The real modern China

Sean Durns

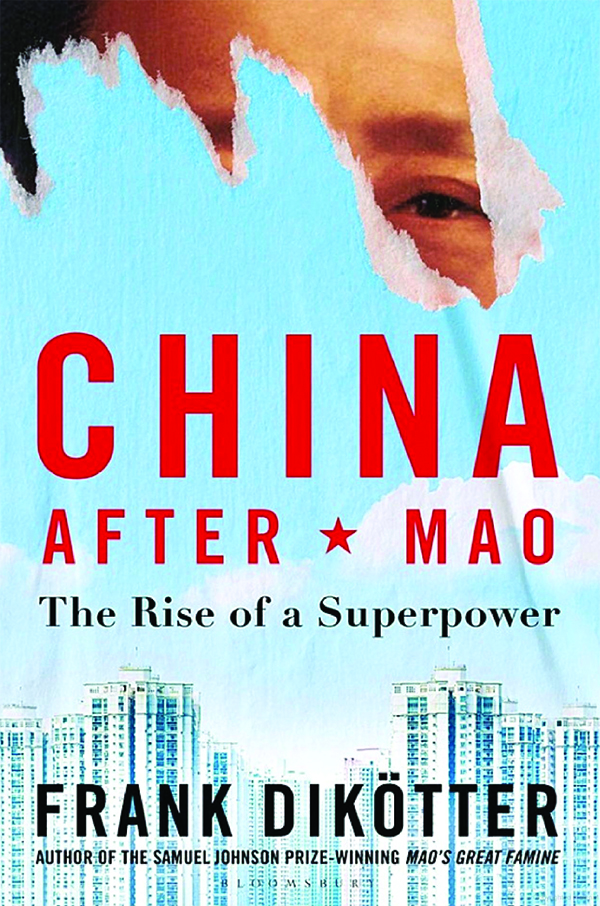

The rise of modern China is arguably the greatest and most consequential story of our time. And as Frank Dikotter highlights in his new book, China After Mao: The Rise of a Superpower, it is a tale of greed, violence, and inequality. The great historian of the Mao era has now moved to our own time, and he comes to the present day with a warning. By banking on the Chinese Communist Party somehow liberalizing, the West has made one of the gravest miscalculations in modern history. One would have to go back to the policy of appeasement in the 1930s to find something similar — and even then, it must be noted Communist China today is vastly more powerful economically and technologically than either Imperial Japan or Nazi Germany. As Dikotter ably documents, the largest police state in world history, increasingly bellicose, stands on the bones of its people. And we can no longer afford to pretend otherwise.

Dikotter is a Dutch historian who specializes in modern China. He is perhaps best known for authoring The People’s Trilogy, a three-volume, award-winning series on Communist China. The University of Hong Kong professor used original archival sources to examine the impact of communism during the three decades after the Chinese Communist Party seized power in 1949.

By using new sources, Dikotter chronicled the horrors induced by the CCP and its leader, Mao Zedong, including the Great Leap Forward, a government-created famine that claimed the lives of an estimated 45 million people. The widely lauded series shined a light on the cruelty and inhumanity of Mao and the system that he imposed on one of the world’s most populous nations.

That system, Dikotter makes clear in his new book, has endured. Indeed, it has grown, fed in part by the illusions and appetites of insatiable outsiders who, time and again, have pretended that the Chinese Communist Party is something that it is not.

Until recently, Western pundits and policymakers were bullish about Beijing, believing that economic liberalization would lead to political liberalization. The autocracy practiced by Mao and his acolytes would be a thing of the past. It was only a matter of time, it was thought and often said, until China would liberalize. Trade was one way to achieve that objective, and everyone would benefit. Sure, the CCP wasn’t perfect, but with the right amount of patience and finesse, the future would be one of shared cooperation between China and the U.S.-led liberal international order.

In the United States, such thinking was bipartisan and embraced by everyone from Henry Kissinger to New York Times columnist Nick Kristof, who, in a 2013 column, predicted that newly installed Chinese Communist Party Secretary Xi Jinping would “spearhead a resurgence of economic reform, and probably some political easing as well.” Under Xi’s “watch,” Kristof predicted, “Mao’s body will be hauled out of Tiananmen Square,” and famed dissident Liu Xiaobo “will be released from prison.”

Such illusions are endemic to China watchers — in part because, as Dikotter notes, a lack of reliable information forces them to speculate. And speculation is often accompanied by what the late columnist Charles Krauthammer termed the “mirror image fallacy,” the idea that others share our motivations and would act as we act. But as James Palmer, one of the more thoughtful China analysts, has recently observed: “Nobody knows anything about China: including the Chinese government.”

“Where China is concerned,” Dikotter writes, “we don’t even know what we don’t know.” Understanding China accurately is impossible, not least because of the country’s daunting size, currently some 1.4 billion people, but also because of government that exerts tight control. Even archival records themselves can often be misleading. As Dikotter points out, it wasn’t, and presumably still isn’t, unusual for local government officials to mislead and lie, sometimes falsifying reports to top party leaders for their own varied reasons, from obtaining funds to escaping punishment.

For his previous books, Dikotter spent a decade scouring the country for party records, sometimes happening upon secret minutes of top party meetings, investigations into mass murder, confidential opinion surveys, and even letters of complaint from ordinary people. Since then, many of the documents have been reclassified. For China After Mao, he used roughly 600 documents from a dozen municipal and provincial sources, as well as newspaper reports and unpublished memoirs. The conclusion that emerges is surprisingly clear: The Chinese Communist Party is incapable of reform and political liberalization. What is more, it always rejected the very idea of opening up.

Dikotter’s chapter on the rise of Deng Xiaoping, the man who succeeded Mao and is often heralded in the West as a reformer responsible for “ushering in a new age,” as the Washington Post put it, is titled “From One Dictator to Another.” Deng could travel to the U.S. and pose, as he did in 1979, smiling in a 10-gallon cowboy hat. But he was no liberal. Indeed, like his colleagues and sometimes rivals, Deng both hated and feared the U.S. As Zhao Ziyang, another CCP apparatchik beloved by the West, told the Party Congress in October 1987: “We will never copy the separation of powers and the multiparty system of the West.”

Seemingly this would present a contradiction for China and the CCP, which, popular belief holds, has pursued economic liberalization. Yet, on page after page, Dikotter punctures this myth. Rather, “what we have witnessed so far is merely tinkering with a planned economy.” The CCP, he notes, still insists on having Five Year Plans just like its Leninist forefather, and “more to the point, since 1976 the party has continued to retain ownership of all industry and most large enterprises … in classic Marxist parlance, the ‘means of production’ remain in the hands of the party.”

This leads to another key takeaway from Dikotter’s book: China’s economy, far from being infallible and omnipotent, is a basket case. Some of the anecdotes and information that the historian relays are truly jaw-dropping. “Most of the country’s leaders,” Dikotter notes, “do not understand basic economics, focusing almost obsessively on one single figure, growth, often at the expense of development. The result is waste on a staggering scale.” In some respects, things have changed remarkably little since Mao’s Great Leap Forward, in which the regime’s irrational obsessions murdered millions and set the country so far back economically that by 1970, factories even had trouble manufacturing buttons. Given China’s size and role in world affairs, this isn’t something that can be overlooked. As historian Stephen Kotkin recently pointed out: “We’ve never had an economy this large run by a political system this opaque.”

Dikotter’s argument is bolstered with economic figures, yet the book is far from dry. A skilled writer, Dikotter is accessible to both expert and lay readers alike. Part of this is also due to Dikotter’s commendable focus on the chief victims of the Chinese Communist Party: the Chinese people themselves. The late historian Robert Conquest wrote groundbreaking books on the Soviet Union, which, by focusing on the suffering of those living under Soviet rule, were revisionist and prescient. Dikotter has done the same for China.

Sean Durns is a Washington, D.C., based foreign affairs analyst.