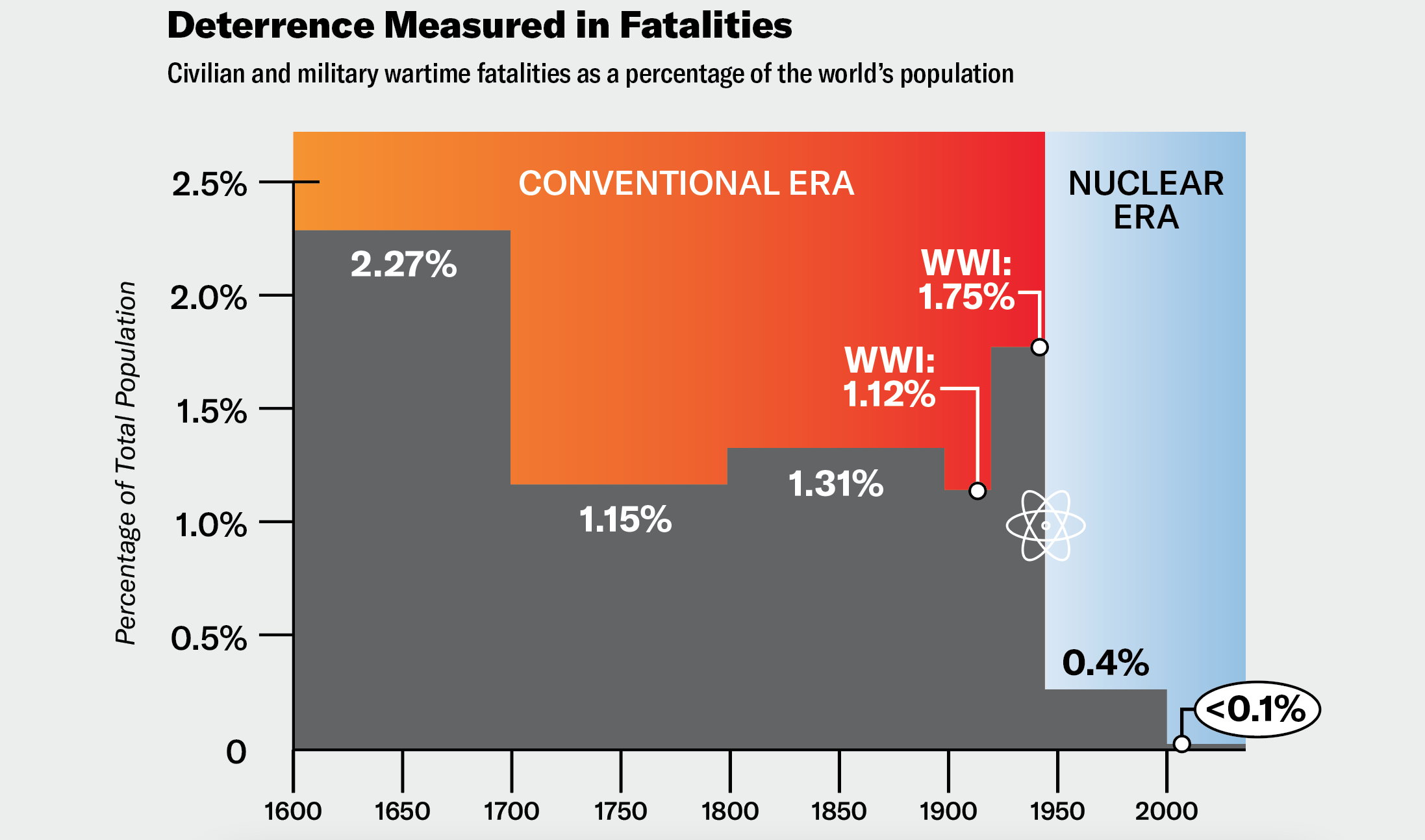

Supporters of President Harry Truman’s decision to use the bomb cite the likely human costs of the alternatives: a blockade of Japan intended to starve the Japanese into submission, hardly a humanitarian course of action, or an invasion, which would have killed many more Americans but also Japanese as well. And any discussion of the morality of nuclear deterrence since the end of World War II has to take account of the fact that, although the Atomic Age did not lead to the end of war, fear of the destructive power of nuclear weapons placed an upper limit on conflict. One has only to compare the human cost of war since 1945 to the years between 1914 and 1945.

Nuclear weapons very likely prevented war between the United States and the Soviet Union. Indeed, during the Cold War, nuclear weapons policy and strategy suffused every aspect of national security, including non-nuclear strategy. The great destructive power of nuclear weapons served as a deterrent. For instance, the U.S. rejected military options during both the Korean and Vietnam wars out of concern that escalation might lead to a nuclear confrontation with the Soviet Union or China.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine and NATO’s proxy war have raised the specter of a possible nuclear confrontation between the U.S. and Russia. Certainly, Putin has rattled the nuclear saber. He previously warned against Western interference with his assault on Ukraine and put Russian nuclear forces on alert. With his invasion of Ukraine having bogged down recently, he ratcheted up his threats to employ nuclear weapons. U.S. officials have taken that threat seriously, voicing concerns that Russia might employ tactical or low-yield nuclear weapons in response to setbacks in Ukraine.

It is customary to classify nuclear weapons as “strategic,” capable of striking assets in the enemy’s homeland; “theater,” capable of striking strategically important targets within a theater of operations; and “tactical,” intended to attack enemy units or weapons in relatively close proximity to one’s own forces. Strategic weapons have generally featured a higher “yield” of explosive power.

In the early years of the Cold War, the main means of delivering a strategic weapon was a gravity bomb dropped by an aircraft. Next came ballistic missiles, both land- and sea-based. These were of intercontinental range, meaning that the U.S. could attack targets in the Soviet Union and vice versa. The U.S. ultimately deployed a nuclear “triad” consisting of strategic bombers, such as the B-52 and B-2, land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles, and submarine-launched intercontinental ballistic missiles. The Soviet arsenal followed a similar pattern. At the theater and tactical level, delivery systems included aircraft, cannon artillery, and intermediate-range ballistic missiles. Today, cruise missiles and hypersonic missiles have been added to the mix.

U.S. nuclear weapons policy during the Cold War was based on the logic of an “escalation ladder.” The main theater of war in the confrontation between the U.S. and the Soviet Union was Europe. U.S. and NATO policymakers believed that they could not match Soviet and Warsaw Treaty Organization conventional forces in Europe, but according to the logic of escalation, NATO could deter war by threatening to use tactical nuclear weapons, such as low-yield weapons delivered by aircraft, tube artillery, and short-range missiles, if it were in danger of losing a conventional conflict. If WTO responded in kind, NATO could escalate to theater-level nuclear weapons and, if necessary, to the strategic level.

In the early years of the Cold War, U.S. policymakers believed that the U.S. possessed “escalation dominance”: that in any scenario, conventional or nuclear, the U.S. could threaten to escalate to a level of conflict at which we possessed the advantage. That belief evaporated in the 1970s as the Soviets began to deploy theater nuclear weapons and, most critically, to develop powerful counterforce strategic nuclear capabilities, such as the SS-18, that erased U.S. escalation dominance. A U.S. threat to escalate to a nuclear exchange as it was losing a conventional war in Europe now rang hollow.

Beginning in the late 1970s and into the Reagan administration, the U.S. responded in three ways: at the strategic nuclear level, deploying a whole array of new, accurate land-based and sea-based systems such as the Minuteman III, the MX, and the Trident Missile and the first components of a system of strategic defense; at the theater nuclear level, deploying the Pershing II intermediate ballistic missile in Europe; and perhaps most importantly, at the conventional level, developing true war fighting and war winning operational doctrines for the U.S. Army and Air Force, AirLand Battle/Operations, and for the naval services, the “Maritime Strategy,” was designed to bring naval aviation to bear against NATO’s northern flank and in the Pacific.

With the end of the Cold War, the central importance of nuclear weapons to U.S. security policy declined precipitously. Of course, there were concerns about rogue actors such as North Korea and Iran. Indeed, one of the justifications for launching the Iraq War was to prevent Saddam Hussein from acquiring a nuclear capability.

As a result, thinking about nuclear strategy and force structure atrophied. This can be seen by examining the evolution of the periodic Nuclear Posture Review process, begun during the Clinton administration in order to provide a comprehensive account of U.S. nuclear policy, including the role of nuclear weapons, nuclear force structure, and nuclear force options. For instance, the 2010 Obama NPR said that although Russia remained a nuclear peer, “Russia and the United States are no longer adversaries, and prospects for military confrontation have declined dramatically.” The Trump NPR attempted to reinvigorate U.S. nuclear weapons policy and strategy, especially in light of the reemergence of great power confrontation and Russia’s nuclear modernization.

NPRs were normally issued by the Department of Defense as stand-alone documents every five to 10 years, but in 2022, the Biden administration folded the NPR into the National Defense Strategy, stressing that the fundamental role of U.S. nuclear weapons is to deter nuclear attack on the U.S., its allies, and its partners. It further claimed that the U.S. would only consider the use of nuclear weapons in extreme circumstances to defend the vital interests of the U.S. or its allies and partners. What does all of this mean in light of the Russian invasion of Ukraine?

According to the Arms Control Association, currently deployed U.S. and Russian warheads for strategic weapons are about equal in number: 1,458 warheads on 527 intercontinental ballistic missiles, submarine-launched missiles, and bombers for Russia and 1,389 warheads on 665 intercontinental ballistic missiles, submarine-launched missiles, and bombers for the U.S. Both sides have more warheads in storage. No other country possesses anything near these numbers.

A major development in the evolution of nuclear strategy has been the vast improvements in the accuracy of nuclear delivery systems. For instance, satellite-linked guidance systems make it possible to deliver a warhead much closer to a target than in the past. This means that even strategic nuclear weapons now feature reduced yields because of the cubic relationship between accuracy and effect: Doubling the accuracy of a weapon is equivalent to increasing the yield eightfold. And herein lies the first paradox.

Arguably, nuclear states have avoided crossing the nuclear threshold because of the immense destructive power of thermonuclear weapons. But improved accuracy means that a more accurately delivered weapon requires a much smaller yield, compared to a less accurately delivered warhead, to achieve the same effect on the target, producing the necessary overpressures to destroy even hardened targets while reducing collateral damage. Ironically, this theoretically removes an obstacle to the use of nuclear weapons, which has led some observers to express concern that increased accuracy means that nuclear weapons have become more “usable.”

Given this reality, would Russia consider using tactical nuclear weapons within Ukraine to break the current stalemate, risking escalation? On the one hand, the Russians have apparently developed very low-yield nuclear warheads that can be delivered by air or short-range ballistic missiles. Of most concern is the Iskander-M (NATO designation SS-26 Stone), which has already been employed extensively to deliver non-nuclear explosives.

On the other hand, we face a second paradox. Both the U.S. and Russia have developed non-nuclear warheads that produce blast effects and overpressures similar to those of a small nuclear weapon, such as thermobaric weapons. The Russians no doubt also have munitions such as the U.S. Massive Ordnance Air Blast bomb, which was used against an Islamic State tunnel complex in Afghanistan in 2017. The latter contains some 18,000 pounds of an ammonium nitrate/powdered aluminum gelled slurry detonated by a high explosive booster.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Russia also possesses a non-nuclear electromagnetic pulse warhead capable of knocking out communications and modern electronics in a broad area. Such a specialized Iskander radio frequency warhead delivered by an Iskander-M would affect electronics and communications within a radius of some 10 kilometers from the detonation point.

So the two paradoxes of today’s nuclear weapons are that (1) technology, primarily improvements in accuracy, has made it possible to reduce the explosive power of nuclear weapons, arguably making nuclear weapons more usable, and (2) other technological advances have caused the effects of nuclear and non-nuclear weapons to converge. While the first paradox would seem to make a nuclear confrontation more likely, the second paradox makes it less likely that either Russia or the U.S. will cross the nuclear Rubicon in Ukraine.

Mackubin Owens is a senior fellow of the Foreign Policy Research Institute and a national security fellow at the Clements Center for National Security at the University of Texas, Austin.