Late Night has lost its joy

Peter Tonguette

In many ways, the world as it was in 2007 is quite remote from the present moment.

Back then, George W. Bush was the Republican standard-bearer derided by the Left, while Donald Trump was likelier to pick a fight with Rosie O’Donnell than anyone in Washington. And when you think back to the various celebrity scandals, indulgences, and excesses of 1 1/2 decades ago — say, the untimely death of Anna Nicole Smith or the fleeting incarceration of Paris Hilton — they can seem as distant as a dream.

Yet at least one episode from 2007 still resonates, both as a reflection of that time and a lens through which to view our own. In February 2007, pop icon Britney Spears accelerated her transition from musical stardom to troubled celebrity du jour with a one-weekend crack-up that included a single-day stop at a drug rehabilitation clinic and the shaving of her head.

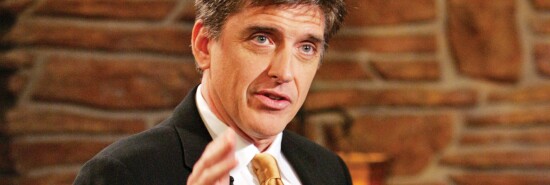

Spears’s actions in and of themselves aren’t worth remembering as much as one man’s unusually good-natured and merciful reaction to it: On Feb. 19, 2007, amid the Spears imbroglio, Scottish comedian Craig Ferguson, then installed as the host of The Late Late Show on CBS, stood before his audience and said a word in defense of the troubled singer. As Spears continues to make news with her often inexplicable behavior, and as countless other celebrities, public officials, and politicians make ever easier targets for our contempt, Ferguson’s spirit of generosity might serve as a guide.

Naturally, Ferguson, one of the most dryly amusing of all late-night hosts, was funny in much of what he said, but he was really trying to open hearts. Launching into the sort of lengthy, unpretentiously philosophical opening for which he was already famous, Ferguson characterized what he was about to say as a mea culpa. Yet that term suggests an isolated act for which one admits culpability. No, Ferguson was calling into question the entire business of using celebrities as human pinatas.

Ferguson began by describing his unexpected reaction to running into Kevin Costner after roasting him on national TV. “I could see in his eyes he made a decision to not go after me, just to be polite and nice and stuff,” he said. “And it kind of freaked me out, it kind of personalized it for me.” Here, the host offered a welcome lesson: Celebrities, like all people, are capable of bleeding, and it may not always be worth pricking them when they are, like Costner, basically benign.

But then the monologue took a turn. When Ferguson admitted that he felt it was time to change course and there would therefore be “no Britney Spears jokes” that night, the studio audience tittered. Ferguson could not resist cracking a smile along with his crowd, but he was serious. As he saw it, Spears was someone in trouble, and those who made a national joke out of her should think twice.

Then the monologue went to an even deeper place. Ferguson noted that, on the weekend of Spears’s breakdown, he had been sober for 15 years. Her situation, he said, reminded him of his life prior to sobriety. Over the next 10 minutes, Ferguson recounted his own troubles with alcohol, including the low point, at age 29, of waking up on Christmas and deciding that he should jump to his death from Tower Bridge in London. Only the offer of a glass of sherry from a bartender prevented him from following through. “One thing led to another, and I forgot to kill myself that day,” he said. Within a few months, he had sought help, but he made clear that his struggle was ongoing, continuous, without end.

It’s no surprise that the studio audience listened with rapt attention — they were present, after all, because they liked Ferguson — but the host drove home his original point: If you feel sorry for me, have a little sympathy for Britney. “This woman has two kids. She is 25 years old — she’s a baby herself,” he said. “The thing is, you can embarrass somebody to death. It’s embarrassing to admit you’re an alcoholic.” And he was getting out of the embarrassment business.

What to take from this extraordinary act of empathy in the annals of popular culture? First, Ferguson was surprised to be here to tell his own tale. Second, that such a realization should leave one in a state of joy, and one so full of joy should do better than tell stale, mean-spirited Britney jokes. Ferguson is the only late-night host capable of giving such a candid, earnest, and self-critical monologue.

Yet it’s hard to overstate Ferguson’s dark horse status when CBS was mulling who would assume the seat of Craig Kilborn, the ex-Daily Show host who had brought a kind of blond-haired, blue-eyed frat-boy insolence to The Late Late Show.

At the turn of the millennium, Ferguson had achieved some fame for his supporting part on The Drew Carey Show. No one reckoned, though, that he was the next Jack Paar. Mostly, he tossed around on television and in low-budget feature films. So, his 2005 appointment to the show was greeted with something of a shrug, including, apparently, by the host himself. “I think that if there’s a reason I got this job, it’s because I really didn’t try,” Ferguson told the New York Post upon getting the gig after a seven-episode tryout process.

Not having ever anticipated sitting at the helm of a late-night desk, Ferguson approached his job with the sort of casual abandon of one who, some years earlier, might not have anticipated even being alive to seize an opportunity. Watched again today, Ferguson’s Late Late Show is suffused with a devil-may-care-ism that separates itself from nearly all comparable programs, past and present.

Yes, all post-Letterman late-night hosts have gimmicks and recurring segments, but have there ever been two sidekicks as enjoyably, even pointlessly goofy as Ferguson’s gay robot, Geoff, or his equine puppet, Secretariat? When Ferguson interviewed his guests, one had the impression that he was neither poking at them, like Letterman, nor in awe of them, like Leno, but engaged in actual dialogue with them. When he laughed, one had the sense that he really found something funny, and when he flirted, as he did often with the numerous comely actresses who sidled up beside him, one had the sense that he really found this person fetching.

Once, Ferguson greeted actress Miranda Kerr by saying she looked “absolutely lovely, like, really very nice indeed.” Kerr retorted, “And you’re very handsome, too,” and when Ferguson asked for a bit more oomph from her compliment, she complied, with a wink: “I think that we should take our kids on a play date together.” We must admit that this kind of healthy give-and-take between the sexes was enjoyed both by the participants and those watching at home, as it would be today, if we could get over our #MeToo-era neuroses. At his best, Ferguson was a purveyor of glad tidings and good times.

Then, of course, there were the monologues. If the Spears monologue was a confessional high point for Ferguson, it was far from his only heart-to-heart moment. His astonishing eulogies for his father and then his mother were shot through with sentiment, pain, and seemingly stream-of-consciousness memories. He described his mother as an open, inquisitive soul who chose to become a teacher on the heels of raising four children, coaxed her recalcitrant husband, Craig’s father, into participating in an amateur operatic production, and became an artist late in life, painting a sparrow that, Ferguson said, was so mean-looking that it would have startled Alfred Hitchcock. When Ferguson’s voice cracks near the end, it’s agonizingly genuine.

In 2014, Ferguson departed The Late Late Show, and though he remains a public figure thanks to hosting duties on this or that game show, his cheerful nonchalance and emotional openness are entirely distinct from the likes of Jimmy Fallon, Jimmy Kimmel, and Stephen Colbert. Those hosts may think they are pushing boundaries, but they scribble within the margins of what their liberal, cynical, increasingly woke audience will tolerate. Forget late-night TV: We have entered a glum, joyless period — one in which Ferguson’s freestyling joie de vivre would seem more out of place than ever.

Those of us nostalgic for the old days increasingly turn to anti-woke figures such as Dave Chappelle and Bill Maher, but we may be erring in hitching our wagon to such divisive figures. Mean-spirited puritanism should be answered by something more lasting than equally mean-spirited shock jock-ism. The better antidote is found in Ferguson, whose personal history, so hauntingly sketched in the Spears monologue, gives him a perspective on life worth emulating. Every moment is precious, and the more that are filled with genuine laughs, and absent pettiness and vindictiveness, the better. “My job here is to try and give you a laugh or something interesting at the end of a day, something to entertain you or something a bit silly,” Ferguson said in a monologue addressing the 2012 movie theater shooting in Aurora, Colorado, another monologue in which he did more than just that.

If Ferguson’s plea for sympathy for Spears was unusual in 2007, it is downright countercultural in 2022. The same enmity that inspired an earlier generation to mock Spears is at work each time someone sends out a needlessly vicious tweet, wishes for the prosecution of a political foe, or indulges in schadenfreude when a celebrity crashes and burns. Let us remind ourselves of the wisdom of that funny and kind Scot who, for nearly a decade, found himself at the top of the talk show heap and helped make more humane all of us watching along at home. Let’s listen to Craig: Be more like Kevin Costner, polite and nice and stuff.

Peter Tonguette is a contributing writer to the Washington Examiner magazine.