How US and Israeli interests divide against Hezbollah

Tom Rogan

Video Embed

The Lebanese Hezbollah is escalating its attacks against northern Israel. Reports suggest that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is under pressure from his Cabinet and military advisers to respond to these attacks more forcefully. Considering the impact Hezbollah is having on Israeli settlements and military personnel, it is likely in Israel’s interest to ramp up its response.

But is it in the U.S. interest that Israel do so?

SPEAKER JOHNSON-ALIGNED GROUPS BRING IN $16 MILLION IN 10 DAYS

The Biden administration understandably wants to avoid being directly sucked into this conflict. But as skirmishes between Israel and Hezbollah escalate, so also does the risk of a war that involves the United States. This is not a hypothetical concern. The U.S. has deployed two aircraft carrier strike groups, a Marine expeditionary unit, and Air Force fighter/bomber squadrons to deter Hezbollah and Iran.

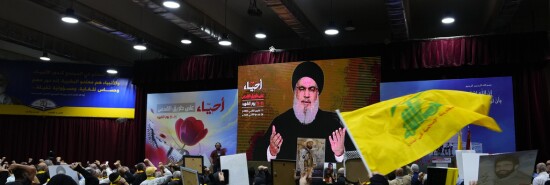

But should he choose to employ them, Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah’s missile forces and infantry units could put extraordinary pressure on Israel — far more pressure than Israel is currently suffering from Hezbollah. In that scenario, the U.S. might need to intervene to help defend Israel. The risk of the U.S. needing to become involved would be especially significant were Iran to launch ballistic missiles at Israel.

That said, the U.S. tolerance for Hezbollah’s attacks on Israel is obviously greater than Israel’s tolerance for those attacks. Already fighting Hezbollah, Israel would probably now welcome U.S. military action against the group. In such a scenario, after all, Israel obviously wouldn’t share U.S. concerns over its national interests being diminished by entering the conflict. Put another way, where Israeli national interests center on more effectively deterring Hezbollah even at the risk of escalation, U.S. national interests center on Israel’s toleration of Hezbollah escalation — tolerance, that is to say, rather than Israeli actions that risk drawing the U.S. into the conflict.

There’s another complication, namely that the U.S. also needs Israeli retaliation to be sufficient to deter Hezbollah from escalating with effective impunity. Were Hezbollah to underestimate Israeli or U.S. tolerance for escalation, war would become more likely regardless of U.S. concerns.

At present, it appears that Iran and Hezbollah do not want an escalation to full-scale war. But those calculations may change as Israel’s campaign against Hamas in Gaza continues. By responding hesitantly to Iranian proxy attacks on U.S. forces in Iraq and Syria, the U.S. risks fueling Iran’s belief that it can escalate without suffering significant counterforce. It is crucial, then, that the U.S. ramp up its retaliatory action when U.S. forces are attacked — though, as with the Hezbollah concern, not so significantly as to precipitate escalation (a hard balancing act, indeed). But it is also understandable that the U.S. and Israel will disagree over how Israel should respond to Hezbollah.