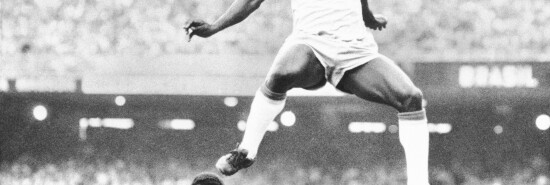

Pele, architect of the beautiful game

Dominic Green

Soccer was not born as “the beautiful game.” It was made beautiful by the artistry of its best players. Nor was soccer born as a global game. It became global in the 1950s through television. No one played the game more beautifully than Pele, the Brazilian soccer player who died on Dec. 29 at the age of 82. The supreme artist of the round ball, he became the first global sports star.

Every nation honors the memory of its best players. All of them cherish the memory of Pele. No other player exists in the soccer empyrean beyond partisanship or debate. This is not just because Pele is the only player to have won three World Cups. In Pele, we saw soccer’s Platonic ideal, mind and body beyond the merely human, perfection in motion.

The son of a professional soccer player, Edson Arantes do Nascimento was born in 1940 in Minas Gerais state (“Edson” was his parents’ misspelling of “Edison,” as in lightbulb; “Pele” his mispronunciation of “Bilé,” the nickname of his local team’s goalkeeper). He grew up in poverty, playing with a sock stuffed with paper and tied with string and working as a servant in tea shops. After playing in the first team to win the national futsal (indoor soccer) championships, he turned professional at 15 with Santos FC. The top scorer in the 1957 Brazilian league, Pele joined the national team for the 1958 World Cup in Sweden as a center-forward.

Pele was the tournament’s youngest player and its star performer. The prodigy had the speed and power of a classic center-forward. Unusually, he kicked equally well with both feet and excelled at heading even though he was 5 feet, 8 inches tall. Rarer still, he was an intuitive reader of the game, with a fencer’s spring-heeled grace and a chess player’s feel for the moves and passes. He scored twice in Brazil’s 5-2 rout of Sweden in the final. The Swedish player Sigvard Parling later admitted, “When Pele scored the fifth goal in that final, I have to be honest and say I felt like applauding.”

In the 1962 finals in Chile, Pele scored in Brazil’s first game but was injured in the second. Brazil, whose style now elevated soccer into a more complex and skillful game, went on to win regardless. They would have won the 1966 tournament in England, too, had they not been fouled out of the group stages by a thuggish Portugal.

The team that Brazil sent to the 1970 finals in Mexico was the greatest in soccer history, and Pele was its chief ornament. At 30, he had matured into a playmaker, drifting wide to set up other scorers, dropping back to set the rhythm and control the pace. His surfeit of talent gave his play a comical impertinence, and the biggest of stages brought it out. In a group game, he tried lobbing the Czechoslovakian goalkeeper from the halfway line. In the semifinal against Uruguay, he broke through, sent the goalkeeper diving left, the wrong way, by pretending to kick the ball, then ran around the keeper’s right to collect the ball, shooting just wide of the far post.

The 1970 final remains the best. Brazil beat Italy 4-1. Pele scored the first goal and set up two more. The final was transmitted in color. Brazil’s multiracial team, their fluid, intelligent play, the green and gold of their strip, the thunder of the samba drums from stands, and Pele’s black skin were a vision as suggestive of human possibility as Brazil’s final goal. As the attack builds up, eight of the 10 outfield players pass the ball until Pele, anticipating Carlos Alberto’s run from deep, strokes it diagonally into empty space. You know Alberto will connect and score. The team’s rhythm is irresistible, and Pele’s touch has the grace of a mathematical theorem. Brazil, having won three times, got to keep the trophy.

In 1975, Pele semiretired to the New York Cosmos, developing soccer’s new frontier in the United States. Two years later, he played his last game, a Cosmos-Santos exhibition match at Giants Stadium. Life is a game of two halves. For sportsmen and women, the second half is much longer. Retirement brings a loss of status and stimulus, and the ego is primed for pitfalls. Pele seemed no less generous in his second-half career as the first sporting “ambassador,” endlessly shaking hands and posing for photographs, deliberately embodying the sporting virtues of excellence and restraint even as he suffered decades of pain from his crumbling hip joints.

Sport sublimates aggression for the good of all, so we convince ourselves that sport is about winning at all costs. Pele revealed the Corinthian principle that playing the game is what counts. The more artful the performance, the more therapeutic the ritual. Watch a clip of Pele pulling off some piece of magic, and you laugh. It was a joy to watch him.