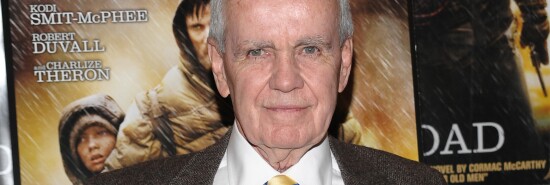

The double-barreled Cormac McCarthy

Gustav Jönsson

Fully 16 years after The Road, an 89-year-old Cormac McCarthy has published two new companion novels, likely to be his last, in two months: The Passenger and Stella Maris. The very first sentence of The Passenger tells us that McCarthy is back: “It had snowed lightly in the night and her frozen hair was gold and crystalline and her eyes were frozen cold and hard as stone.” Death comes packaged in one of those commaless, conveyor-belt sentences. It is very much trademark McCarthy. But the register isn’t that of Blood Meridian or No Country for Old Men. In those previous works, there were beheadings, castrations, lynchings. In his new novels, characters die in seemlier ways: either offstage or in the silent, snow-covered woods. Has McCarthy gone soft in old age?

Not really, only less gory. Which isn’t the same thing. These books have no roving bands of cannibals (as in The Road) or hellish scalp-hunters (as in Blood Meridian). But if there is less bloodshed, there is more existential woe. The Passenger came out first. Its protagonist, Bobby Western, “looked at the meatcleaver lying on the table beside his plate … Could you bury that in someone’s skull? Sure. Why not?” In McCarthy’s earlier novels, one could be sure that if a meat cleaver lay on the table, like Chekhov’s gun, it would (in the hand of a 7-foot-tall psycho) bifurcate someone’s head sooner or later. But now, it stays unbloodied.

The Passenger has some plot, but it peters out halfway through. Bobby’s backstory is this: He dropped out of Caltech because (unlike Alicia) he wasn’t clever enough to revolutionize physics or mathematics. He goes to Europe to compete in Formula 2, but it lands him in a coma. When The Passenger begins, he works as a salvage diver based in New Orleans. Diving to a crashed plane, he becomes suspicious that someone has tampered with the scene. Moreover, a passenger on the manifest is missing. Bobby is soon pursued by federal agents “dressed like Mormon missionaries” who (for unstated reasons) persecute him — the IRS closes his bank account and seizes his car. The plot is pretty thin, but it serves its purpose: Bobby, like so many other McCarthy heroes, must live hermitlike, as though he were the “last of all men” standing “alone in the universe while it darkens about him.”

The characters spend endless hours contemplating the meaninglessness of life. Kurt Vonnegut said that most lives aren’t worth living. Alicia, Bobby’s genius sister, has similar thoughts. Before killing herself, she lets it be known that she “wanted not to have been.” Bobby, who emerges from a car crash-induced coma only to learn of Alicia’s suicide, reflects that it would have been better if he hadn’t woken up. “I think a lot of people would elect to be dead if they didn’t have to die,” he says. Perhaps one can’t escape such gloom if one thinks of oneself in Bobby’s grandiose terms: “Western fully understood that he owed his existence to Adolf Hitler. That the forces of history which had ushered his troubled life into the tapestry were those of Auschwitz and Hiroshima, the sister events that sealed forever the fate of the West.” Bobby and Alicia’s father worked with Oppenheimer on the Manhattan Project. Now, therefore, “history is a rehearsal for its own extinction.”

McCarthy has never been strong on plot. Strictly speaking, the second of the twin novels to come out and the first chronologically, Stella Maris, has none. Set in 1972, eight years before The Passenger, it consists entirely of Alicia’s conversations with Dr. Cohen of Stella Maris Psychiatric Institute, where she has had herself checked in following Bobby’s crash. She has two problems: First, she has elaborate talks with hallucinated personages. Second, she suffers from a broken heart. She is in love with her brother Bobby, who is (seemingly forever) comatose in Europe. Though her love is requited, she regrets that it isn’t consummated. Now, instead of Bobby, she has “the Kid,” her hallucinated companion, with seallike flippers for hands and, in one of McCarthy’s perfect similes, a scarred face as though “he’d been brought into the world with icetongs.” The Kid speaks whimsically, a testament to McCarthy’s subtlety with unsubtlety. The Kid’s sentences are full of cliches: “cat got your tongue,” “will come out in the wash,” “knickers in a twist,” etc. The thoughtless language reveals him to be what he is: the product of schizophrenia.

There are two stylistic streams in McCarthy’s prose: the sparse running parallel with the vatic. Both can be found in his new novels. Here’s McCarthy as a literary pufferfish, his rhetoric fustian: “God’s own mudlark trudging cloaked and muttering the barren selvage of some desolation where the cold sidereal sea breaks and seethes and the storms howl in the form out of that black and heaving alcahest.” And: “In that dusky penetralium they press about the crucible shoving and gibbering while the deep heresiarch dark in his folded cloak urges them on in their efforts.” This could fit right into the portentous narration of a third-rate fantasy story. It is pseudo-Biblical in its bloat, but it occasionally results in felicitous phrases: the mule stands “footed,” the “flames sawed in the wind.”

McCarthy de-puffs, too: “He leaned and opened the glovebox and took out a package of crackers and tore it open with his teeth and sat eating the crackers and waiting for the engine to warm.” There’s a lot of lumber here, page after page of it. The sentences hit like rain on a windscreen, leaving no impressions.

McCarthy has sometimes struggled to keep his characters within proper bounds. Bobby and Alicia feel rather fanciful. Bobby is the kind of tortured man that every woman longs to save. More than save, even. One of the early scenes has a woman, with “hungry” eyes, admire his plump ass. Bobby, chastely loving his sister, is of course immune to vixen charms. There’s nothing he hasn’t mastered. He plays the mandolin in a professional bluegrass band. When a friend of his quotes Emil Cioran, he replies with an apposite quote of Plato’s. He drives a 1973 Maserati Bora and recognizes at a glance a Patek Philippe Calatrava as a pre-War. James Bond would’ve envied Bobby. Still, he is good, but not unrivaled, in physics, and he never made it to Formula 1.

Alicia, though, is incomparable. After graduating from the University of Chicago at 16, she goes to work with Alexander Grothendieck at the Institut des Hautes Etudes Scientifiques. She reads five books a day and speaks a number of languages (no accent, naturally). She has perfect pitch and plays an Amati violin, though she gives it up when she realizes that she won’t be in the world’s top ten. She only bothers if she’s the very best. What’s more, she’s even more erudite than her brother: She riffs on Jung, Schopenhauer, Quine, Wittgenstein — there’s no one she hasn’t read. Intelligence is numerical, she says, though she has nonetheless memorized everyone from Montaigne to Chesterton. Though she works 18 hours a day, she has had time to commit Marlon Brando’s lines to memory. Need I mention that she is “drop dead gorgeous”? McCarthy gives her schizophrenia like DC Comics gave Superman kryptonite — otherwise, she’d be too perfect.

The octogenarian McCarthy gives full rein to intellection. Genius is not so much praised as worshiped, but it feels second-hand. Robert Musil said that the problem with The Magic Mountain was that Thomas Mann had, like a shark swallowing its food whole, gobbled up ideas without chewing them. Something similar could be said of the twin novels under review: McCarthy has crammed them with everything he knows and a lot he doesn’t. The result is a little unconvincing, but it isn’t without rewards. “Trimalchio is wiser than Hamlet,” says Bobby’s libertine friend Sheddan — that sounds like something a graduate student, eager to impress, might say at a party (there he is, practicing the line in front of the mirror, imagining that particularly cute classicist beaming with admiration). But sometimes, it is rather nice to be impressed.