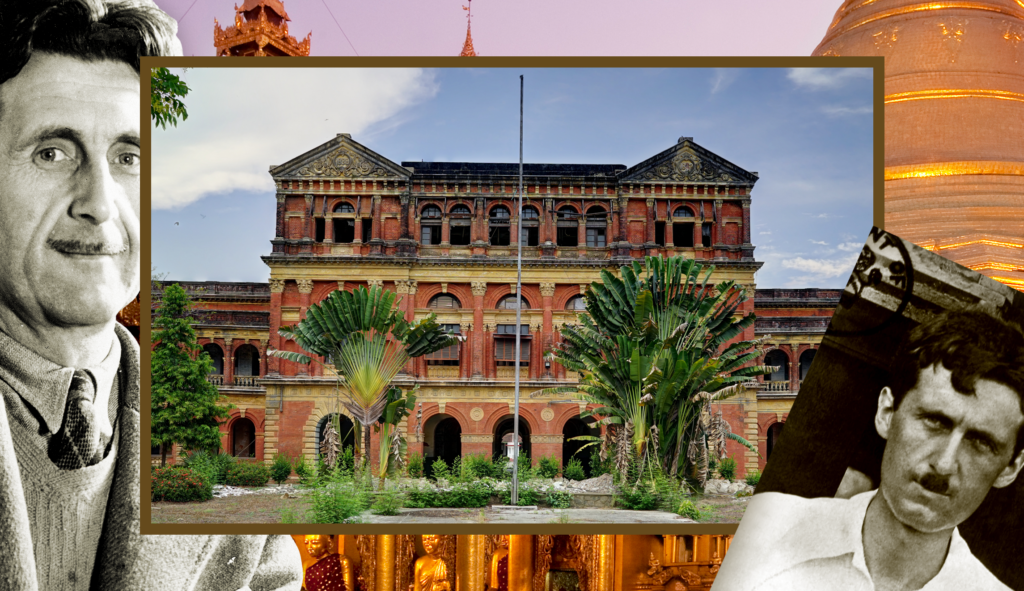

Seven decades on from his death, George Orwell is alive and well in publishing. Last year alone saw a slew of new releases about the man and his fictive worlds. There was Orwell: The New Life, a second and now definitive biography by Orwell authority D.J. Taylor. Masha Karp’s George Orwell and Russia explored the reception of his work in the Soviet Union, while Oliver Lewis’s The Orwell Tour retraced the peripatetic author’s steps. In her novel Julia, Sandra Newman reimagined 1984 from the viewpoint of Winston Smith’s tragic lover, and in her genre-defying book Wifedom, Anna Funder brought back into sharp focus Orwell’s first spouse, Eileen O’Shaughnessy.

400pp., $30.00

And then, there are the books by Orwell himself. Many readers might have reached for examples of “plague literature” by Boccaccio, Daniel Defoe, and Albert Camus for wisdom and sustenance during the pandemic, but fresh generations of them consistently turn to Orwell’s two great dystopian novels, Animal Farm and 1984, when their lives are affected by leaders who get too big for their boots and erode civil liberties and human rights. Sales of 1984 skyrocketed in Russia following Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. Journalists invoke Orwell’s touchstone texts in articles on propaganda, hyper-surveillance, curtailed freedom of speech, and cancel culture. The message is clear: Orwell is still in demand because Orwell is still relevant.

Those who are Orwelled out perhaps won’t welcome the first major book about him of the new year. However, Paul Theroux’s Burma Sahib is a different kind of Orwell book. For one, it is about the man he really was, Eric Blair, and the five years he spent as a policeman in Burma before he adopted his nom de plume and became a published writer. Secondly, it is a novel, a fictionalized account of those years, and as a result, it doesn’t cling rigidly and restrictively to real events. Instead, with room to maneuver, Theroux blends hard fact with creative license to tell an engrossing story and produce a captivating portrait of the artist as a young man.

The novel opens in 1922 with 19-year-old Blair onboard a ship, sailing to the far corner of the British Empire and “to a fate he could not guess at.” His school days at Eton are behind him. Ahead of him is rigorous on-the-job training in the Indian Imperial Police in Burma, during which time he will maintain law and order and supervise the work of the local policemen. The voyage is long and made uncomfortable by the other British passengers, “an extended family of smug overlords and philistines,” some of whom, Blair is certain, will be his superiors at his journey’s end. He keeps his distance from them by holing up in his cabin with a book, but an invitation to dine at the captain’s table forces him to be sociable. Over dinner, a Scottish police officer gives him some advice: “Don’t you be new and naïve, my lad.” He urges Blair to stand firm and hold sway, to dominate and subjugate, then leaves him with a sentiment he will hear again and again: “Natives are scum.”

When Blair arrives in Burma, he and his fellow recruits are taken to meet two grandees who impart more wisdom. At Government House, the governor tells an increasingly incredulous Blair that his mission in the country is to teach British ideals to the benighted Burmans and show them how superior Western civilization is. At the Secretariat, the inspector general of police informs the group that they are approaching the “crime season” of January to June, their most demanding time of the year. When one trainee asks why these months see a higher incidence of criminal activity, he gets a pithy response: “Ask the first dacoit you arrest, note the answer, then beat him senseless about his head and shoulders.”

Blair is whisked off on the road to Mandalay to begin his police training in the city’s fort. There, he studies and carries out duties, but in his free time, he goes off alone to explore his surroundings, learn languages, write letters home, and lose himself in books. He also befriends Capt. Robinson, who has been cashiered from the army and branded a “degenerate” for his relations with native women. Robinson takes Blair under his wing and shows him the sights of Mandalay — in particular, Mother Majumdar’s pavilion on the river, the workplace of a Bengali madam and her team of Burmese girls.

Eventually, Blair is sent south on his first assignment. Instead of another city, he washes up in a small, squalid town in the Delta. In this landscape of murky marshes, flooded paddy fields, and stagnant canals, he leads investigations to track down and bring to justice thieves, rapists, arsonists, smugglers, and murderers. A second assignment takes him to another muddy backwater, this time to rein in an outspoken monk whose seditious sermons condemn British misrule.

There are additional postings, including to Rangoon and its environs, and for a while, Blair’s pressures at work are offset by the pleasure he finds in the company of friends and relatives. He is at his happiest when conducting an illicit affair with a self-assured married Englishwoman. Mrs. Jellicoe proves to be a kindred spirit, someone who “uttered Blair’s secret thoughts aloud, gave voice and meaning to his doubts, and articulated the contradictions in his heart that he had not revealed to anyone, even himself.” But after several blunders, Blair falls foul of his superiors and is banished to the back of beyond, out of sight and away from his love. Fortunately, he uses his exile to his advantage by chronicling his experiences, and in doing so, he feels a sense of renewal and comes to view writing not as recreation but rather as a vocation.

Burma Sahib sees Theroux drawing on his twin talents. Theroux, the accomplished travel writer, skillfully maps the lay of the land and transports his reader to one vividly depicted Burmese location after another. Cities are home to temples, palaces, pagodas, and colonial clubs, along with teeming, pulsing street life. The forests, with their cool shadows, scented air, and exotic flora and fauna, make for welcome retreats, far from the madding crowd. And “the spongy remoteness” of the Delta is more than a treacherous swampland. It is also a heart of darkness like the one Theroux evoked in The Mosquito Coast (1981).

At the same time, Theroux, the adept novelist, ensures his reader is invested in his protagonist’s journey — both his professional arc and his emotional trajectory. “There is a short period in everyone’s life when his character is fixed forever,” runs the book’s epigraph, a line from Orwell’s first novel, Burmese Days (1934). For Theroux, it was Orwell’s Burmese years that consolidated his character. We follow Blair as he is transferred from post to post, “starting again in a new bungalow, a new town, new servants, new neighbors, a new boss, new villains, the snakes and ladders of service in the Indian Imperial Police.” Constant throughout is a steady supply of racist officers who dismiss the Burmese as “dirt,” “rabble,” and “monkeys” and expect Blair to adopt a similar outlook. He is unable to, and as his guilt and self-loathing grows, so too does his contempt for his compatriots and his disillusionment with the “racket” that is empire.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Theroux’s Blair is fascinating, a mass of idiosyncrasies and incongruities. He despairs at being only “a half-made policeman” while acknowledging he is out of his depth and not cut out for this line of work. He is uncomfortable with the hierarchy imposed by the Raj yet indulges in sexual liaisons with his Burmese housemaids who address him as “master.”

Theroux fleshes his hero out further by incorporating character-building incidents from Orwell’s two essays, “Shooting an Elephant” and “A Hanging.” Some of the book’s details foreshadow aspects of Orwell’s life, from his obsession with rats to a “fruity” cough that causes his chest to rattle and his lungs to bubble. Particularly effective is Blair’s gradual transition to Orwell. “You will be a writer,” Mrs. Jellicoe tells him. “You will make your mark.” He did, and Theroux’s compelling origin story helps show how he found the voice and developed the attitude to do so.

Malcolm Forbes has written for the Economist, the Wall Street Journal, and the Washington Post. He lives in Edinburgh.