Dick Cavett: The last of the great conversationalists

Peter Tonguette

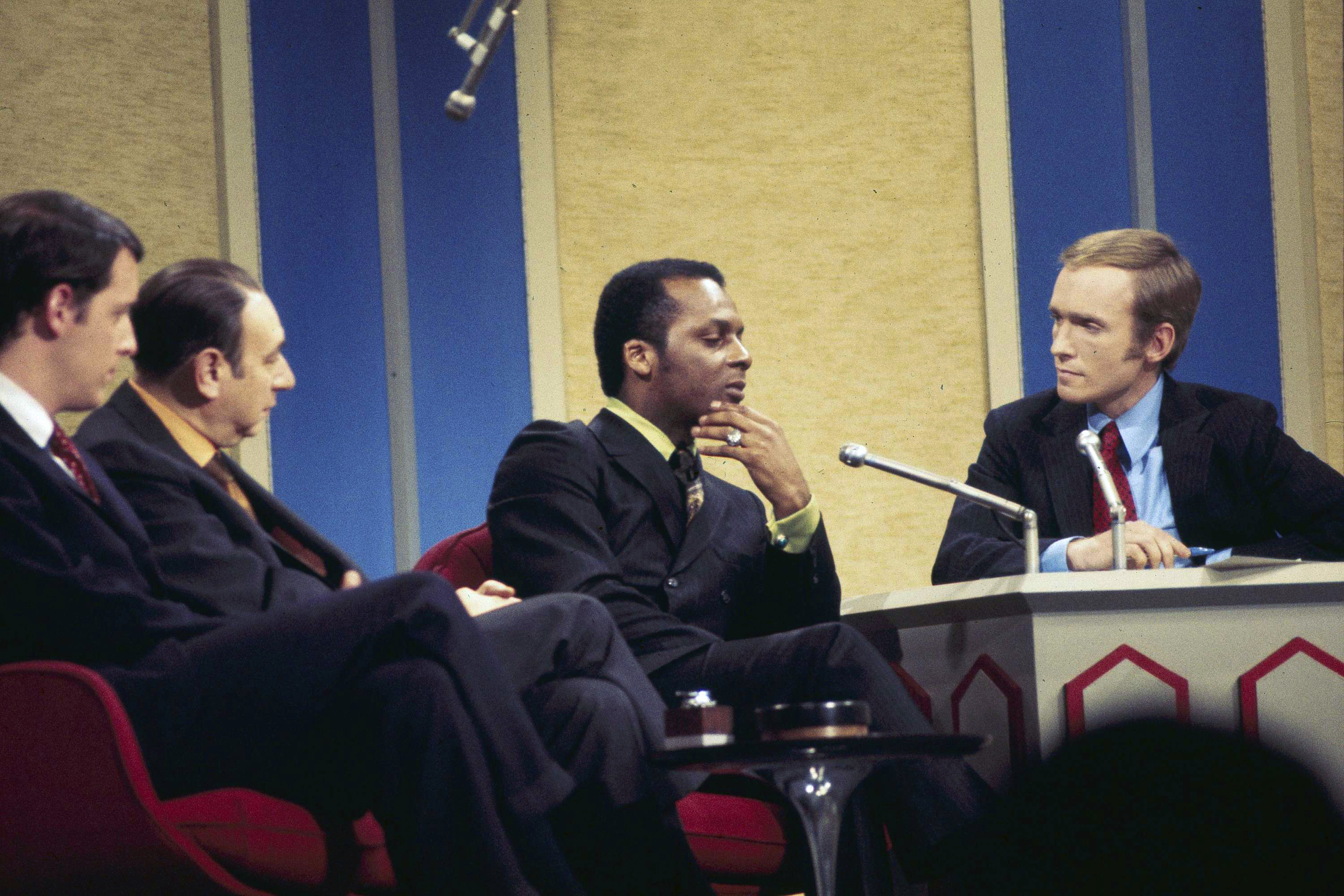

Video Embed

We don’t know how to talk to each other these days, and that includes those who are paid to do the talking. The current generation of late-night talk show hosts, supposedly professional conversationalists, fail miserably at the job. Jimmy Fallon on The Tonight Show is awkward, giggly, and forced in his enthusiasms, while Stephen Colbert on The Late Show is stern, plodding, and ponderous. Credit Jimmy Kimmel for at least having a sense of joie de vivre, but his joie is strictly from the Jackass school of extroversion: The man is no great communicator but merely a back-slapping post-post-adolescent.

Even the conversationalists who once made political talk shows bearable have, one by one, disappeared: On Meet the Press, the professional, balanced Garrick Utley and the amiable, genuinely curious Tim Russert have been supplanted with a series of strident self-appointed defenders of democracy: David Gregory, Chuck Todd, and now the lamentable Kristen Welker. Even Tucker Carlson is far from a natural interlocutor. To his credit, he does seem to listen to people, though, with his eyes in a confused stare and his mouth ever-so-slightly agape, his laugh is no less ill-timed and feigned-sounding than Jimmy Fallon’s.

DAVID MAMET’S LIFE IN HOLLYWOOD

These people like to talk, but they tend to talk at you. At best, they are monologists. None of them suggests someone you would wish to sit beside on a long bus or plane ride, an essential precondition for appearing on TV for upwards of an hour at a time. We could imagine shooting the breeze with David Letterman, or trading pro-football scores with Tim Russert, but would Stephen Colbert even look your way if you didn’t have a movie or show to promote or if you seemed to be a member of the MAGA movement? He’s a cold fish.

I thought of this unfortunate state of affairs recently while watching some old episodes of The Dick Cavett Show, which, in a testament to the conversational powers of its host, stayed on the air, across various stations and channels and with a few periods of interruption, between 1968 and 2006. Cavett, who turned 87 in November, is the last of the great conversationalists, the only survivor of the truly classic era in American talk shows: He learned his craft from pioneers such as Johnny Carson and Jack Paar. And during the peak years of his success, he competed for viewers with worthy adversaries, including Merv Griffin, David Frost, and Tom Snyder. For all their differences in style and technique, all of these men had something in common: They had the gift of engaging with a whole wide world of people — drawing them in, nudging them to open up, challenging them when necessary. If William F. Buckley on Firing Line made use of strategic warfare on his show, Cavett maintained a tone closer to the doctrine of Swiss neutrality.

Cavett’s own disposition informed the tone of the show. The sage of Gibbon, Nebraska, Cavett was blessed with a dry, uninflected voice seemingly from birth, as well as a mild, unflappable manner that suggested to guests he would be a fair interviewer and impartial arbiter. His demeanor is a bit like a quieted-down Woody Allen, whose acquaintance he made while working behind the scenes on The Tonight Show and whose friendship he has maintained for all the decades since. (Cavett has a cameo in Annie Hall, and he also turned up in Robert Altman’s H.E.A.L.T.H., Tim Burton’s Beetlejuice, and more.) The two even share a reputation for psychological afflictions — Allen has wrung comic gold from his hypochondria, while, rather more ominously, Cavett has openly struggled with depression — and a penchant for Brooks Brothers-style wardrobes.

Perhaps this is why such an impressive throng of personalities agreed to appear on The Dick Cavett Show, everyone from John Lennon to Katharine Hepburn, Marlon Brando to Orson Welles. There, they were greeted not by a Grand Inquisitor but a Meek Needler. That is not to say our genial host was without opinions, but he expressed them much as Allen did in his prime: with a one-liner, simply delivered, rather than a spear. Cavett was the ideal straight man for what his show’s bookers must have known would be wild, out-of-control guests, including Salvador Dali, whose incoherent ramblings were met by the host’s sober attempt to summarize them. “The cauliflower was the same pattern as the sunflower?” Cavett asked Dali at one point; “The same rhinoceros that you mentioned earlier?” he asked at another.

Cavett’s relatively straight-laced persona made him ideal for interacting with what now looks like the insanely foolish and self-righteous counterculture generation. He was never mean, but he managed, by his very presence, to make a few points. Cavett politely queried Jimi Hendrix about his tendency to destroy things onstage and gamely tried to ask question after question of the astonishingly nonresponsive nonactors of Michelangelo Antonioni’s incomprehensible Zabriskie Point, Mark Frechette and Daria Halprin. “There’s more to the story, right?” Cavett calmly asks after one of Frechette’s evasively attenuated answers.

Most famously, Cavett once found himself convening a meeting of notorious then-enemies Norman Mailer and Gore Vidal, who were in the midst of a yearslong literary feud that, thanks to their appearance on his show, briefly fell into public view. He gently goaded Gloria Swanson to reveal what she found so offensive about a performance by Lenny Bruce (“Could you describe the outlines of what you thought you saw?”), but he did so in such a way as not to offend his guest. He asked the Archbishop of Canterbury about church matters, George Cukor about Greta Garbo, and Fred Astaire about his best dance partners. In truth, Cavett always had a greater affinity for old-timey figures than the weirdos of the hour. He nurtured a most fruitful friendship with a senescent but still sharp-witted Groucho Marx, a relationship documented in the terrific 2022 PBS documentary Groucho & Cavett.

Cavett lives on through such retrospective appearances and, of course, in the digital afterlife of YouTube, where Mailer and Vidal are forever brawling, Dali is forever confounding, and Groucho is forever leaving his pal in stitches. Through these clips, which, in 2024, have the quality of dispatches from another planet, perhaps all of us will relearn the art of conversation that Cavett had once mastered: It is better to listen than to ignore, better to make a joke than give a lecture, and better to ask questions, even pointed ones, rather than assume you know all the answers. Let Dick Cavett show us the way.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Peter Tonguette is a contributing writer to the Washington Examiner magazine.