The guarded John le Carré

Andrew Bernard

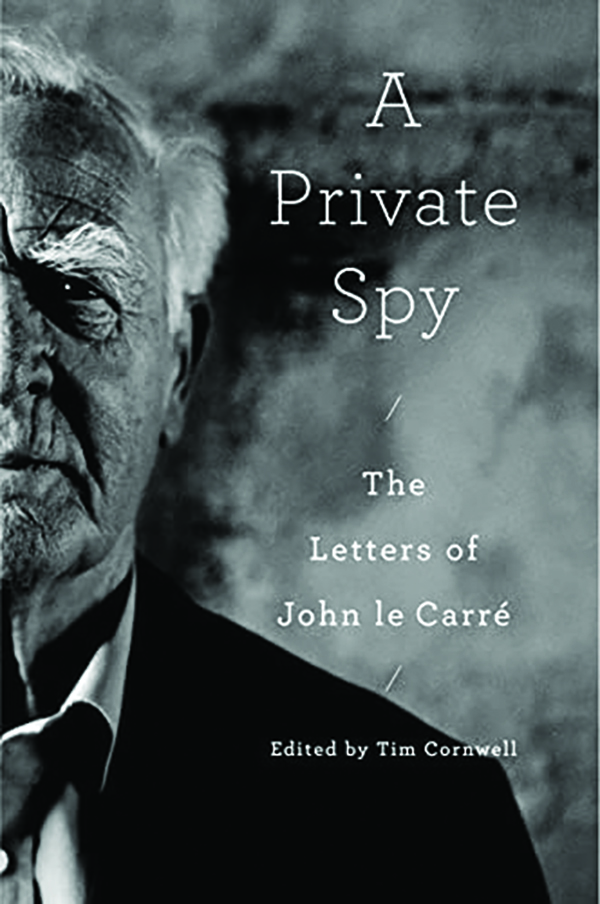

The joy in a book of letters is to see an author unguarded, unedited, and unrestrained. But most authors are not the beneficiaries of MI6 training. Unfortunately for the reader of A Private Spy: The Letters of John le Carre, the writer has largely covered his tracks.

David Cornwell, the real name of the man whose pen name was le Carre, admitted destroying correspondence with some of his closest associates. And he wrote, as early as 1961, the year his first novel was published, that he intended to “cultivate” his letters for future biographers. Here, the biographer on the trail is his own son, Tim Cornwell, who edited the volume and who died of an embolism shortly before publication. In this collection of letters, we mainly get the writer as he meant himself to be presented to the public, with mere hints at his marital infidelities, maddeningly small clues about his real-life spy work, and a single surviving letter to his conman father.

Where some sons might try to conceal their father’s secrets further, Cornwell’s invaluable footnotes and contextual introductions help to separate the “gold dust” from the “chicken feed,” to use le Carre’s jargon. What we’re left with is the portrait of a consummately polite workaholic with a complicated but seemingly loving adult family life.

His literary legacy is immense and impressive. In his six-decade career, le Carre published 25 novels, with a 26th published posthumously. At the time of his death, the only living writers whose work had been adapted to the screen more times than him were Stephen King and Nicholas Sparks. The letters suggest he went to the grave working on more material about his best-known hero, George Smiley, most famously the hero of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, adapted both into a BBC serial starring Alec Guinness and a 2011 film starring Gary Oldman and Colin Firth.

His political legacy is colored by how he achieved his more “realistic,” ambiguous Cold War fiction. One of the most interesting letters in A Private Spy is le Carre’s 1966 open letter to the KGB-controlled Soviet Literary Gazette, in which he describes how in his first bestseller, The Spy Who Came In From the Cold, he has “equated” East and West to bring out the similarities in their conduct. ”I sought to remove espionage from the sterile arguments of the cold war and concentrate the reader’s eye on the cost to the West, in moral terms, of fighting the legitimised weapons of Communism,” le Carre writes. “For this reason, my Western agent is at a loss to defend himself in ideological dispute with his Communist interrogator.”

His point was that communism was better equipped to make the choices that spycraft demands: morally compromised ones. Or, at least, that Western spies and Western readers have a need to lie to themselves about it:

“In espionage as I have depicted it, Western man sacrifices the individual to defend the individual’s right against the collective. That is Western hypocrisy, and I condemned it because I felt it took us too far into the Communist evaluation of the individual’s place in society.”

Le Carre was, in short, trying in his books to weigh Western hypocrisy against Eastern totalitarianism. While he was always clear that the balance tipped in favor of the West, this ambivalence caused him to create more nuanced literary depictions on the one hand and to reach staggeringly false moral equivalencies on the other.

Of the Salman Rushdie affair, in 1989, he wrote to the Guardian that “anybody who is familiar with Muslims, even if he has not had the advantage of Rushdie’s background, knows that, even among the most relaxed, you make light of the Book at your peril. I don’t think there is anything to deplore in religious fervour. American presidents profess to it almost as a ritual, we respect it in Christians and Jews.” Four years later, le Carre would write privately to a journalist that he was “taking on the Rushdie Thought Police” — a perverse way to describe supporters of a man living under the ayatollah’s perpetual death sentence. Rushdie and le Carre settled their differences in 2012.

Le Carre’s politics become more frequent and more tedious in the letters that appear after the year 2000, which make up the final third of the book. It’s difficult to begrudge a man in his 80s with cancer a bad opinion or three, but his conclusion in a 2020 letter to Daniel Ellsberg that “Snowden is a loyal American” is a lot to take from a man whose career in espionage and as a novelist was defined by close examinations of traitors.

More interesting is le Carre’s late-life friendship with playwright Tom Stoppard, in which the two trade notes as professional equals and masters of their overlapping crafts.

Le Carre’s other literary relationships and influences recur throughout. Le Carre had a tempestuous relationship with Graham Greene, who helped launch the younger writer’s career when he provided a blurb for The Spy Who Came In From the Cold as “The best spy story I’ve ever read.” Their falling out might help explain le Carre’s later reluctance to provide reviews for the various spy novelists who solicited his support over the decades.

More surprising is the debt le Carre pays to P.G. Wodehouse, whom le Carre calls “the Master” of plot. In a letter to Wodehouse biographer Robert McCrum who observed that Wodehouse, in his novels, took refuge in an “Elysium of imagination,” le Carre wrote that he relied on the same defense mechanism. “The Spy stuff that I invented was also a paradise, if a pitch black one, and I find myself in age returning to it, or sticking with it, in blithe despair, as it all returns to me.”

Whether or not he meant his work to be a reply to fellow spy and espionage novelist Ian Fleming, le Carre’s Smiley served as a sort of anti-Bond. His Cold War was neither heroic nor glamorous, and as le Carre saw it, society as a whole was seedier, not sexier, because spies walk among us. Le Carre writes that Bond is “a hyena who stalks the capitalist deserts … he is a chauvinist, an unblinking patriot who makes espionage exciting. […] Above all, he has the one piece of equipment without which not even his formula would work: an entirely evil enemy.”

Kingsley Amis, who wrote a Bond sequel in 1968 after Fleming’s death, would later describe le Carre’s understanding of Bond as “bubbling dogsh*t,” le Carre as a “most frightful pisser,” and le Carre’s characters as “dull f***ers.” That’s unfair to le Carre’s excellent novels, but it is an unfortunately accurate description of le Carre’s letters, which will mostly be of interest to academics and any ardent completionists among his fans.

Andrew Bernard is the Washington correspondent for the Algemeiner.