Elf at 20

Titus Techera

When he wrote A Christmas Carol in 1843, Charles Dickens invented the Christmas fairy tale, setting the pattern for stories intended to be popular and thus help people see the faith that guides them at their best. But just as the Santa mythology developed from its own times and places, fairy tales from St. Nick to Charlie Brown are also a form of criticism of their own times — and a plea: Christmas is constantly in danger in our times. The tale is meant to diagnose and treat a problem in our modern societies and lives. In the 21st century, in which the Christmas fairy tale is too easily confused for the Christmas special, we still need and still tell these tales. One offering that doesn’t seem worth taking all that seriously has emerged as the great modern text of the season: Elf, which had its 20th anniversary in November.

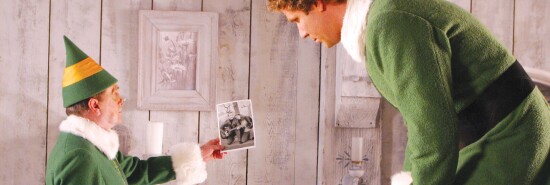

Directed by Jon Favreau and starring Will Ferrell, the movie made more than $224 million globally in 2003, so it’s safe to say it was well beloved. But it’s been in the two decades since that it emerged as a Christmas classic with staying power, something to rewatch next to It’s a Wonderful Life or before reading ’Twas the Night Before Christmas, not just a one-year hit. Elf starts with a fairy tale conceit that mixes comedy and heartbreak, as most of our Christmas stories do: a baby in an orphanage playfully stealing into Santa’s gift bag. He ends up at the North Pole, a magical place where he’s raised by Papa Elf (Bob Newhart, delightful as ever). But once he grows up to become Will Ferrell, he simply can’t fit. He’s too clumsy for the precise work elves do — and too human. He cannot be reduced to a certain skill or work. So he’s kicked out of his candy paradise, innocent like a pampered childhood, and thrust into 21st-century America.

TRAVEL TUESDAY 2023: EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT THE TRAVEL INDUSTRY’S BLACK FRIDAY

It almost seems a mistake to call Buddy an elf, but I suppose it sounds better than a boy in a man’s body, an orphan looking for his father. But look on the bright side: Buddy shares the elves’ belief in Santa, and there is something hilarious in his shock and delight at everything he sees in New York. There’s a lot of slapstick comedy, a lost art. Buddy will lose his innocence, of course, but he will also persuade people to shed their cynicism.

James Caan plays Walter, the father Buddy is looking for, as well as the cynic whose heart must be melted. Walter is a kind of Scrooge, a man who puts his business above his family. But he does so for all-American reasons. His business is failing, he is desperately trying to save it, and he cannot bring himself to think of himself as possibly failing to provide for his family. There’s worse yet. His cynicism about the business of publishing stories is threatening his soul rather than humanizing him. After all, if stories are just entertainment, belief is cheap. Like Scrooge, Walter is poorer than all the people he looks down on. He cannot really be wealthy without feeling secure, and that requires all the trappings of the celebrations.

This brings us to Santa (played wonderfully by Ed Asner). In modern America, Santa is not all-powerful, though we’re ever more prosperous. In fact, Santa is growing weaker despite his great craft, which allows him to achieve the impossible when it comes to making gifts. Santa’s sleigh runs on belief, not just tech, so we cannot get our gifts precisely because getting what we want has made us arrogant. Material plenty makes ingrates in a society that can’t reflect on itself. Santa, therefore, needs Buddy if he is to succeed in moving our hearts. We don’t want to accept that we need gifts, that we are needy. We just buy them at the mall. And that’s where Buddy goes to work, for Gimbels, trying to turn commerce into something spiritual and loving.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Elf was so successful because it reminded people about Dickens’s spirit of Christmas, the spirit in which gifts are offered. In comic terms, we see it made into goofy slapstick by the way Buddy forgets himself. In Buddy’s naivety and silliness, we see that he is not an adult. But in a way, he’s not a child, either. He’s not selfish. Through him, Elf offers us the adult correlative of the childish problem of believing in Santa. But here, the movie begins to stumble. It aims for the Romantic solution, caroling, since singing together means we all share the same thing in our hearts, but all it has to offer is Santa Claus is coming to town. This may lull loneliness and individualism but won’t fix anything.

That’s really what Elf is all about, revealing the sickness of soul Tocqueville called individualism — an inability to care about anything or anyone beyond the smallest, most concentrated circle of family and friends, isolating oneself from a society of strangers. The movie is seriously saying Christmas will save the American family, if only anyone saved Christmas first. It’s also seriously saying that if the family is only about itself, it cannot survive our modern predicament.

Titus Techera is the executive director of the American Cinema Foundation and a cultural critic.