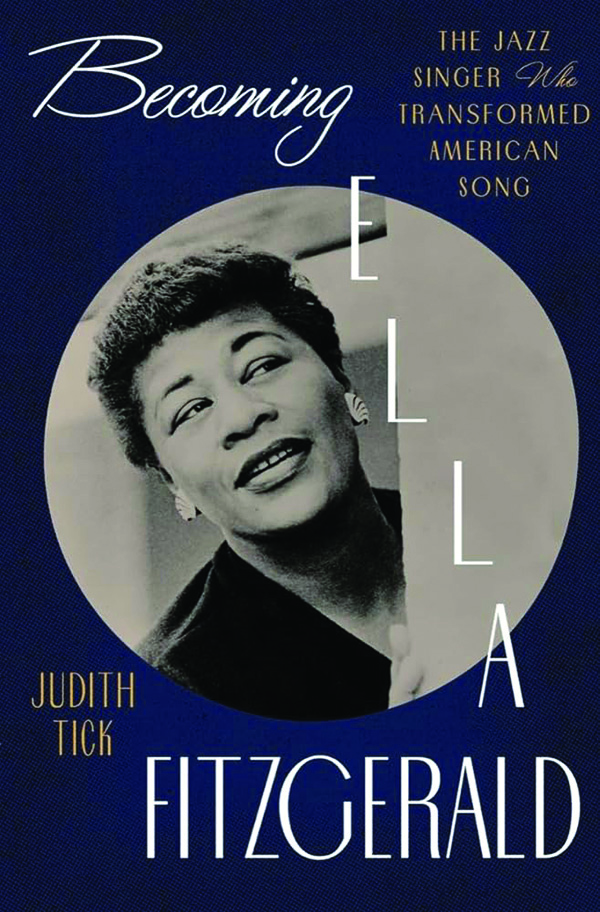

Reviewed: Becoming Ella Fitzgerald by Judith Tick

Michael Taube

A century of jazz has produced many great singers. Few have ever represented or defined the genre quite like Ella Fitzgerald, often called the “First Lady of Song” and “Lady Ella” during her long and successful career. She sang like a morning songbird. Her tone and pitch on every memorable track were perfect. Her stage presence and ability to captivate an entire room had few equals.

Judith Tick’s Becoming Ella Fitzgerald: The Jazz Singer Who Transformed American Song is a masterly examination of the virtuosa’s life and career and the first major biography written about Fitzgerald since she died in 1996. Tick, an author and professor emerita of music history at Boston’s Northeastern University, is an expert in American music and women’s history in music. Fitzgerald is deservingly placed on the mountaintop because “she treated jazz as process, not confined to this idiom or that genre. And through her own transformative quests as an artist, she changed the trajectory of American vocal jazz in this century.”

MELISSA BRODER BRINGS THE MAGIC SPARK BACK TO THE MILLENNIAL NOVEL

Fitzgerald, like many jazz legends, came from humble beginnings. She was born on April 25, 1917, in Newport News, Virginia. Her unmarried parents, Temperance “Tempie” Henry and William Fitzgerald, were described as “mulatto” in the 1920 census. Her father, a longshoreman who played the guitar, separated from her mother when she was young and never returned. Tempie became involved with Antonio Correia Borges, a “black” Portuguese immigrant, and they moved to Yonkers, New York. “Ella’s family, like most of the Black population,” Tick writes, “lived on the other side of Yonkers, a highly industrialized section, which since the mid-1800s had been drawing on immigrant labor (mainly Irish, German, and Italian) to service its factories and port shipping.” The white laborers predictably received better jobs, while black laborers “settled for the worst-paying, least-skilled jobs” and carried on.

Fitzgerald’s father wasn’t her only musically inclined parent. Tempie “influenced her daughter’s musical life” in various ways. Her mother had a “very beautiful classical voice” and preferred listening to classical music at home. They had a radio and phonograph, which was highly unusual for black families at that time. Tempie also enrolled young Ella in piano lessons and encouraged her love for dancing.

Fitzgerald’s big break came in November 1934. She signed up for an audition at the Harlem Amateur Hour. The 17-year-old apparently developed “stage fright,” according to Tick, “turning her legs and feet to stone.” Fighting off nerves and trepidation, she chose Hoagy Carmichael and Sammy Lerner’s “Judy” for her performance. It was a “rhythm song that had lighthearted lyrics and a danceable tempo,” the perfect choice for a “song-and-dance girl” who excelled at both disciplines. In front of the famed Apollo Theater, which included jazz legend Benny Carter, the night’s music director, she won the competition. The young jazz princess was on her way to becoming a queen.

Becoming Ella Fitzgerald focuses on her incredible rise to fame and fortune over a very short period. She was introduced to jazz drummer and band leader Chick Webb and soon held a “viable position” as lead singer for his popular orchestra. Her recording career began in 1935, thanks to Webb’s insistence that New York’s Decca studio take her on, and she showcased her love for jazz pianist Fats Waller’s music with renditions of “Love and Kisses” and “Rhythm and Romance.” Another jazz pianist, Teddy Wilson, trusted her to replace legendary jazz singer Billie Holiday for a 1936 performance, which exemplified “her growing reputation” in the industry.

Only two years into Fitzgerald’s budding career, the highly respected Metronome “All Star Band” 1936 poll ranked her and Webb “highest among Black musicians in their respective categories.” Fitzgerald was tied with Mildred Bailey in second place, just behind “pretty Helen Ward.” While Lady Ella wasn’t a natural beauty like Ward or Lena Horne, her voice was undeniable.

This isn’t to say Fitzgerald didn’t have several admirers within the ranks of musical royalty. Her second marriage was to the brilliant jazz double bassist Ray Brown. They originally met while working together for jazz legend Dizzy Gillespie’s band. They fell in love at the end of a 1947 tour. Brown was fired, which he “attributed to his relationship with Ella,” but they ended up in wedded bliss and had one child, Ray Brown Jr. Their marriage fell apart in 1953 due to the pressures of working, recording, and building their separate careers, but they continued to collaborate and perform together.

Tick’s extensive analysis of Fitzgerald helping transform the American song is exemplary. The starting point was her 1938 recording of the 19th-century nursery rhyme “A-Tisket, A-Tasket” with the Chick Webb Orchestra. The song, which included lyrics she co-wrote with arranger Al Feldman, brought her “success of unprecedented magnitude” and remains a jazz standard.

There’s also Fitzgerald’s famous Song Book series for Verve Records. She recorded eight albums between 1956 and 1964 of the magnificent works of Cole Porter, Duke Ellington, George and Ira Gershwin, and others. “Closing her ears to precedent” with the first Song Book related to Porter, she “found a third way that she called ‘a different style’ and that we might characterize as curatorial: self-imposed simplicity.” It was a style she employed for much of her brilliant decadeslong career when recording or performing with a litany of equally talented musicians such as Louis Armstrong, Oscar Peterson, and Frank Sinatra.

Fitzgerald was a tour de force as a singer. She connected with audiences with her powerful voice, natural charisma, voluminous musical repertoire, and support for civil rights and women’s rights. “So many people ‘loved Ella’ in different ways,” Tick aptly noted. From the upper crust to the simple Pullman porter who “realized she was a passenger on his train,” she was their singer.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Michael Taube, a columnist for four publications (Troy Media, Loonie Politics, National Post, and Epoch Times), was a speechwriter for former Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper.