The fulcrum of Anton Chekhov’s life

Malcolm Forbes

In the summer of 1884, shortly after qualifying as a doctor in Moscow, Anton Chekhov began working at a district hospital. “I am in fine fettle, for I have my medical diploma in my pocket,” he reported to his editor. The countryside around him was expansive and scenic; he could go fishing, pick mushrooms, and enjoy the beauty of the local monastery. “Standing in the dim light of the aisle beneath the vaulted roof during an evening service, I am thinking of subjects for my stories,” he wrote. “I have plenty of subjects, but I am absolutely incapable of writing anything. I’m too lazy.”

A year and a half later, Chekhov was anything but. By then, he was balancing two professions and famously declaring that “medicine is my legal spouse, while literature is my mistress. When I get tired of one, I go and sleep with the other.” In actual fact, his mistress made more demands on his time. It took an effort to get into the swing of writing, and often, his medical work intruded. “Writing with interruptions is like an irregular pulse,” he grumbled. But when he had peace and was able to focus his creative energy, the words flowed. As they did so, his stories multiplied.

In 1886, 26-year-old Chekhov published 112 stories — some brief sketches, others comic skits, but most of them substantial tales. The following year, he published 64 stories, along with his first play, Ivanov. Over these two hectic years, he was at his most prolific, writing more stories than he would in the rest of his life. His achievements during this period raised his profile until he was viewed, and celebrated, as an emerging literary star. That star continued to ascend: When he died in 1904, he had secured the reputation of the most renowned writer in Russia after Tolstoy.

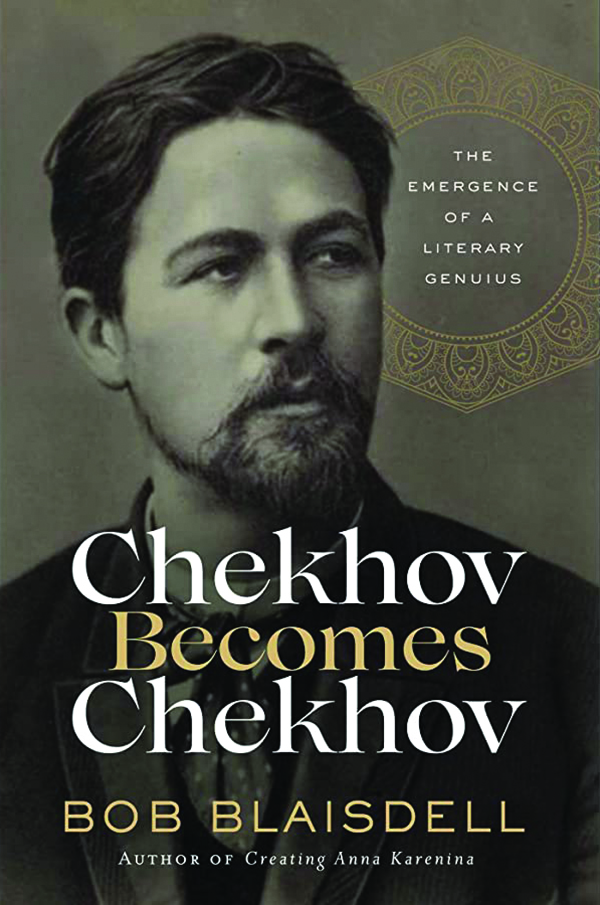

In his new book, Chekhov Becomes Chekhov, Bob Blaisdell centers squarely on those two breakthrough years that changed the author’s fortunes. Blaisdell, a professor of English at the City University of New York’s Kingsborough Community College, sets out to show how closely related Chekhov’s experiences are to his stories. Along the way, he analyzes Chekhov’s prodigious output, highlighting his tricks of the trade and flashes of genius.

Blaisdell describes how Chekhov shared a home with his parents and siblings and, as breadwinner of the family, supported them through his earnings. Despite his regular income, he was regularly beset by money worries. As a result, he increased his workload: As well as his medical duties and weekly deadlines for two publications, he started writing for a third. New Times, an important St. Petersburg newspaper, paid him well (he earned there more for one story than he did from the dozen pieces he produced each month for his frequent venue, Fragments), but to get everything done meant working flat out every day. Compounding Chekhov’s financial woes were health problems. He knew he had contracted tuberculosis two years previously but still refused to admit it to anyone. What he didn’t know in early 1886 was that he only had 18 more years to live.

However, Chekhov packed a great deal into the time he had left, not least in these two momentous years. Blaisdell’s trawl through Chekhov’s stories starts with those he wrote under the pseudonym Antosha Chekhonte. His first real story of 1886, “Art,” revolves around a bad-tempered, fault-finding, bone-idle villager called Seryozhka who, when he applies himself, is capable of artistic greatness. Blaisdell argues that Chekhov would have used this depiction of his feckless, listless protagonist to tease and motivate his work-shy yet talented older brothers.

In “Difficult People,” a story from later in the year, Chekhov traces family tension through a son’s confrontation with his tyrannical father — the latter not dissimilar to Chekhov’s own bullying and domineering father whose cruelty sullied his childhood. For Blaisdell, Chekhov’s explosive story “contains more power than any of his famous plays that involve family dramas. In this story, he caught lightning — and thunder — in a bottle.”

Other stories throw light on different aspects of Chekhov’s life or traits of his personality. The characters in “Frost” are given to nostalgic musings, much like their creator: “How much pleasure Chekhov, this young man full of redolent memories had in recollection,” Blaisdell gushes. After a brief synopsis of “An Avenger,” in which a man vows to kill his wife’s lover then wallows in misery, Blaisdell reveals that “Chekhov in the midst of his own despair and depression, mocked self-pity.”

Elsewhere we come across characters that lie to conceal their illnesses, or share Chekhov’s love of Easter, or need money to make ends meet. Some characters follow in Chekhov’s footsteps: A return trip down south to his home city of Taganrog inspires several stories set on the southern steppe, one of them painting a less than flattering picture of a town full of “scoundrels, blackguards, and rascals.” A visit to St. Petersburg in the grip of a typhus epidemic prompts a death-tinged tale featuring a disease-ridden antihero.

Blaisdell explains that during Chekhov’s frustrating and nerve-racking engagement, he was writing stories in which young couples are embroiled in toxic and destructive relationships. In a similar vein, when Chekhov was overburdened by his patients’ needs, his doctor characters crack up and break down.

But not all of these life-work parallels convince. At times, Blaisdell supplies tenuous links. In the story “Misery,” a sled driver tells his passengers about his son’s death, but no one listens sympathetically. In contrast, Blaisdell informs us that Chekhov was “an excellent listener.” The title character of “The Beggar” is reformed by taking on odd jobs that a lawyer offers him. According to Blaisdell, Chekhov was also “a do-gooder.” The young governess in “An Upheaval” is wrongly accused of theft and humiliated by the suspicion. Chekhov, writes Blaisdell, “could not bear being looked down upon.”

On other occasions, Blaisdell resorts to baseless speculation, such as when a character uses the phrase “rank and wealth” five times in a story. “Perhaps someone of ‘rank and wealth’ spoke this very phrase and it stuck in Chekhov’s craw,” Blaisdell surmises. A greater leap of faith on the reader’s part comes with Blaisdell’s claim that by reading a description of a character’s storytelling technique (“Scenes, characters, and situations were taken at random, impromptu, and the plot and the moral came of itself as it were”), “we might learn more about how Chekhov wrote his stories.”

Fortunately, Blaisdell’s missed connections and fanciful guesswork are in short supply. His dissections of and commentaries on each story are, by and large, colorful and insightful. Sometimes, he is refreshingly critical, dismissing one “problematic” tale as “squirm-worthy” and expressing his dislike for the ending of the miniature masterpiece “The Kiss.” Chekhov’s “model stories” are “graceful, quiet, inhabited by interesting, sympathetic, accidentally reckless people.” Those people come from all walks of life and are composed of all manner of flaws and contradictions: “Good people are prickly,” Blaisdell writes, “bad people are charming, weak people are resilient, strong people are brittle.”

Besides forensic close readings of the stories, Blaisdell fleshes out Chekhov by drawing on past biographies and personal correspondence. Chekhov’s letters see him berating his wayward brothers, bewailing his “dreary” writer’s life, scoffing at his newfound fame, and complaining that “money is as scarce as cats’ tears.” Some letters to aspiring writers are particularly illuminating, for they contain nuggets of wisdom about his craft. “In short stories it is better to say not enough than to say too much,” he advises. Writers should write about a range of themes, write in one sitting, and write “until your fingers are broken.”

The Chekhov that emerges from Blaisdell’s study is intriguingly multifaceted. He is sociable, reluctant to talk about himself, and prone to joking to hide pain and mask despondency. He is also generous, treating sickly peasants for free. Above all, he is a workaholic. It is easy to imagine him repeating the mantra Trigorin intones in The Seagull: “I must write, I must write, I must write.”

Readers in search of a comprehensive cradle-to-grave biography of Chekhov should look elsewhere. Those interested in the turning point in his life will find much to appreciate in Blaisdell’s study, which amounts to a smaller scale but no less captivating portrait of a master stylist and an astute companion piece to his remarkable work.

Malcolm Forbes has written for the Economist, the Wall Street Journal, and the Washington Post. He lives in Edinburgh.