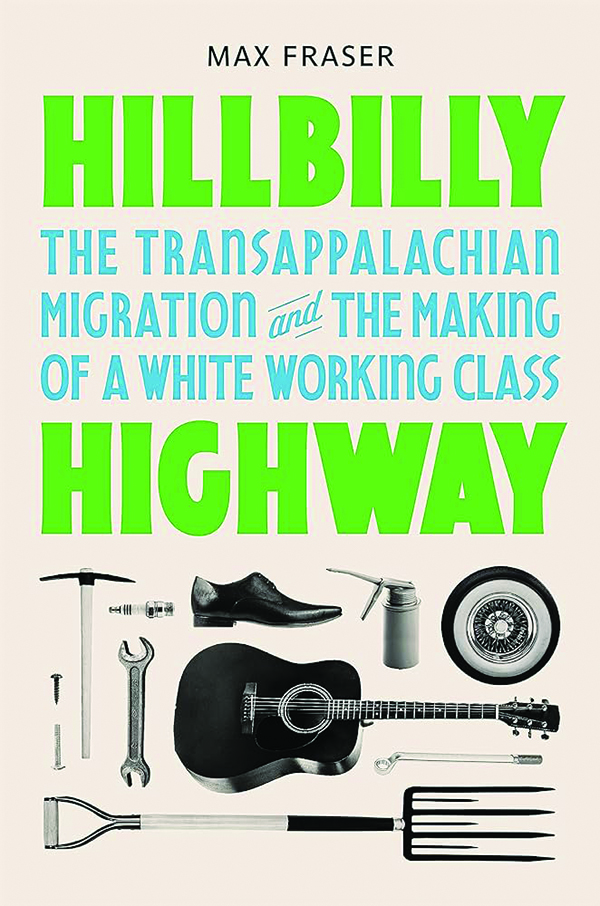

Country roads took them home

Michael M. Rosen

When the celebrated country musician Hank Williams died on New Year’s Day in 1953 in a car on his way to a performance in Canton, Ohio, he had been traveling from Charleston, West Virginia, on U.S. Route 19, one of a series of north-south arteries that had conveyed millions of struggling Southern white people from Appalachia to new lives in the industrial Upper Midwest. This “Hillbilly Highway,” as historian Max Fraser calls it, was a dense network of interstate roads that couriered the job-seekers northward. It played a pivotal role in facilitating one of the most consequential migrations in American history.

“Over the first three-quarters of the twentieth century,” Fraser writes, “somewhere around eight million poor white southerners — perhaps even more — left economically marginal parts of the southern countryside and traveled north in search of work.” The vast majority of these migrants, who hailed from the Mississippi Delta to the Appalachian foothills and everywhere in between, settled in the big industrial cities surrounding the Great Lakes. In Hillbilly Highway, he seeks to uncover the Southern white exodus to the same degree that the contemporaneous and much more carefully studied Black Great Migration and Dust Bowl departure have been described. In short, he seeks “to redeem the hillbilly highway from the dustbin of history.”

SEPARATING THE ART FROM THE IDEOLOGIST IN KILLERS OF THE FLOWER MOON

The white migration stemmed from an agrarian world turned upside down by industrialization, which saw less labor needed even as there were more people around to serve as laborers. As the Department of Agriculture bluntly put it in 1935, the South suffered from “an excess of population in relation to the economic opportunities to be found there.” Sharecroppers from Kentucky to Mississippi to Arkansas found themselves falling far behind their countrymen, even as their birth rates increased in relative terms. The “decomposition of the traditional rural social arrangements of the Upper South, a multifaceted, regionwide, and decadeslong process,” included declining land value and physical space for farming, as well as diminished health outcomes and the development of a mechanized economy.

Yet the New Deal policies designed to alleviate grinding Southern poverty reinforced the trends causing it. For instance, the Tennessee Valley Authority hastened the region’s transition from farming to resource extraction, rendering many coal-mining areas uninhabitable and expressly encouraging struggling migrants to relocate. And as more efficient techniques, such as strip mining, shrunk the pot of available jobs, the exodus accelerated.

Roads such as U.S. Routes 19, 23, 45, and 127, as well as, eventually, Interstates 55 and 75, bore itinerants northward across the Ohio River. They streamed in one direction, conveyed by a flotilla of bus lines and “taxis” (glorified station wagons), businesses that themselves were the products of enterprising former Southerners who had sojourned above the Mason-Dixon Line a generation earlier. Of these migrants, some were single men, and others traveled back and forth seasonally, but most were families. And most remained at their destinations for good.

Most of the new arrivals filled industrial positions in factory towns like Anderson, Indiana; Flint, Michigan; and Akron, Ohio. One automotive industry veteran said that Chevrolet’s Flint facility had by the 1930s become “85% hillbilly.” Companies like Goodyear even advertised in newspapers in West Virginia, seeking to lure workers northward, angling to pay new hires lower-than-market wages.

Yet this plan largely backfired: Fraser documents just how important Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia natives proved in the successful efforts to unionize automobile factories at all levels of the supply chain. Southern migrants played pivotal roles in the formation of the CIO and the transformation of the United Auto Workers into an industrial powerhouse in its own right.

Still, migrants struggled in ways large and small. The same low standards of living that rendered hillbillies “widely sought-after recruits by northern employers” also made them “widely despised by the urban workers they were hired to work alongside (or in place of).” Their distinctive accents, wardrobes, faith traditions, and pastimes came to be regarded as lower-class by the northern natives they encountered. Fraser quotes business leaders at the time referring to them as “incapable, stupid — just a crummy lot, biologically inferior,” and argues they were perceived as “a desperate and menacing hillbilly lumpenproletariat.”

Many migrants settled into distinctive, downscale, overcrowded neighborhoods in Chicago, Indianapolis, and Cleveland, urban ghettos filled with “Southern mountaineers” or “Appalachia people,” as they became known. Muncie, Indiana, reported poverty rates of 20% to 35% in the census tracts most heavily inhabited by Southern newcomers, three or four times the rate of other parts of the city. “Hillbilly taverns,” the loci of drunken and disorderly conduct, and storefront churches, featuring lively musical services, became the hallmark establishments of these neighborhoods, which featured huge rates of lead poisoning, tuberculosis, educational shortcomings, and other maladies. Following World War II, the Southern Baptists would blossom into the fastest-growing Protestant denomination in Ohio. In The Other America, Michael Harrington’s famous 1962 study of postwar poverty, Harrington argued that “the backwoods has completely unfitted them for urban life.”

From a cultural perspective, the Southern migrants left an important legacy in the form of country music. “Many mill workers,” the country music historian Bill C. Malone observed, “brought fiddles, banjos, and other stringed instruments when they relocated from their rural homes.” The genre proliferated in the 1960s, with country radio stations multiplying threefold nationwide.

Fraser’s occasional quasi-Marxist jargon can grate on the nerves, his detour into the political campaigns of George Wallace is incongruous, and the book would have benefited from exploring the reverse migration to the New South characterizing the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Hillbilly Highway is an important look at what has been a blind spot in the cultural and socioeconomic history of the United States, the northbound exodus of poor Southerners, a subject that, once illuminated, casts light on the entire cultural, racial, and economic geography of modern American history. This was a migration that moved the American spirit. As Hank Williams crooned, “When the Lord made me, he made a ramblin’ man.”

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Michael M. Rosen is an attorney and writer in Israel and a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.