How a Cuban spy operated inside US intelligence and how she was caught

Sean Durns

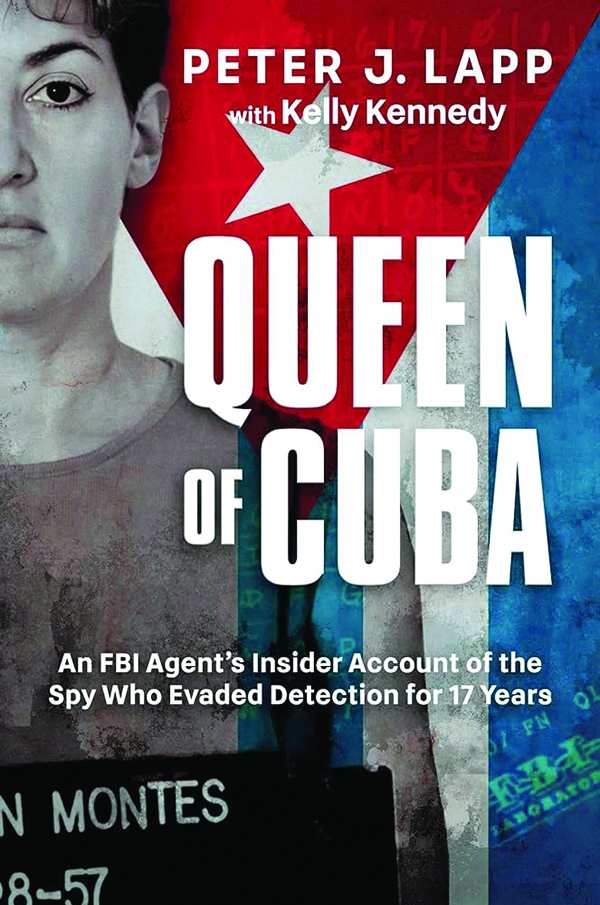

For nearly two decades, one of the world’s most successful spies hid in plain sight. Ana Montes, a “superstar” employee for the Defense Intelligence Agency, was a highly decorated and well-respected analyst on Latin American affairs. But as Peter J. Lapp and Kelly Kennedy recount in their new book, Queen of Cuba, Montes’s loyalty was to Fidel Castro’s Cuba, not the United States.

These authors tell the story like no one else could. Lapp is a retired FBI agent who was intimately involved in the case. He brings an insider’s perspective and a sense of humor. Co-writer Kennedy is a veteran reporter of national security affairs and a talented wordsmith. Together, the two have authored a book that is highly readable and informative. It is also deeply disturbing.

DAVID MAMET’S LIFE IN HOLLYWOOD

To the broader public, the Montes story was eclipsed by the 9/11 terrorist attacks that took place the same week as her arrest. But for historians of intelligence studies and spycraft, the Montes case stands apart for its peculiarities and impact. Montes was one of the single most damaging spies in modern history, ferreting information to Communist Cuba and its allies for 17 years.

The Cuban intelligence services have long punched above their weight. As former CIA analyst Brian Latell noted in his 2012 book Castro’s Secrets, “Many retired CIA officials stand in awe of how Cuba, a small island nation, could have built up such exceptional clandestine capabilities and run so many successful operations against American targets.” In Latell’s opinion, “Cuban intelligence … ran circles around both” the CIA and FBI.

When Castro seized power in 1959, Cuba lacked a foreign spy agency. Under Soviet auspices, Havana created one in 1961. Initially called the Direccion General de Inteligencia and later renamed, the most important intelligence service in Cuba began training its officers in Moscow in 1962.

During the Cold War, Cuba utilized its spy agency to devastating effect. The DGI helped extend Castro’s reach far beyond Cuba’s shores. The DGI helped train and arm Palestinian terrorist groups, operating as far away as Algiers and Damascus and playing a key role in Cuban intervention in Angola and elsewhere in Africa in the 1970s.

But Cuba’s spies would pull off some of their most daring operations in the U.S. In 1987, Florentino Aspillaga Lombard, a top apparatchik in Castro’s intelligence services, defected to the U.S. He soon exposed dozens of Cuban double agents who had infiltrated American society. Many had been living in the U.S. for years. Montes, however, escaped the notice of American counterintelligence officials. She would continue to do so for a long time.

Unusually, Montes had been recruited prior to her being hired by the Defense Intelligence Agency. Equally unusual, she wasn’t interested in being paid for her services. She was a “true believer,” as Scott Carmichael, a Defense Intelligence Agency official who investigated her, put it.

Montes grew up in a middle-class family with Puerto Rican roots. Her father was a stern, and sometimes abusive, parent who served as a psychiatrist in the U.S. Army. Montes’s relationship with her father played an important role in her need to identify with the underdog, as well as her desire to be simultaneously secretive and defiant.

Montes had been recruited to spy for Cuba by a friend named Marta, who worked both for the U.S. Agency for International Development and Castro’s Cuba. Marta hung around Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies, hoping to find possible spies for the regime. Montes, a graduate student at SAIS, hardly needed convincing. As Lapp and Kennedy note, “By the time she met her first spy, Ana had already fallen for the cause.”

During the 1970s and early 1980s, the Soviet Union was on the march, expanding its involvement in Latin America and elsewhere in the Third World. The U.S. response provoked ire among the Western Left, including Montes. Montes, the authors note, “didn’t think the United States should involve itself in other countries’ affairs.” She “hated the colonialist feel of U.S. involvement.” Of course, Castro’s Cuba was itself actively exporting communism throughout the world. And its patron, the Soviet Union, was deeply imperialistic. Both were authoritarian governments that brutally repressed their own people. Yet when others, including Lapp, pointed this out to Montes, she demurred.

An anti-American ideologue, Montes nonetheless chose to work for the government she hated. She was initially assigned to Central American hot spots but eventually found herself tasked with an overview that included analyzing the very country she was spying for.

Montes was an unusual spy. As the authors observe, her career “outlasted the majority of spies.” Montes avoided detection by hiding in plain view. “She wanted nothing to do with dead drops” and often met her handlers in broad daylight, over dim sum at Chinese restaurants in the Washington area. Indeed, she wasn’t even trained in countersurveillance techniques by Cuban agents.

But Montes’s success at avoiding detection wasn’t purely the result of her unconventional methods. As Lapp and Kennedy note, the spy catchers weren’t looking for a woman. Further, the notoriously hardworking Montes was considered a “superstar” by her superiors. It seemed unlikely she would be a turncoat. And she was working hard — for Cuba.

Montes used her status to quash opposing viewpoints, including efforts to support Cuba’s designation as a state sponsor of terrorism. Indeed, the amount of damage she caused is difficult to calculate. Montes almost certainly leaked information that led to the death of a U.S. Army Special Forces soldier.

Montes even gave up information about a highly classified special access program that she was, to use a spy term, “read into.” Her decision to expose that program could have earned her the death penalty. After Montes was caught, Lapp asked her if she was aware of the consequences. “Absolutely,” she told him. “I knew how bad it was. It was one of the only times I paused before sending information.” Yet she still went ahead and sent the information to her handlers, believing that “if it’s that important, then the Cubans should know.”

In fact, Montes was so determined to feed the Cubans information that she even did so when she believed she was under surveillance. At nearly every turn, she steadfastly stuck to those she called “her friends,” the Castro regime.

Her ultimate downfall was the result of both accidents of fate and determined investigators. Disillusioned Cuban intelligence operatives who, at great personal risk, fled to the U.S., also played a key role in helping authorities put the pieces of the puzzle together. It became a race against the clock to get enough evidence to lock Montes up before she was made aware of American war plans for Afghanistan — plans that Lapp and others feared Cuba would share with Russia and other American enemies.

Even after her imprisonment, Montes remained defiant and unrepentant. She expressed few regrets and treated her interrogators with the same confident arrogance that had made her so unpopular with her Defense Intelligence Agency colleagues. The portrait that emerges from Lapp and Kennedy’s book is dark. Lapp seems to be haunted by the Montes case and what it says about the human capacity to deceive and rationalize.

Ideologues, the liberal French philosopher Raymond Aron once wrote, can tolerate “the worst crimes as long as they are committed in the name of the proper doctrines.” As the Queen of Cuba makes clear, Montes was a fierce ideologue, and one who did incalculable damage to the U.S.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Sean Durns is a Washington, D.C.-based foreign affairs analyst.