White Noise is a sentimental farce

Hannah Rowan

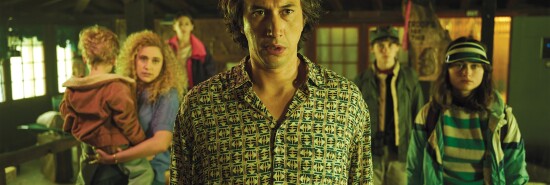

Video Embed

Noah Baumbach once said that in directing Frances Ha, his goal was to “make big moments out of little ones.” This is a perfect distillation of his films, and it makes him uniquely ill-suited to adapt Don DeLillo’s 1985 novel, White Noise, for the screen. Baumbach turns DeLillo’s black comedy about the fear of death into a sentimental farce.

The film version of White Noise, newly released on Netflix, doesn’t take long to reveal this point, though it spends plenty of time, well over two hours, repeating it. The story goes like this: Jack Gladney (Adam Driver) is a professor of Hitler studies who doesn’t speak German. This makes him insecure and also obsessed with, and terrified of, death.

AMERICA’S STRUNG-OUT ZEITGEIST HAUNTS THE VENICE FILM FESTIVAL

When a train crash releases a cloud of toxic waste, he and his wife (his fourth) and his four children (most from different marriages) have to evacuate along with the residents of their Midwestern town. But carnage from Stephen King’s The Stand does not follow. The family returns home, and Gladney is informed that because of his exposure to the dangerous chemical, he will probably die. Sometime. Later — years or maybe decades from now.

As he agonizes over this prognosis, he learns that his wife, Babette (Greta Gerwig), has taken more drastic measures to escape her own fear of death, including being unfaithful to him. Gladney sets off to get revenge. He has to decide, as his professor friend, Murray Jay Siskind (an Elvis expert played by Don Cheadle), puts it, whether he’s a “killer” or a “dier.”

As often happens in DeLillo’s stories, the results are mixed, as campily comical as they are sad. Gladney responds to the unreality of this bizarre sequence of events with what could be read as growing maturity, passive resignation, or simple incomprehension.

Why? Well, the miracle of the American supermarket, for one thing. More important to White Noise than its aborted dystopian plot are its commercial gathering places where characters go to decompress and make sense of their lives.

DeLillo is America’s great chronicler of conspicuous consumption: “Here we don’t die; we shop,” says Siskind. At the supermarket, Gladney’s family and colleagues do much more than buy groceries. They walk the aisles and are comforted. The brightness of the lights and packaging, the symmetry of the food displays, the impossible perfection of the produce, the cheerful closing transaction with the cashier — they’re all so satisfying, a validation of the knowledge that one is alive and the belief that one will continue to be so indefinitely and in as pristine a condition as the products on the shelves despite all the evidence to the contrary.

Shopping has religious overtones in White Noise but dark ones. DeLillo’s characters have to make sense of lives concocted from such colorful but synthetic ingredients. There’s a false taste to it all, from the dissipating toxic airborne event to the botched vendetta against the lecherous villain to the ultimate refuge taken among the rows of Doritos.

If DeLillo’s White Noise tastes artificial, Baumbach’s is saccharine. White Noise is Baumbach’s first film not based on a story he wrote, most of which are largely autobiographical, and it shows in its lapses into the earnestness of Frances Ha.

Baumbach allows the soundtrack (by Danny Elfman) to impose triteness on moments such as Jack’s reaction to Babette’s confession of her infidelity (sad piano and strings) and his decision to chase down the culprit (video game-style adventure music). It’s as if the confusion caused by the materialist characters’ inability to make sense of their lives could be relieved by simply letting a bit of true feeling shine through.

Worse, he moralizes. In a crucial scene, a nun berates Gladney for his naive belief that because of her vocation, she believes in God, and Baumbach inserts this humanist drivel as her parting shot: “So maybe you should try to believe in each other.”

Worst, Baumbach’s White Noise ends happily. In the final scene, the Gladney family returns to the supermarket. As the glass doors slide open, Gladney delivers the film’s last lines, partly lifted from DeLillo’s closing paragraph: “Out of some persistent sense of large-scale ruin, we keep inventing hope. And this is where we wait. Together.”

Then they dance. Credits roll over what becomes a music video for LCD Soundsystem’s “New Body Rhumba,” the band’s first release in five years, produced just for the film. The family twirls around waving boxes of Lucky Charms and bottles of mustard, and the other customers join in, united in their orgy of self-conscious consumerism.

There is nothing quite so cute in the final line of the book. DeLillo’s last word from the supermarket is withering: “Everything we need that is not food or love is here in the tabloid racks,” including “the cults of the famous and the dead.”

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Hannah Rowan is managing editor of the American Spectator.