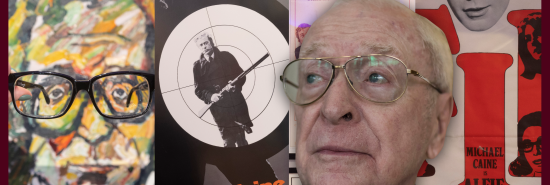

Michael Caine blew the bloody doors off

Alexander Larman

In the Nicolas Cage film The Weather Man (2005), there is a moment toward the end when Michael Caine’s character, a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist and Cage’s father, is given a living funeral to mark his imminent death from lymphoma. The actor may feel as if he’s currently living out a real-life version of the scene, so fulsome have the tributes been after he announced his retirement from acting during an interview with the BBC on Oct. 14 about his latest film, The Great Escaper. “I keep saying I’m going to retire,” Caine said. “Well, I am now. I’ve figured, I’ve had a picture where I’ve played the lead and had incredible reviews. … What am I going to do that will beat this?”

Caine has flirted with quitting the game in the past. The actor said in 2017 that “the movies retire you. You don’t retire from the movies. You don’t get a script or the script’s crap or the money’s no good and you say, ‘I’d rather stay home and watch TV.’” There have been several films in the last couple of decades of Caine’s career that give the impression of being signed up to virtually at random: Even the most committed of his admirers might hesitate before wasting two hours on The Last Witch Hunter (2015), Medieval (2022) or Now You See Me 2 (2016).

HOW THE AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION IS CENSORING CLARITY

Nonetheless, thanks in large part to a working partnership with Christopher Nolan that began in 2005 with Batman Begins and lasted until Tenet (2020), Caine stepped into the position of a cinematic eminence grise with aplomb. Over that period, he was excellent in Interstellar (2014) as a high-ranking NASA scientist, convincingly played against type as a composer in Paolo Sorrentino’s Youth (2015), and was a menacing presence in the British vigilante thriller Harry Brown (2009). One of the most vigorously conservative pictures released this millennium, Harry Brown featured Caine as an army veteran single-handedly cleaning up his London housing estate by killing off members of a violent gang who have terrorized it. He saw acting in the film as a public service of sorts, saying on release, “You’ve got to do something about gang violence because if you don’t, private citizens will.”

Yet when the obituaries of Caine are finally written, it will be his great roles of the ’60s that take up the most energy and space in the eulogies, from his star-making appearance in Zulu (1964) to his smart and self-aware comic parts in Alfie (1966) and The Italian Job (1968). Like his friend Sean Connery, Caine came to prominence at a time when having a working-class accent was not the bar to success in the notoriously snobbish British film industry that it would have been a decade before. And he paved the way for younger actors from similar backgrounds to come through, including Gary Oldman, Tim Roth, and Ray Winstone.

By his own admission, once he had achieved fame, Caine took many roles for the money rather than the prestige. He dipped to his career nadir with a supporting part in the diabolical Jaws: The Revenge (1987), although he managed to rescue his reputation by quipping, “I have never seen the film, but by all accounts it was terrible. However, I have seen the house that it built, and it is terrific.” Yet he won an Oscar for appearing in Woody Allen’s Hannah and Her Sisters (1986). And amid the artistic detritus, he was excellent in everything from Mona Lisa (1986) to Dirty Rotten Scoundrels (1988). In 2000, there was a second Oscar for his avuncular appearance in the John Irving adaptation The Cider House Rules (1999). Never mind that his kindly Maine doctor seemed to have arrived straight off the ship from England that day — it was a popular award that confirmed that the then-67-year-old Caine was a Hollywood fixture.

As for the final act of his career, in October 2021, Caine said, “There haven’t been any offers honestly for two years because nobody’s been making any movies I want to do. Also, I’m 88. There’s not exactly scripts pouring out with a leading man that’s 88, you know?” The Great Escaper, in which he co-stars opposite the late Glenda Jackson, belies this. The picture, which features Caine as a World War II veteran who leaves his assisted living home in Britain’s South Coast to head to Normandy to attend the 70th-anniversary celebrations for D-Day, has won acclaim from British critics, mainly for Caine’s typically charismatic and humorous performance. If this is his swansong, it’s a fine way to go.

Michael Caine’s exit is thus a lot like he is: unfussy and unremarkable, so superlatively so that it deserves to be fussed over and remarked upon. The last chapter of Caine’s career is not quite like that of Ian McKellen, Helen Mirren, or Patrick Stewart, longtime stars of the Hollywood screen and London stage whose talent and gravitas hit their highest peaks in old age. Yet Caine’s retirement distinguishes him from fellow elder statesmen and former co-stars Jack Nicholson and Gene Hackman, both of whom quit acting after the offers and talent withered. Neither of their respective final films, the romantic comedy How Do You Know (2010) or the political satire Welcome To Mooseport (2004), would be considered among their best. Sean Connery, in a more extreme case, had such a notoriously unpleasant experience filming the superhero flop The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (2003) that he never appeared in another live-action film afterward.

And there are other younger high-profile actors who have quietly vanished from the profession, including David Caruso, who is now an art dealer, and the legendary Daniel Day-Lewis, who described his decision to retire as a “compulsion” after a career that included long hiatuses and suggestions of mental instability caused by his take-no-prisoners Method acting, including famously leaving a London production of Hamlet in 1989 after supposedly seeing his father’s ghost onstage.

Caine has never been so introverted an actor, offering cheerfully candid interviews in which he has discussed everything from his political conservatism (he was one of the few British actors who openly supported Brexit in 2016) to his wide array of famous friends. As he mournfully admits, most of these contemporaries, from Connery to Sinatra, have now died, leaving him as the last man standing. He may yet be tempted back for a final cameo, even if his health has declined. But if this really is the end of a remarkable career, then the man formerly known as Maurice Micklewhite deserves the warmest of applause as he steps out of the spotlight for the final time.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Alexander Larman is the author of, most recently, The Windsors at War and an editor at the Spectator World.