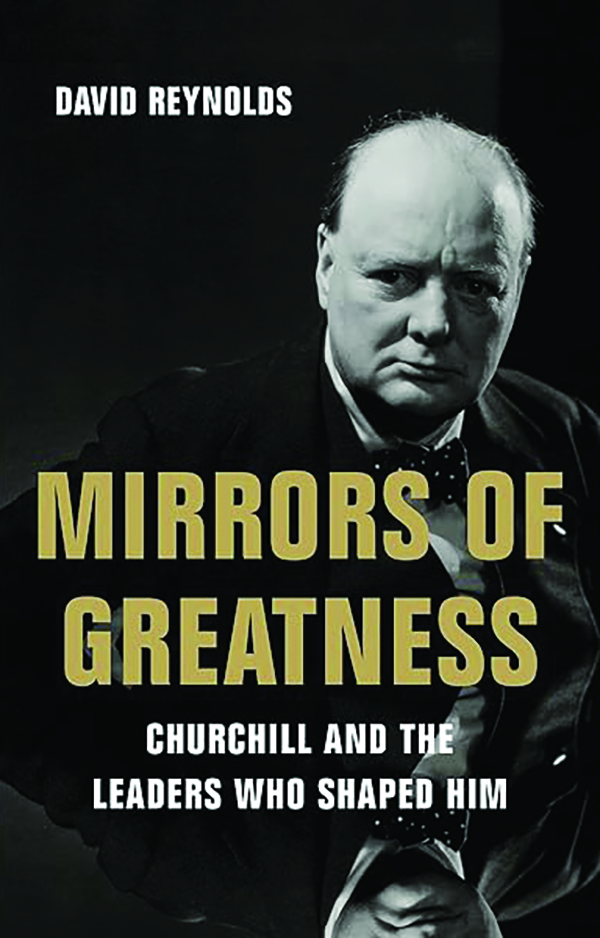

“Winston Churchill appeared to me,” Charles De Gaulle wrote in 1959, “from one end of the drama to the other, as the great champion of a great enterprise and the great artist of a great history.” Churchill was not only the author, both literally and figuratively, of a great history, but he has also been one of its more enduring subjects. Few men have been both more studied and more mythologized. And David Reynolds’s new book, Mirrors of Greatness: Churchill and the Leaders Who Shaped Him, helps explain why.

Meant as a successor volume of sorts to Churchill’s own 1937 work, Great Contemporaries, which examined the lives and careers of 25 of the parliamentarian’s peers, the book explores the great British war leader through character sketches of eleven of his contemporaries. Reynolds is no stranger to Churchill. The famed Cambridge historian and frequent BBC presenter has authored numerous works and narrated several documentaries on the legendary British prime minister. But by exploring Churchill’s life through the careers of his contemporaries, friend and foe alike, Reynolds hopes to “discover a novel way both to narrate and also to interrogate this remarkable life.”

He succeeds in spades with a book that is both readable and informative. For millions across the world, Churchill remains the greatest Briton of all time. On the 150th anniversary of his 1874 birth, interest in his long and colorful life hasn’t abated. Indeed, judging by the hundreds of biographies on the man, it seems likely to endure long into the future. At last count, there were more than 1,150 biographies on him, the first written by Churchill himself.

In his long career, Churchill was often wrong. But on the chief issue of his time, the danger posed by Adolf Hitler, he was both prescient and formidable. His relations with other contemporaries, notably Gandhi, show that he was, in key respects, a man of the Victorian Age, with all its biases and shortcomings. Each chapter, Reynolds notes, “is a kind of two-way mirror.”

Churchill was born at the height of the Victorian Empire, fighting in battles that spanned many of its frontiers, including the Battle of Omdurman, the last cavalry charge. He died in 1965, well into the nuclear age, having played major roles in two world wars, the dawn of the Cold War, and both the peak and decline of empire and colonialism.

Churchill wasn’t just a participant in great historical events; he also recorded them in his books, many of them popular. In his time after office, he authored 58 books and hundreds of articles and essays. In 1953, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for literature. History’s view of Churchill, Reynolds notes, “has been shaped as he intended, by his estimate of himself.” Churchill didn’t just make history — he “wrote himself into history, to a degree unique in modern times.”

To put it mildly: Churchill could write. This alone makes him unique among his political contemporaries, British and otherwise. Several of his aides have left accounts noting his constant quest for the perfect word or turn of phrase. But this isn’t solely what De Gaulle meant when he referred to the man’s “artistry.” Rather, he was striking at the heart of what made Churchill great: his conception of himself as an actor on the world stage, playing an irreplaceable role. As he said of appointment as prime minister in the annus horribilis of 1940: “I felt as if I were walking with destiny, and that all my past life had been but a preparation for this hour and for this trial.”

Churchill’s obsession with the right word wasn’t just a sign of his literary prowess but of his fundamental understanding of the importance of imagery, of showmanship. Churchill’s legendary speeches before the House of Commons were well prepared, the periodic pauses timed for dramatic effect. Even his fiercest critics and rivals like Neville Chamberlain and Clement Attlee often found themselves spellbound by his performances.

The late American historian Shelby Foote once said of Abraham Lincoln: “Almost everything he did was calculated for effect. He knew exactly how to do it.” The same might be said for Churchill, contravening the opinions of many of his critics who often charged him, sometimes correctly, as being impulsive.

In his 2006 book, In Command of History, Reynolds highlighted how Churchill shaped opinion to his own ends. But as he makes clear in his latest work, this was made possible by Churchill’s own “obsession” with greatness. “Lacking any belief in an afterlife, and convinced he would die young, he was determined to leave his mark on history, like the leaders of old who had been dubbed ‘the Great’—from Alexander of Macedonia to Frederick of Prussia.”

Churchill wasn’t born great. Nor did he have greatness thrust upon him. Rather, he achieved greatness because he constantly pursued it, modeling himself after his heroes. First among them was his own father, Randolph Churchill, the subject of Reynolds’s first chapter.

But the truth of Randolph Churchill’s life was vastly different from the alternate reality held by his son. The elder Churchill was erratic, vain, and prone to making terrible career choices. At various points in his short life — he died at the age of 45 when Churchill was only 20 — Randolph threatened his Tory Party colleagues, one of whom, Lord Salisbury, eventually bested him in parliamentary battle. He even attempted to blackmail Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s eldest son and heir. Judgment was not his strong suit, and despite his oratorical gifts and swift ascent, his was a career crowned more in failure than glory.

Yet even as an old man, Churchill revered his father, overlooking his many flaws and working feverishly for an approval that could never come. Randolph bequeathed Churchill with the gift of a name known in politics but also an infamous legacy. Other father figures would await, notably David Lloyd George, Winston’s first mentor in Parliament.

Lloyd George had all of Lord Randolph’s cunning but none of his impulsiveness. As Reynolds notes, Churchill willingly deferred to the man known as the “Welsh Wizard,” admiring his skills while often privately disdaining his deviousness. For the sometimes-imperious Churchill, it was the rare relationship in which he was but the “servant” and Lloyd George was the “master.” But despite his frequent servility in their partnership, Churchill would also surpass his onetime mentor. Lloyd George helped lead Great Britain to victory in World War I, but it would be Winston who would rise to true greatness two decades later.

Ultimately, Mirrors of Greatness illuminates why there is such an enduring fascination with Churchill. He sought greatness and was often surrounded by it, often creating his own reality. As his doctor, Lord Moran, observed: “Where people are concerned, Winston Churchill exists in an imaginary world of his own making.”

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Sean Durns is a Washington, D.C.-based foreign affairs analyst.