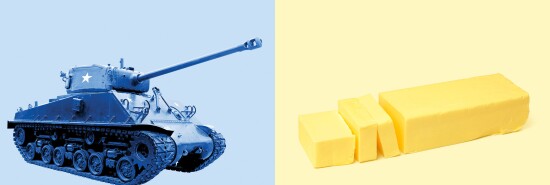

Guns vs. butter

Mackubin Owens

Video Embed

“Guns vs. butter” has been a perennial feature of standard macroeconomics textbooks for decades. The phrase purports to illustrate the concept of “opportunity cost,” which economists define as the highest-valued alternative foregone by choosing one course of action over another. It is a simple way of showing that given a finite stock of resources represented by a “production possibilities curve,” one must make trade-offs. By consuming more of one good, a decision-maker can consume less of another. The highest-valued good that is given up is the opportunity cost.

The guns vs. butter concept has long been a staple of electoral politics as well. Do we need to spend more on defense? If so, what is the opportunity cost in terms of social goods foregone (in other words, the “butter”)? The term gained prominence during the presidency of Lyndon Johnson when his administration confronted the challenge of funding his “Great Society” programs while conducting the Cold War in general and the Vietnam War in particular.

The idea of guns vs. butter was graphically described by President Dwight Eisenhower in his 1953 Chance for Peace speech: “Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed. This world in arms is not spending money alone. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children.”

Its most recent iteration, of course, is the debate over support for Ukraine. Over the past year, the United States has provided nearly $47 billion in military assistance to Kyiv. President Volodymyr Zelensky has continually asked for more, and indeed, some are inclined to issue him a blank check. But what is the opportunity cost of that aid? Opponents of a blank check to Ukraine point to the recent train derailment in East Palestine, Ohio, to argue that the funds that go to Ukraine might be put to better use in upgrading our own transportation infrastructure.

Of course, the issue is much more complex than a simple trade-off between spending on national security and domestic needs. For one thing, as a nation, we long ago chose to prioritize social spending over national security at the federal level. The federal budget comprises three categories: 1) nondiscretionary spending, which includes entitlements such as Social Security and Medicare, 2) discretionary spending, which includes defense spending, and 3) interest on the national debt.

The first category is not appropriated by Congress. By law, anyone who meets the criteria established by the legislation is entitled to the benefit. This category accounts for about two-thirds of federal spending. The second category must be authorized and appropriated on an annual basis and accounts for about a third of the federal budget. Interest on the debt accounts for about 10%. While defense accounts for around 60% of discretionary spending, it is still far less than what the government spends on entitlements.

The real trade-offs between defense and nondefense spending take place within the category of discretionary spending. Other components of this category include education, housing, transportation, and veterans’ benefits. Thus, arguably a dollar spent on defense comes at the expense of education. Of course, there are legitimate questions about whether the federal government should be spending funds on education and housing, expenditures that were once regarded as the responsibility of the states. The Constitution obligates the national government to “provide for the common defense.” There is no mention of providing funds for housing and education.

The real opportunity cost of military assistance to Ukraine does not exist in the area of domestic spending but in other areas of military spending. By supplying weapon systems to Ukraine, we have depleted our own stockpiles of weapons, such as the High Mobility Artillery Rocket System and air defense systems. This has created problems for the U.S., especially in the Indo-Pacific region, where we face our primary strategic challenge from China. For example, the Japanese newspaper Nikkei reported in early October that some parts of planned joint drills between Japan’s ground forces and U.S. Marines were canceled due to a lack of shells for the HIMARS launching systems. Some defense analysts argue that President Joe Biden’s most recent defense budget does not spend enough on the Indo-Pacific region in light of the challenge posed by China.

In the end, the decision to provide military assistance to Ukraine must be based on sound strategic thinking. But debates over more aid to Ukraine all too often lack a coherent strategic context. At a minimum, such a coherent strategic vision would couch the debate over more aid in terms of U.S. interests in Ukraine and how they relate to broader global U.S. interests, especially in the Indo-Pacific region.

But U.S. policymakers have repeatedly failed to articulate our strategic objectives in Ukraine. At the outset, defense of the U.N. Charter and democracy seemed to be the primary goals. The objective appeared to be limited, a negotiated peace that ended the carnage. But lately, a “Ukraine victory coalition” that seeks to weaken Russia permanently has become dominant in Washington. It is this coalition that seeks a blank check for Ukraine, apparently without regard to the costs and risks associated with such a strategic goal.

Those risks are substantial: a possible direct confrontation between Russia and the U.S. and NATO, the creation of a dangerous anti-U.S. alliance that not only forges deeper ties between Russia and China but also includes a number of other states, such as India, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Iran, and financial problems associated with increased inflationary pressures.

Although Ukraine has the right to appeal to the U.S. for assistance in repelling Russian aggression, American citizens have a legitimate expectation that Ukrainian interests do not come at the expense of U.S. interests. Giving Ukraine a blank check, as some wish us to do, is the very opposite of a prudent U.S. foreign policy.

“Guns vs. butter” has an emotional appeal, but assistance to Ukraine must be examined in the cold light of sound strategic reasoning.

Mackubin Owens is a senior fellow of the Foreign Policy Research Institute and a national security fellow at the Clements Center for National Security at the University of Texas, Austin.