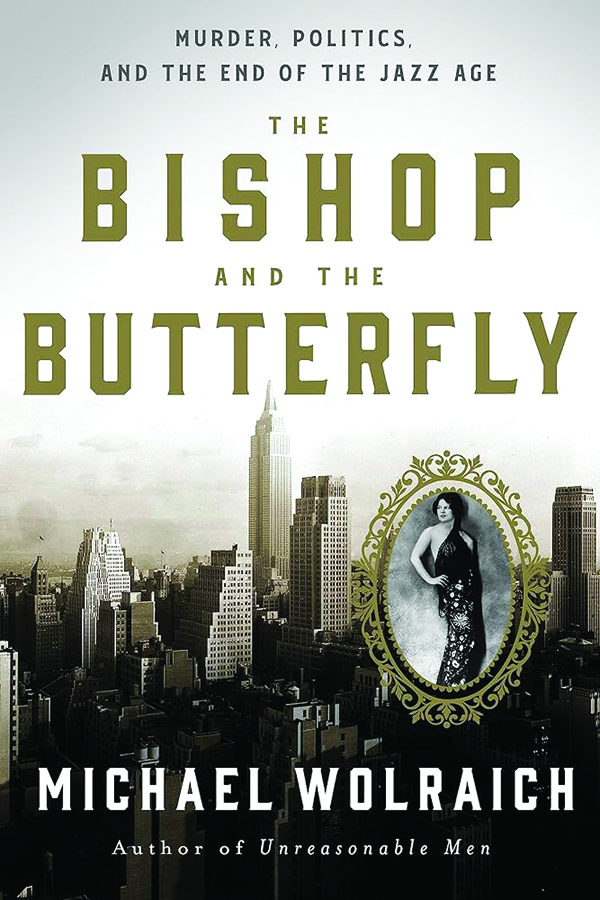

The Jazz Age may have ended in 1929, according to F. Scott Fitzgerald, who called it an age of miracles, an age of art, an age of excess — one that once people lost confidence, “it didn’t take long for the flimsy structure to settle earthward.” However, according to social historian Michael Wolraich, there was more going on during that era than a loss of confidence. Wolraich’s latest social history, The Bishop and the Butterfly: Murder, Politics, and the End of the Jazz Age, describes the period in extensive detail.

First, there was Prohibition, 1920 to 1933, which did not stop people from drinking. Rather, it motivated them to find illegal ways to partake. Then, and relatedly, there was crime: gin-filled bathtubs, bootleggers, speakeasies, and prostitutes. Above all, there was money, which passed from the lawbreakers to the corrupt police and politicians. Without money, one couldn’t have had the booze, sex, dancing, glamor, youth culture, or dreams.

Wolraich is the author of two earlier books, including the well-received Unreasonable Men, which focuses on the clash between President Theodore Roosevelt and House Speaker Joseph Cannon, depicting one representing conservatism and the other progressivism.

In this new book, Wolraich focuses on New York politics and corruption partly as seen through Franklin Delano Roosevelt, whose career and presidential hopes were inspired by his cousin, Theodore Roosevelt. In both books, Wolraich portrays Teddy and FDR during pivotal moments in their lives. Teddy, a Republican, needed to make peace with somewhat radical elements of his party. FDR, a Democrat, needed to clean up New York. Both books show how the two presidents succeeded.

Wolraich looks at New York City beginning with the late 19th century but focuses mainly on about two years, from 1929 to 1931, when Wall Street crashed, the Great Depression (1929-1939) took hold, and Vivian Gordon was murdered.

An enormous amount of money evaporated with the stock market crash of 1929. Beset with financial problems, New Yorkers could no longer tolerate the rampant corruption prevalent among the police, politicians, malefactors, and ordinary patriots.

The Bishop can be a bit hard to keep track of. It’s crammed with action, which seems to be Wolraich’s method: Pile on the details. Use lots of verbs, metaphors, and figures of sound. Take readers on a dizzying ride through New York City. Drop names. There are many to drop, perhaps too many, suggesting to me that this material should be covered in two books, not just one. The book features close to 90 dramatis personae — many of them villains with aliases.

Here are a few of the important players: Franklin Delano Roosevelt, New York governor; New York City Mayor Jimmy Walker, called the “night mayor,” a funny guy whom everyone loved because of his charismatic ways despite his graft-filled administration; Vivian Gordon, also known as Benita Franklin Bischoff, prostitute, madam, and extortionist; Benita Bischoff’s teenage daughter, who killed herself because she was depressed because of her mother’s death; Legs Diamond, Greenie, and Chowderhead Cohen, three of many underworld figures with colorful names; Polly Adler, madam and associate of Gordon; Samuel Leibowitz and John Radeloff, two sketchy lawyers; Harry Stein, a felon and strangler to whom Gordon loaned money for a bank heist in Norway but who never paid her back because the venture went awry; Harry Schlitten, chauffeur; Judge Samuel Seabury, a descendent of several Protestant bishops and one of the few honest men in New York; and Grace Robinson, a crime reporter for the New York Daily News who covered the Gordon story. One of a few women journalists, she would later be nominated for a Pulitzer Prize.

Wolraich offers several interlocking stories with subplots. A chronology would make the story easier to follow. The overall plot concerns FDR and whether he can add luster to his political image, which isn’t especially promising since he is crippled with childhood polio and tries to hide it by leaning on the arms of his assistants. But his major problem is that New York is a cesspool of iniquity, and this reflects badly on him and his governing capacities. How could he run the United States if he cannot even get a grip on New York State?

His antagonist is Tammany Hall, a Democratic political machine that was mostly responsible for New York’s wicked ways. It had strong ties to crooked lawmakers, organized crime, and various politicians. Tammany Hall controlled the Democratic Party’s nominations and the appointment of city officials. It had access to public money and profit-sharing operations. It influenced politics in New York City and New York State. In a sense, its power extended to the presidency of the U.S., for instance, when Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s plan to seek the presidency depended on wooing the approval of Mayor Walker with his Tammany Hall connections.

Roosevelt appointed Seabury (that is, referring back to the cast of characters, the honest judge) to clean up New York City and Tammany Hall. As Seabury and his assistants were investigating, they connected with Gordon, who promised evidence to reveal the criminal activities of some of her acquaintances to save herself from jail. She planned to meet with one of Seabury’s partners. Then, she was found strangled before the meeting was to occur. But she was organized and kept notes about her affairs, which included names, dates, and contact information. She was also an avid diarist and kept at least three diaries that listed events in her life, as well as thoughts about her associates, indicating, for example, that she thought one of her lovers might murder her. As prosecutors tried to find Gordon’s killer, they found these diaries, which provided clues to her murder.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

The climax of the story occurred in FDR’s office with a showdown between the honorable Samuel Seabury and the dishonorable Jimmy Walker. Their encounter, as Wolraich describes it, freed New York City from Tammany’s claws “and transformed it into the modern metropolis that we know today.”

Ultimately, this is an action-packed social history that nearly collapses under the weight of its details. Readers might become lost in the proceedings, but they’ll never be bored.

Diane Scharper is a poet and a critic. She teaches the memoir seminar for the Johns Hopkins University Osher program via Zoom.