David Mamet’s life in Hollywood

Peter Tonguette

Since the dawn of movies, major writers have been seduced, cajoled, and otherwise enticed to pull up stakes for Hollywood. There, the routine goes like this: Previously autonomous authors submit themselves to tyrannical studio bosses and egomaniacal directors, churn out screenplays that may or may not reach the screen in versions that may or may not reflect their intentions, and get paid large sums in the process.

Yet the studios’ practice of co-opting our leading literary lights has produced mixed results. William Faulkner is credited as co-writing a pair of masterpieces for Howard Hawks, To Have and Have Not and The Big Sleep. But Dorothy Parker, Gore Vidal, and Tom Stoppard are but a few of the major writers who, along with the occasional worthwhile movie assignment, contributed to (or at least were credited on) some seriously subpar movies. Such work tends to breed contempt, and a number of the aforementioned later spoke with scorn of their days in the California sun. “There’s less here than meets the eye,” Parker once said.

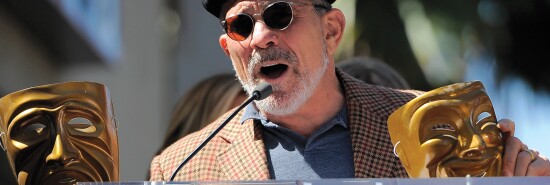

Now, it is David Mamet’s turn to bitingly excoriate, explicate, and sometimes exonerate the hand that fed him. Mamet’s track record is nothing to sniff at. In fact, on the strength of his reputation as a playwright, his name recognition, and his undeniable gift for plotting and tough-guy patois, Mamet carved out a respectable filmmaking career for the better part of four decades.

He wrote film versions of his plays (Glengarry Glen Ross, American Buffalo), directed his own original screenplays (including House of Games, Homicide, and Spartan), and wrote a fair number of large-scale, big-budget productions, not the least of which is Brian De Palma’s The Untouchables. I still remember seeing no fewer than three high-level Mamet-written films in 1997 alone, each of which was at least good: his own The Spanish Prisoner, the rather rote but still engaging thriller The Edge, and the finely wrought political satire about Bill Clinton Wag the Dog. To put it another way, Mamet may have less to bitch about than, say, Parker or F. Scott Fitzgerald. But his bitching is more interesting than most.

Even Mamet’s employers had to have known that he would eventually report back on what he had seen out West. In fact, in the midst of his early success with the studios, Mamet penned a play that served as an exposé of Hollywood, 1988’s acclaimed Speed-the-Plow. About 12 years later, he wrote and directed a film that, while relatively gentle and companionable by his standards, more or less did the same, 2000’s State and Main.

By that point, Mamet’s success rate in the movie business was about to start waning: between 2001 and 2008, he directed just three feature films and wrote but one blockbuster, 2001’s Hannibal. His most recent directorial work, the 2013 HBO true-life tele-pic Phil Spector, is now a decade old. Concurrent with this professional decline has been Mamet’s gradual public disclosure of his conservative politics, an unveiling that commenced with a 2008 Village Voice piece titled “Why I Am No Longer a ‘Brain-Dead Liberal,’” accelerated with his assiduously argued 2011 book The Secret Knowledge, and went past the point of no return with his defenses of the 45th president in interviews and talks.

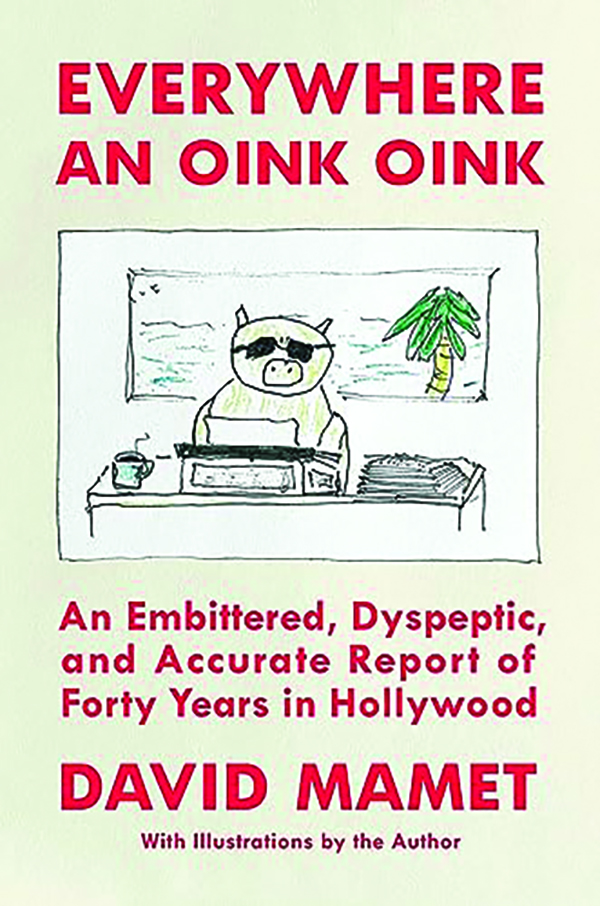

As the years have gone on, then, Mamet has had less and less to lose by making himself unemployable in Hollywood, which may be the final outcome of his new book, an invigorating savaging of the business of making movies. Everywhere an Oink Oink has the quality of a book written in one night or at least a single burst of welled-up wrath. Without much regard for structure or shapeliness, Mamet offers expressions of outrage, shock, horror, and, from time to time, honest appreciation. “I am willing to think ill of anyone,” he writes at the start, “so I suppose I have an open mind.”

Mamet entered the movie business on something of a dare and continued in it with his eyes wide open. As he tells it, a friend of his was auditioning for a role in Bob Rafelson’s The Postman Always Rings Twice. “I asked her to tell Bob that if he didn’t hire me to write the script he was nuts,” Mamet remembers. And because Rafelson was a promiscuous risk-taker, he hired the playwright to write his first screenplay. At their first meeting, Rafelson, who had been fired from his last picture on the heels of an altercation with an executive, told Mamet: “They’re going to tell you that I threw an executive through a plate glass window. It’s true.” Mamet reflects: “That set the tone for forty years in Hollywood.”

Most of Mamet’s experiences, though, are not so much brushes with violence than encounters with ignorance. The Writers Guild denied Mamet “first position credit” on Wag the Dog, a script he wrote solo and in ignorance of a previous version by another writer. “The Review Committee, three writers, ruled me the loser,” Mamet recounts. “Then I got a call from one of the three, who said the other two had not even read the scripts but simply looked at the dates of submission.” Such lapses in judgment were not uncommon in his experience. Hired to adapt Akira Kurosawa’s High and Low for director Mike Nichols, Mamet was summoned to meet Nichols and producer Scott Rudin, who insisted that the script must be about greed and the protagonist must be punished due to his alleged greed. “Fellas,” Mamet said, “it has nothing to do with greed.” The movie was never made.

On one of Mamet’s movies, here unnamed, an unscrupulous producer set aside no funds for post-production, the phase of filmmaking that involves editing, sound, and scoring, but promised the filmmaker that, if he shot the film carefully and economically, he would have a contingency fund at his disposal to finish up. Want to guess how this story ends? “Where, I asked my then colleague (one of the producers), was the contingency?” Mamet writes. Vanished. “It had joined the killer of Ron and Nicole,” Mamet reflects. Later, on Phil Spector, Mamet is assured by HBO that he would have final cut, but a meddlesome executive still turned up to suggest, out of context, various cuts. “This Executive didn’t know what he was looking at — how could he, as he hadn’t lived with the thing as a script, on the set, or through days in the cutting room,” Mamet asks, sensibly.

Throughout, Mamet distinguishes the actual artisans in movies, including, certainly, the writers and directors, but also the stuntmen, armorers, dressers, and character actors, from the businessmen who intrude on the process. Mamet adores movies. He writes with admiration of Howard Hawks, Stanley Kubrick, and Sidney Lumet, and with something just short of ardor of the great stars, including Myrna Loy and Frances Farmer. He is not one of those writers-turned-directors who insists that a movie is sustained by its dialogue rather than its images. To the contrary, Mamet writes, “the dialogue is of as little concern to a skilled screenwriter as the paint is to the mechanic.” He is confident in his ability to direct actors (“If it’s a comedy, the answer is usually ‘throw it away quicker’; for a drama, ‘knock it off’”). And he delights in actors who don’t seem to be acting, such as Gene Hackman in the nifty noir Heist. “Time after time I’d call ‘action’ and then hear him, it seemed, continuing his informal chat with another actor, as if he hadn’t heard me,” Mamet remembers.

What Mamet cannot countenance is the godawful nonsense that is involved in trying to get a movie made. “Time and again, and to this very day, I’ve been baffled by the inability of producers, studio executives, managers, and agents to read a script,” Mamet writes. Of course, he also objects to the left-wing platitudes that now circulate in Hollywood. “The movies were never a medium for dispensing justice but rather for selling popcorn,” he notes, offering a corrective to the political correctness and social-justice sloganeering now prevalent in the industry, things that actively come into conflict with lasting art. “The Socially Conscious, I say, want to use films to ‘do good,’” he writes. “But the lesson of the dramatist is that no one acts from the desire to do wrong.”

These wise words are complemented by the canny Mamet cartoons that illustrate the book, each of which is primitively drawn — they have the sketchy quality of David Lynch’s comic strip The Angriest Dog in the World — but all of which are potent. Perhaps the best of them is a poster for a most unpromising sequel, Gandhi II. The tagline: “He’s Back! And He’s More at Peace with Himself Than Ever!!” Mamet, of course, has never gone anywhere. And, in his lifelong commitment to unvarnished candor, he’s probably always been at peace with himself.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Peter Tonguette is a contributing writer to the Washington Examiner magazine.