“Who’s afraid of Virginia Woolf?,” the most famous rhetorical question in English, is now retired upon finding an answer: Francesca Peacock.

The reputation of Margaret Cavendish, the subject of Peacock’s debut book, was accustomed to attacks during and well after her lifetime. Her Restoration-era contemporaries deemed her unlearned and insane, and some denied her authorship altogether. Her works were often published with copious errors and gross misspellings, even by 17th-century standards, only to have Victorian “editors” correct them beyond recognition. But it was Virginia Woolf who rendered the final, devastating judgment. “What a vision of loneliness and riot the thought of Margaret Cavendish brings to mind,” she wrote in A Room of One’s Own, “as if some giant cucumber had spread itself over all the roses and carnations in the garden and choked them to death.” With some of the most colorful insults in criticism, Cavendish was deemed the Miss Havisham of English literature.

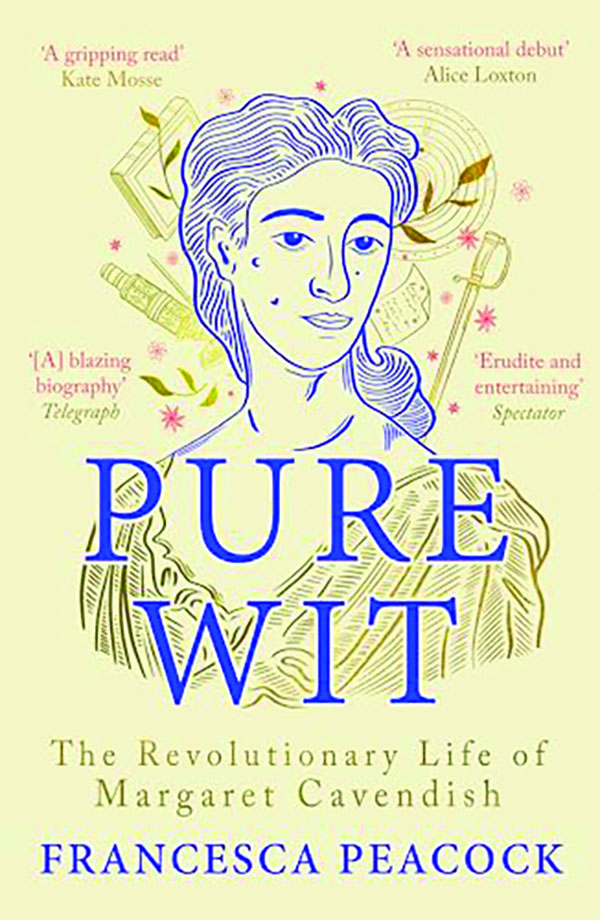

Woolf’s name and words appear often enough in Pure Wit as to turn the biography into an amicus brief for a Court of Appeal sometimes. This is not the only recent biography of Cavendish. She has inspired an independent film, a historical novel, and a work of contemporary fiction all in the last decade, to say nothing of her constant presence in academia. Her major works are still in print. All the same, Cavendish is continuously slighted by history, Peacock argues. Her “radical” contributions were dismissed even by feminists. (Germaine Greer called her “the crazy Duchess.”) It at least provides a locus for the reader as he or she progresses through Peacock’s recounting of a bafflingly contradictory personality, a writer who was as exhaustively productive as she was formally and thematically innovative and whose short life coincided with the most disruptive period of British history and was not immune to some of its harsher consequences.

For a single-volume popular biography, Pure Wit is a deft balancing of criticism, narrative, and historical exposition. Margaret Lucas Cavendish was born in 1623, and her life extends from the decline to the restoration of the House of Stuart. Violence and disruption were routine for her Royalist family during the civil war, losing lives and property to Parliamentarian retaliation. Though shy and melancholy by her own description, not to mention spottily educated, Cavendish was precocious and ambitious. At 19, she joined the court of Queen Henrietta Maria at Oxford. The austere atmosphere of court life was not to her temperament, and she satirized it in later work. Nevertheless, she followed the court to exile in France, where she met fellow Royalist William Cavendish, an intellectually inclined patron of the arts and a widower 30 years her senior, whom she would marry. Along with his brother Charles, William Cavendish would fill the gaps in Margaret’s learning, introduce her to the work of leading intellectuals of the age — Hobbes and Descartes were guests — and encourage her writing.

Peacock weaves a life driven by uncommon volatility, of natural intelligence and raw talent set up against social limitations, of isolation, and of sudden reversals of fortune. Yet her literary pursuits were enabled rather than stifled by the chaos. Cavendish’s work knew few limitations in terms of form or subject matter. She wrote verses, essays on a vast number of topics, and plays that defied the theatrical conventions of her day, and she defended literary lost causes (at the time, Shakespeare) and debated the work of contemporary philosophers, some of whom even replied.

Peacock highlights the many radical aspects of this output: her skepticism of witchcraft, the deployment of gender fluidity and same-sex love, and her scathing remarks on marriage and the culture of childbirth of the time. Though the radicalism is tempered by historical context. No time seems more alien to the 21st-century reader than 17th-century England and its violent, oft-forgotten revolution. Cross-dressing in drama was frequent. Women put themselves in as much danger as men during the civil war. The Anglican establishment was as much a hotbed of intellectual heresy as Milton and the Roundheads. Female writers became increasingly vocal.

Peacock upholds The Blazing World as Cavendish’s signature achievement. A mix of science fiction, philosophy, utopian feminism, satire, and even metafiction, the work was polarizing in her day. Many thought it chief evidence of her insanity, while her ridicule of the Royal Society’s scientific empiricism earned her an invitation to visit a meeting, the first for a woman. Today, the work has a serious claim alongside the classics of premodern postmodernism, such as Jonathan Swift’s A Tale of a Tub and Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy. Equally polarizing are her plays. In addition to being rife with biting observational satire, they famously disregard theatrical conventions. “Cavendish wrote texts more akin to a cacophonous episodic TV series, with subplots and simultaneous narrative arcs which seem to have nothing to do with each other.” Few, if any, were ever performed. “Without an atom of dramatic power,” Woolf wrote, the staging of her plays seemed “a miracle.”

So dedicated is Peacock to articulating Cavendish’s contradictory multitudes that the reader may have to make his or her own judgment as to her exact merits. Is she to be held up as misunderstood equal to her Restoration peers, even if her learning and style are idiosyncratic? Or is she the great feminist gadfly who saw far beyond her century? In both, she may fall short of the icons whose ambitions were more successful and accessible, such as Mary Shelley and the Brontës. Yet a more interesting dilemma arises on the particulars of her literary efforts.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

The last chapters of Pure Wit center on reassessing Cavendish’s reputation. Charges of immaturity, artlessness, and eccentricity followed her well after her death. If she weren’t Miss Havisham, she’d still be Henry Darger. While revision was an arbitrary tradition in her era, Cavendish often put out polished editions of her early work and could be incisive, as well as fanciful and spontaneous. Primed as Peacock wishes Cavendish to be for the canon (or something close enough), the zeitgeist in which she writes may still have other ideas about her subject’s work.

Cavendish’s spontaneous musings, her voracious curiosity, her anarchic imagination, her alternating boldness and self-consciousness, and even her bad spelling — all the things that marginalized her in centuries past, that is — are welcomed in the digital age. Margaret Cavendish may never be read on her own terms, no matter how much she or her modern advocates wish. Few authors ever are. But at least now Cavendish will be read, and somewhat more fairly.

Chris R. Morgan writes from New Jersey. His Twitter handle is @cr_morgan.