Israel’s war of atonement, 50 years on

Sean Durns

“War,” the late historian Barbara Tuchman once observed, “is the unfolding of miscalculations.” Fifty years ago, a war born of miscalculations and hubris erupted in the Middle East. While it was neither the first nor the last war in the region, it ranks among the most consequential. The Yom Kippur War changed both Israel and the broader Middle East forever, its aftereffects still visible today.

“Until the Yom Kippur War in 1973, until then, Israel didn’t have a chance but to fight for her life,” the late Israeli politician Shimon Peres observed. “We were attacked five times, outgunned, outnumbered, on a small piece of land, and our main challenge was to remain alive.” That challenge was particularly acute in October 1973, when Israel was caught flat-footed by a combined attack from the armies of Anwar Sadat’s Egypt and Hafez Assad’s Syria. The United States would alternately constrain and aid Israel in its defense.

ISRAEL WAR: HAMAS SURPRISED AND ‘WORRIED’ BY HOW SUCCESSFUL ATTACK TWO YEARS IN THE MAKING WAS

Indeed, the modern U.S.-Israel relationship can largely be traced back to that conflict half a century ago. So, too, can the Jewish state’s improved relations with many of its Arab neighbors. The war’s aftermath led to the first recognition of Israel by Arab states — an event that itself spawned assassination and modern incarnations of terrorism.

For Israel, the war would change everything, upending the political landscape and leaving behind bad blood and recriminations that echo to this day. In many ways, it remains among the most controversial of the many wars that Israel has fought in its 75-year existence, and for good reason.

On the war’s eve, Israel was a country transformed. The Jewish state’s surprise victory in the 1967 Six-Day War, in which Israel defeated the combined armies of its Arab opponents in less than a week, significantly changed the nation’s territorial borders. Almost overnight, Israel quadrupled in size. A country that on war’s eve had dug mass graves in anticipation of another Holocaust not only survived but succeeded beyond its wildest dreams. Jerusalem had been reunified, and Israel found itself with significant holdings in the Golan in the north and the Sinai in the south.

The conventional narrative has it that Israel’s miraculous victory in 1967 made the country complacent. By October 1973, the argument goes, drunk off its status as a new military superpower, the country’s leaders overlooked peace overtures from Egypt, viewing its Arab opponents as vastly inferior. But this is too simple by far.

In fact, the origins of the 1973 Yom Kippur War can be traced back to Israel’s re-creation in 1948. Arab states had rejected a United Nations partition plan to create two states, one Jewish and another Arab, out of the British Mandate for Palestine, which itself was created from the ashes of the Ottoman Empire. Declining both peace and the chance to create a sovereign Palestinian Arab state, Arab armies attacked the nascent Jewish nation, seeking its destruction. They failed. Israel survived, but only barely. Led by Egypt, the preeminent Arab superpower of the time, the Arab Middle East refused to recognize Israel and continued with its unceasing attempts to vanquish the country and its people.

Although Israel’s critics would later claim that peace was possible after the Six-Day War, alleging that Israeli leaders missed numerous peace overtures, the abundance of evidence suggests otherwise. After that conflict, 13 Arab states gathered at the Sudanese city of Khartoum and issued the infamous “three No’s: no peace with Israel, no negotiations with Israel, and no recognition of Israel.” By contrast, Israeli Defense Minister Moshe Dayan said that Jerusalem was “waiting for a phone call” from Arab leaders. But the line never rang.

Instead, Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser launched what Israelis would call the “War of Attrition.” That low-intensity conflict, characterized by frequent artillery shelling, ground on for years. Increasingly, the Egyptians were armed, equipped, and trained by a Soviet Union that was determined to destroy Israel and turn the Middle East into a Cold War battlefield. The war was a “major proving ground for the military equipment of the two superpowers,” Israeli diplomat Chaim Herzog noted.

But as Uri Kaufman highlighted in his new book on the Yom Kippur War, “the Egyptians might as well have trained their guns upon themselves.” Nasser and his generals failed to conduct “even basic planning.” Suffering terrible losses, the Egyptians would come to call the conflict the “War of Bloodletting.”

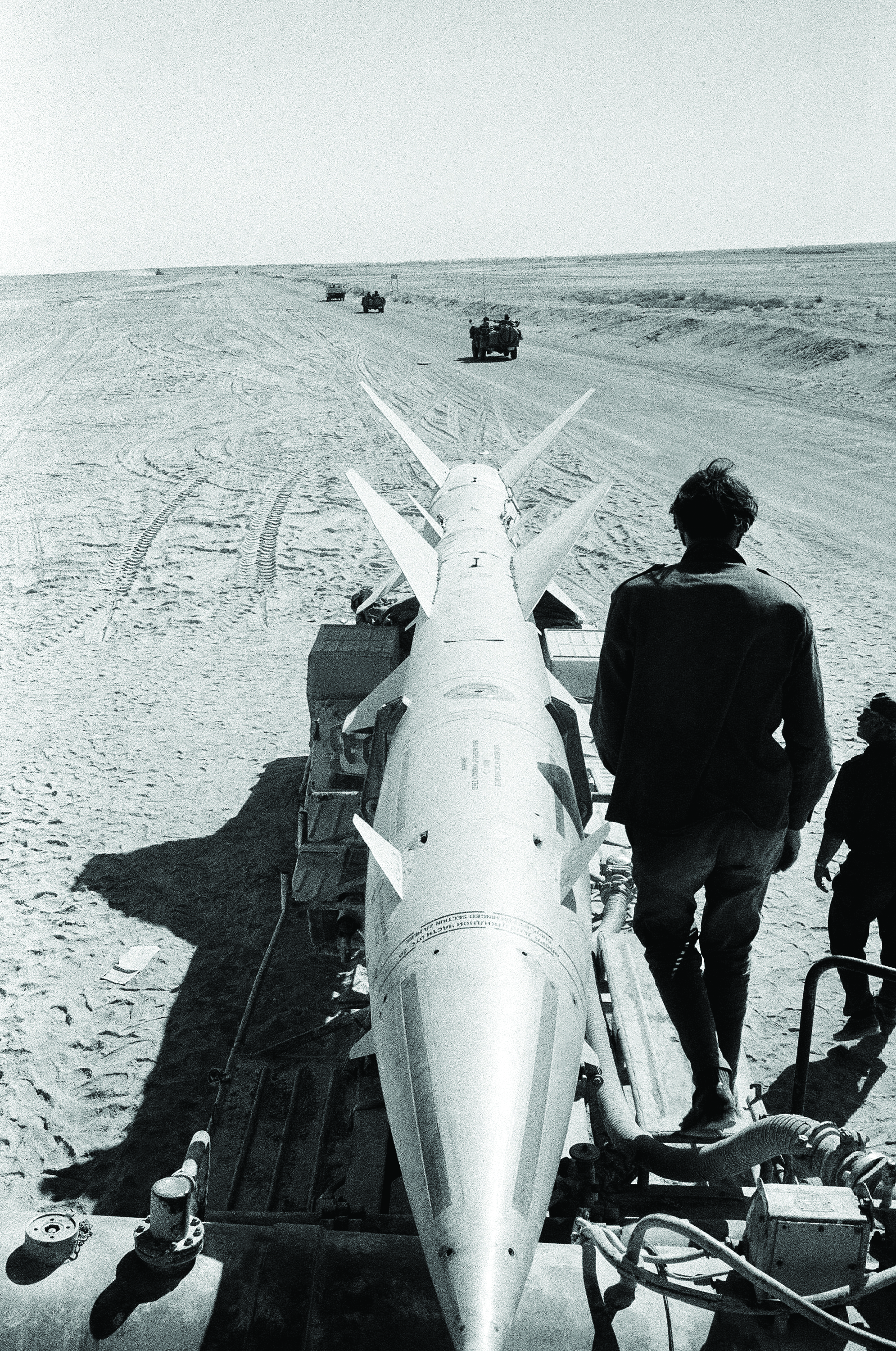

The U.S. was reluctant to intervene. Pushed by an increasingly desperate Nasser, the Soviets had no such qualms. After Nasser made a secret trip to Moscow, the Soviets sent thousands of military advisers and advanced fighter planes. By 1970, the Soviet Union was supplying advanced surface-to-air missiles (SAM-3) that would prove devastating to Israel in the war to come. By contrast, the U.S. took steps that, if unintentionally, emboldened Egypt.

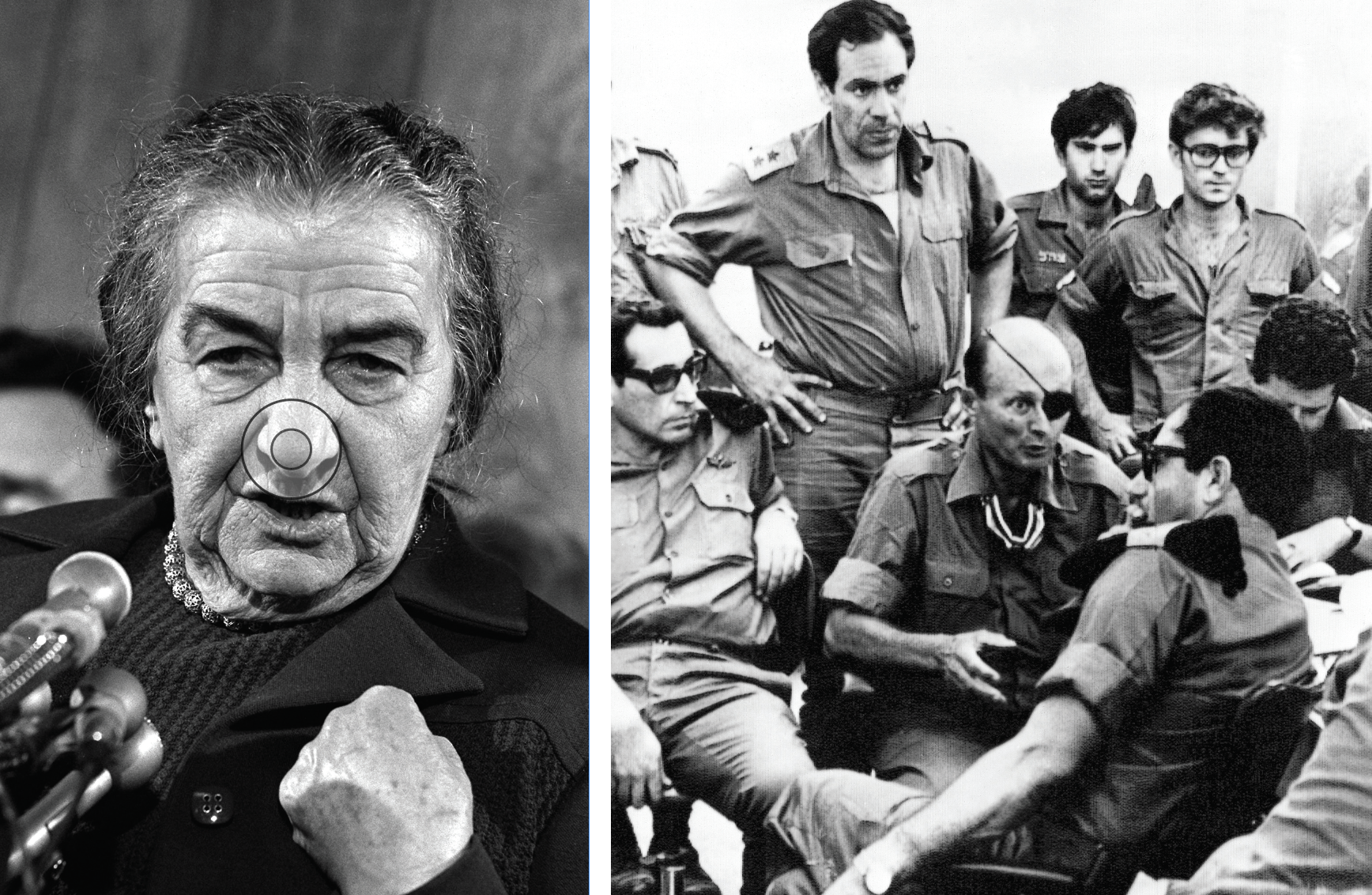

In 1970, President Richard Nixon halted arms sales to Israel. Worse still, far from preventing war, American diplomacy may have enabled it. In June 1970, U.S. Secretary of State William Rogers introduced a peace plan that included a 90-day ceasefire. Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir was loath to accept the plan, fearing that Egypt would exploit the ceasefire. The Nixon administration threatened that opposing the plan would result in a loss of future military aid. The U.S. reassured the Meir government aid would be forthcoming and that no Israeli soldier would be withdrawn from the present lines until an agreement was reached. These assurances pushed Israel’s Cabinet to support the Rogers plan.

The ceasefire began on Aug. 8, 1970. But within hours, Israeli aerial surveillance witnessed Egyptian soldiers moving Soviet SAM-2 and SAM-3 systems into place on their side, even though the agreements forbade moving military equipment into the area. As Meir biographer Francine Klagsbrun observed, “The ink had barely dried on the ceasefire agreement, and it was already being violated.”

Israel highlighted these violations. But only in September did the U.S. State Department acknowledge that violations had occurred. Yet no consequences followed. Just as Meir had predicted, Israel’s enemies had exploited the U.S.-backed agreement, taking full advantage of Washington’s naivete.

Thanks to American ineptitude, Israel’s security situation had deteriorated. But other factors proved key to the devastating war that followed. On Sept. 28, 1970, Nasser died. The handsome and charismatic Nasser had embodied Arab nationalism. For nearly two decades, Nasser led Arab opposition to Israel’s existence. His successor, Sadat, was thought to be a mere placeholder.

According to one account, Nasser had named Sadat vice president in December 1969 to enable the loyal lieutenant to earn a higher pension. Another account posits that Nasser simply believed that “it was Anwar’s turn to be vice president.” In the 18 years that he had served under Nasser, Sadat opposed him only once — and this was when Nasser suggested democratic reforms after Egypt’s 1967 defeat. As Kaufman has written, Sadat had distinguished himself “only in the degree of his fealty to Nasser.” The U.S. undersecretary of state, Elliot Richardson, cabled Washington that he expected Sadat to last no more than six weeks in office. Richardson’s boss, Henry Kissinger, privately called Sadat a “buffoon.” Nor did many Israeli officials have a higher opinion.

But Sadat would surprise everyone. Nasser had been erratic and temperamental. Sadat was cut from a different cloth. Although he lacked Nasser’s base of support, Sadat proved to be a cunning operator. Like Nasser, Sadat refused to meet with Israelis. But unlike Nasser, Sadat slowly and steadily built up conditions and showed himself able to manipulate the wily Syrian dictator Assad.

The new Egyptian ruler also recognized his own precarious situation. Sadat felt that Egypt’s deteriorating economy meant that he would have to attack Israel — and soon. Israel and the U.S. may not have known it, but in Sadat, they faced a far more capable foe. And while Sadat may have been aided by American naivete, the Israelis would also drop the ball.

Israel possessed considerable intelligence assets. The country had several top spies embedded within the Egyptian regime, among them Nasser’s own son-in-law Ashraf Marwan, code-named “Angel.” Jerusalem also had a top Egyptian army officer on its payroll whose existence wasn’t publicly revealed until 2020. As importantly, Israel also had what it referred to as “Extraordinary Measures,” highly developed electronic capabilities described by one official as “battery-powered listening devices attached to telephone and telegram branches … which allowed eavesdropping on conversations in places in Cairo.” Aman, Israel’s military intelligence, referred to these measures as its “insurance policy.” In short: Israel’s intelligence capabilities and assets were exceptional. But the analysis of the intelligence, and certain key officials, would fall short.

There were several war scares in the period between the ceasefire and October 1973. As Kaufman has noted, the unnamed Egyptian army officer had “warned of a surprise attack no fewer than six times in 1969, six times in 1971, and five more times after that in 1972.” In December 1972 and again in May 1973, both the officer and Marwan warned of an attack. Those who correctly predicted that the attacks wouldn’t occur, such as Aman Director Eli Zeira, had their reputations enhanced.

The Egyptian military added to the confusion by increasingly conducting military exercises near the border. This was a method to disguise its intentions that it had learned from its Soviet patrons.

By September 1973, alarm bells were going off. The previous month, Aman had learned that Scud missiles had arrived in Egypt — a factor that Zeira once viewed to be a necessary condition for an Egyptian attack. Now, however, he dismissed it. Israeli air force intelligence officers believed that it would take at least six months for the Egyptians to learn how to use the Scuds. They were wrong.

Zeira continued to brush off warning signs. And when Jordan’s King Hussein secretly arrived in Israel on Sept. 25, 1973, with vague warnings about a future attack, Israeli Defense Minister Moshe Dayan told Meir not to worry. On Sept. 30 and again on Oct. 2, a source told Zeira that an attack was imminent. Zeira didn’t tell Meir. And when David “Dado” Elazar, the Israel Defense Forces chief of staff, asked Zeira if he had employed the Extraordinary Measures, the Aman head lied and told him he had.

But on Oct. 4, 1973, Israeli intelligence intercepted communications showing that the families of Soviet advisers were leaving Syria. Marwan met with Zvi Zamir, the head of Mossad, Israel’s foreign intelligence agency, on Oct. 5, warning of an impending Egyptian attack.

However, the Angel’s warning still wasn’t enough to shake Dayan and Zeira from their complacency. The former still mistakenly believed that Zeira had been utilizing the Extraordinary Measures, and in an early morning meeting on Oct. 5, Dayan argued that a mere partial mobilization would suffice. The Israeli Defense Forces was composed largely of reservists. Mobilizing them was a significant economic burden. But Meir, backed by Elazar, overruled Dayan.

The prime minister didn’t think that Israel could preemptively strike as it had in the last war. “This isn’t 1967,” she lamented. “The world will never believe us.” The years of friction with the U.S. no doubt weighed on her mind. And sure enough, Kissinger beseeched Meir not to strike first.

On the afternoon of Oct. 6, Egypt attacked. The Egyptian army made steady gains, thanks in no small part to Israel’s lack of preparation. Egypt’s performance, Kaufman noted, “exceeded every expectation.” Meir was right. This wasn’t 1967.

Israel was sent reeling, suffering horrendous losses in both men and material. The Egyptians quickly crossed the Suez Canal, an act that Sadat’s generals had made sure they’d practiced no fewer than 23 times. Within 12 hours, the sole armored division in the Sinai was largely destroyed by Egypt. The Syrians also launched a coordinated attack, crossing the ceasefire lines on Israel’s northern border and punching right through the IDF.

For three days, the Arab armies made startling gains. SAM-3 proved devastating to the Israeli air force, the jewel in Israel’s defense crown. Oct. 8 “would be remembered as the darkest day in the history of the Israeli army,” Kaufman noted. “In all, Israel lost 60 tanks, more than two battalions.”

Dayan, an internationally famous general and a symbol of the Jewish state’s military prowess, had a breakdown. On several occasions, the defense minister was heard to say, “The Third Temple is in danger,” alluding to the first two temples that had been destroyed by the Assyrian and Roman armies in centuries past. The Third Temple was Israel. Dayan would ask for authorization to “begin preparations for a display of nuclear power” only to be told by Meir, in English, to “forget about it.”

After three days of heavy fighting, the Egyptian offensive was halted. Israel began to regain both the initiative and lost ground. Eventually, the IDF surrounded the Egyptian Third Army. But the Jewish state had suffered grievous losses, its equipment and munitions running perilously low. When Kissinger was told the figures, he was shocked. Israel would need a resupply.

At Nixon’s behest, the U.S. eventually initiated an arms airlift — a decision that infuriated the Arab states. However, the air supply was initially held up. Some have argued that Kissinger was responsible, with the U.S. secretary of state wanting to ensure that Israel didn’t win too decisively so a future peace with Egypt would be possible. Kissinger himself has long denied it.

Israel could have destroyed the Third Army. Fatefully, it did not do so. After nearly three weeks, the war was over. Israel had made a miraculous turnaround, ending the war with both Cairo and Damascus in its sights and with great battlefield victories. Yet Israel hardly felt like a victor.

As the Israeli historian and diplomat Michael Oren has noted, the war is remembered not for its ending but for its beginning.

Just seven years before, Israel had vanquished its opponents in mere days, ending the conflict with not only more land but a justly deserved reputation as a military powerhouse. The Yom Kippur War was quite the comedown. It was not, as Meir noted, 1967. Stunned Israelis wanted answers.

The Agranat Commission, established in the war’s wake to examine the Jewish state’s failures, blamed Zeira, among others, including IDF chief of staff Elazar, who died two years later, at age 50, of a heart attack. But it would absolve both Meir and Dayan. This conclusion proved controversial with the Israeli public, many of whom thought that their leaders had escaped blame.

Meir would soon exit office, exhausted. She never recovered from the war. Neither did the Israeli Labor Party, which had ruled since the Jewish state’s re-creation in 1948. Three years after the war’s conclusion, Menachem Begin and the Israeli Right won elections. And except for a handful of years and some unity governments, it has largely ruled ever since.

Sadat fared better, at first. In the minds of many Egyptians, the Egyptian army had redeemed itself and honor had been restored. This, and Israel’s decision not to destroy the Third Army, enabled Sadat to make peace with Israel. This event later led to an Israeli-Jordanian peace in the 1990s, as well as the Oslo peace process that created the Palestinian Authority. Sadat, however, wouldn’t live to see either. The peace that he made cost him his life, and he was assassinated in 1981 by Islamic terrorists who would soon take the place of conventional Arab armies as the biggest threat to Israel and peace in the Middle East.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Making peace with Israel was a prerequisite for moving Egypt from the Soviet to the American sphere. The Soviets had lost their most important Middle Eastern ally, a key American victory in the Cold War. And the U.S.-Israel relationship was further solidified. In the entirety of the Cold War, Israel is the sole country to have defeated two generations of Soviet-backed forces on the battlefield. American arms had been put to good use.

From the vantage point of half a century, the Yom Kippur War, with its tank battles and Soviet MiGs, seems far removed from the Islamism and asymmetrical warfare that has since engulfed the region. It belongs to another era, but it helped forge our own.

Sean Durns is a senior research analyst for CAMERA, the 65,000-member Boston-based Committee for Accuracy in Middle East Reporting and Analysis.