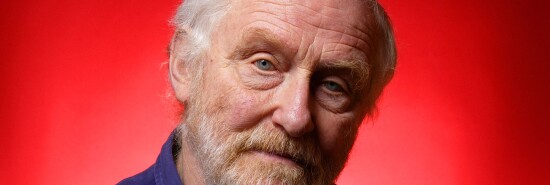

Mike Hodges, 1932-2022

Daniel Ross Goodman

The versatile British director of some of the most acclaimed gangster and science fiction films of the past 50 years died last week at his home in Dorset, England. Mike Hodges had one of the more varied and up-and-down careers of major feature film directors in recent memory. After having grown up in middle-class communities in English towns such as Salisbury and Bath, Hodges served in the Royal Navy for two years. The experience, which took him to virtually every port in Britain, gave him an exposure to working-class communities and concerns that could be discerned in his later gritty crime dramas.

Hodges’s parents wanted him to become an accountant, but, after having trained briefly for the profession, he chose a career in film and television. He got his first job in media as a teleprompter operator for the BBC, and thereafter began developing his own scripts for television series. Following a successful stint in the TV world, Hodges received his first chance in the world of film, an opportunity to direct the adaptation of a Ted Lewis novel. Hodges made good on it — and then some.

The 1971 film Get Carter, starring Michael Caine as a gangster out to avenge the death of his brother, was a major commercial and critical success. It was later hailed as the British Godfather and earned the plaudits of film critics such as Vincent Canby and Roger Ebert, the former of whom praised it for its “reworking the stylized conventions of an ancient genre — the car chases, the mysterious appearances of various Mr. Bigs, violence suddenly punctuated by moments of absurd sentiment, the contemporary variations on the wise-guy dialogue of 30 years ago.” The movie, which was remade in 2000 with Sylvester Stallone in the feature role, is now regarded as one of the classics of British cinema as well as one of the films that made Michael Caine into a movie star.

When Hodges reunited with Caine two years later for Pulp, the film proved to be less of a success, setting Hodges off in a wandering direction over the next several years. Other projects did not quite click with audiences or critics, such as The Terminal Man (1974), a kind of poor-man’s version of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange — another movie about the effects of technology and totalitarian controls on criminals that lacked the verve, wit, style, and sweep of Kubrick’s masterpiece.

Hodges rebounded somewhat in 1980 with Flash Gordon, a sci-fi romp starring Timothy Dalton, Max von Sydow, and Sam J. Jones, with a memorably and eye-poppingly colorful production design and a fittingly exuberant score by Queen. Although the film’s archness and satiric bent flew over the heads of some critics, more perceptive viewers appreciated the movie’s playfulness and its unapologetically campy take on the serious space opera genre that Star Wars and Star Trek had popularized. As Roger Ebert wrote about the movie that is now considered a cult classic, “Flash Gordon is played for laughs, and wisely so. … It’s fun to see [the space opera] done with energy and love and without the pseudo-meaningful apparatus of the Force and Trekkie Power.”

In the ’80s and ’90s, Hodges bounced around between movies and television without ever quite being able to duplicate the success he had realized with Get Carter or Flash Gordon. He also produced and directed plays for radio and theater, working with some of the finest British stage actors of the era, such as Michael Sheen and Michael Gambon, without ever giving up his hopes for another hit movie. This long-awaited-for next hit finally happened for Hodges in 1998 with the film Croupier, though in a somewhat unexpected manner.

In Croupier, Hodges returned to the genre that had launched his directorial career: the crime film. Working with a largely unheralded cast that included a still mostly unknown Clive Owen, the movie centers on an aspiring writer (Owen) who takes a job at a casino to supplement his income and quickly becomes embroiled in a dicey robbery scheme. The movie flopped when it opened in the U.K., causing Hodges to think that his film career was over. But when it later opened in the U.S., it turned out to be a surprise hit, giving Hodges a second life in movies and also giving Owen his start in movies as a leading man.

While film purists will likely continue to point to Get Carter as the centerpiece of Hodges’s oeuvre, in my view, his most important contribution to the world of film will prove to be Flash Gordon. In a movie marketplace that continues to be dominated by superhero productions designed to become tent-pole films for a whole host of other entertainment products, from not only sequels and prequels to TV shows to even toys, video games, and amusement parks, Flash Gordon shows that a film based on a comic book can be a fun, inventive standalone movie without needing to be the committee-workshopped springboard for an entire dreary franchise. If current and future directors learn from Hodges’s life and the example he set with Flash Gordon, our film culture could once again return to a healthier and more imaginative place.

Daniel Ross Goodman is a Washington Examiner contributing writer and the author, most recently, of Somewhere Over the Rainbow: Wonder and Religion in American Cinema.