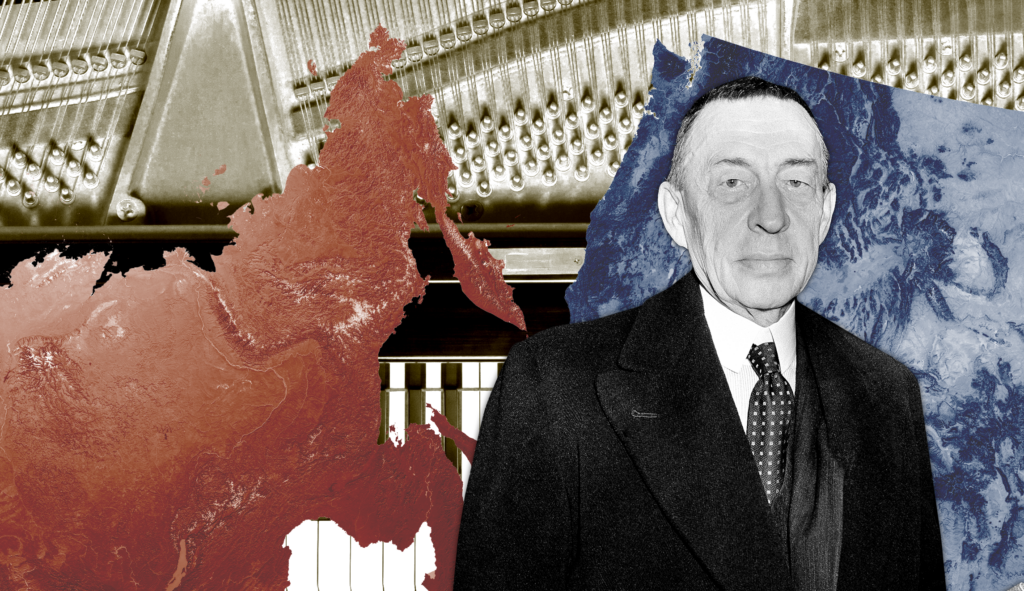

When the composer Sergei Rachmaninoff left Russia with his wife and two daughters at the end of 1917, he left behind all his works except the recently revised Piano Concerto No. 1 and the vocal score for an opera called Monna Vanna, which he would never complete. He also left behind the family’s beloved country estate, Ivanovka, in the Tambov region, an apartment in Moscow, and most of his personal belongings. He would never return.

384 pp., $29.95

Ivanovka, in particular, meant a lot to him, as Fiona Maddocks writes in her account of Rachmaninoff’s exile, Goodbye Russia. He spent two summers there as a youth with his future wife’s family (she was his cousin) and fell in love with it. When he took over the houses and attached fields and farms in 1909, he spent most of his earnings as a composer and conductor making repairs and updating them. In 1931, 14 years after abandoning it, he still thought of its “broad landscape”: “There are none of the beauties of nature that are usually thought of in this term — no mountains, precipice, or winding shore. This steppe was like an infinite sea … Sea air is often praised, but how much more do I love the air of the steppe, with its aroma of earth and all that grows and blossoms.”

The comparison of the fields around Ivanovka to the sea is not random. During his time in the States, Rachmaninoff would keep the same seasonal schedule he did in Russia — fall and winter in the city (New York instead of Moscow) followed by spring and summer in the country. Other than a summer in Goshen, New York, the Rachmaninoffs always chose a coastal escape in the States, first Palo Alto, California, then Locust Point, New Jersey. As beautiful as these places were, it seems, they still did not match the beauty of Ivanovka for Rachmaninoff. He would eventually become attached to a summer home he built on the shores of Lake Lucerne in the early 1930s, but this, too, would be abandoned at the outbreak of WWII. He would never see it again either.

When Rachmaninoff left Russia, he was at the peak of his career as a composer and conductor. His Prelude in C-sharp minor, which he performed in 1892 shortly after graduating from the Moscow Conservatory, marked him as a young composer of promise. After a disastrous Symphony No. 1, which premiered in St. Petersburg in 1897, he returned in 1901 with the massively successful Piano Concerto No. 2. It was performed in Germany and Austria shortly afterward, then in London in 1908 and Philadelphia in 1909. His Symphony No. 2 followed in 1908, Isle of the Dead in 1909, Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom in 1910, and The Bells in 1913. He was named the vice president of the Imperial Russian Musical Society in 1910, but he became increasingly concerned about the political situation in Russia. Shortly after Nicolas II abdicated, it became clear to him that he had to leave. “But where and how,” he wrote to the foreign minister in the provisional government, “is it possible?”

The opportunity came “unexpectedly,” Maddocks writes, with an invitation to give a series of concerts in Scandinavia. He applied for a visa and arrived in Stockholm on Christmas Eve. After concerts in Norway and Sweden, he received an invitation to perform 20 concerts in America. “The fees were high,” Maddocks writes, and Rachmaninoff, always concerned about money, made up his mind that his future was in America.

He and his family arrived on the eve of the Armistice of 1918. Newspapers were preoccupied with the end of the war, but Rachmaninoff’s arrival warranted a note in the New York Times nonetheless: “Composer Escapes from Russia to America to Rest and Work.” His American tour in 1909 had been successful, and his Prelude in C-sharp minor, which was an international hit thanks to the performances of his cousin, Alexander Siloti, created immense interest in the composer. Seven months before Rachmaninoff arrived in America, George L. Cobb had published the sheet music for his “Russian Rag: Interpolating the World-Famous Prelude by Rachmaninoff.” It was one of the most popular songs of the year. A foxtrot version soon followed and, later, a jazz version. Rachmaninoff wished he had never written the song and avoided playing it at first but soon relented. His decision to play his own arrangement of “The Star-Spangled Banner” at his first concerts proved unsurprisingly popular. He had a sense for what audiences wanted to hear and avoided experimental compositions, which he disliked, much to the chagrin of many critics.

His first 20 concerts in the States were a success and launched a 25-year international performing career, with Rachmaninoff performing over 70 concerts some years, mostly in the United States at first, then in the United Kingdom and across Europe.

His English was never fluent, and he surrounded himself with Russian emigres in the States and abroad. Even his doctor was Russian, as was the help in the house. Tall and thin, with dark eyes, and reserved in the extreme in public, he was often compared to a ghost or an undertaker by journalists. People who knew him well, however, remembered him as an affectionate and playful man who loved to laugh. He worked hard during concert season, packing his schedule to the brim to avoid wasting time on the road, and he kept to a strict if less arduous schedule in the summer: breakfast, morning practice, lunch, afternoon outings, or games. On the weekends, friends would visit and sometimes sing and dance until morning.

Generous to a fault, he gave thousands of dollars to friends and family and performed at fundraisers whenever needed. A faithful Orthodox until the end of his life, he was one of the first to contribute to the founding of Christ the Savior Russia Orthodox Church in 1924.

Rachmaninoff was one of the first composers to record his own work. When a fellow Russian, Igor Sikorsky, wanted to build a twin-engine, 14-passenger plane in 1923, Rachmaninoff wrote him a check for $5,000. He was invited to serve as the company’s first vice president, which he accepted. He loved cars and took particular care of his Lincoln limousine. When he began touring regularly in Europe and spending summers in Switzerland, he would ship the Lincoln ahead every year, giving detailed instructions to his agent about its care.

He composed only six works after leaving Russia in 1917 until his death in 1943, none of them masterpieces. It could be that his music was inextricably connected to his homeland. “I am a Russian composer,” he remarked in 1941, “and the land of my birth has influenced my temperament and outlook. My music is the product of my temperament, and so it is Russian music.”

At times, Maddocks does little more than string together letters from Rachmaninoff’s time in America and Europe. Still, it is a suitably readable account of this neglected period from one of the 20th century’s greatest composers.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Micah Mattix is a professor of English at Regent University.