HBO’s Lakers comedy chronicles the rise of the Celtics

Andrew Bernard

“No f***ing way can a Lakers show end in 1984,” Jeff Pearlman, the author of the book HBO’s Winning Time: The Rise of the Lakers Dynasty is based on, posted on Twitter in August in a bid to save the show by attracting more viewers. But it did end there, thanks to HBO executives, who were also responsible for the show’s clunky name. Pearlman’s book, like the 1980s Lakers themselves, was called Showtime, but the big brains at Home Box Office could not bring themselves to name the series after their premium television network rival, Showtime. For Lakers fans watching Winning Time, the villains of the show will be those HBO executives. By canceling the show at the end of its second season, those executives have created the best show about the Lakers losing ever made.

Here I have to declare an interest: I’m a Bostonian, so ending this show with the Celtics’ 1984 NBA Championship is about the funniest way possible for me to imagine the end of a show dedicated to Magic Johnson’s “Showtime” Lakers, who went on to recover from that loss to win two championships against Larry Bird’s Celtics.

HULU SHOULD BE HAUNTED BY HOW GOOD THE OTHER BLACK GIRL COULD HAVE BEEN

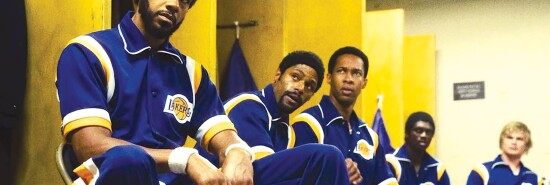

Despite the corny name, the two seasons of Winning Time were awfully enjoyable to watch. Unfortunately, one of the things that made Winning Time good is also why it’s impossible for me to imagine the series getting resurrected, namely that it has some of the best casting in television history. That begins with some of the first-time actors cast as Lakers players. Quincy Isaiah as Earvin “Magic” Johnson nails Magic’s charisma and should have a future in acting beyond this show. And unless you could get a younger Kareem Abdul-Jabbar to play himself, I don’t see how you could do better than Solomon Hughes, who, as a 6’11” former Harlem Globetrotter with a Ph.D. from the University of Georgia, must be one of the only men in America (the world?) who can plausibly depict the stature, ball skills, and intellect of one of America’s greatest philosopher-athletes.

For Lakers point guard Norm Nixon, the show’s creators effectively did find a younger version of the man himself by casting Nixon’s son, DeVaughn. Along with Sean Patrick Small as Larry Bird, all of these actors pull off the impressive feat of making the basketball not just look like professional basketball, but professional basketball as played by some of the most distinctive players ever to play the game. (A statistical example of that distinctiveness that blows my mind: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar held the NBA career scoring record for 39 years until it was broken earlier this year by LeBron James. Of Kareem’s 38,387 career points over 20 years of playing, he scored exactly one three-pointer. Fellow big-man and Laker Shaquille O’Neal also had exactly one three-pointer in his similarly long 19-year career — but with nearly 10,000 fewer total points.)

While Winning Time is undeniably a show about basketball, it ultimately has more in common with Executive Producer Adam McKay’s other ripped-from-the-headlines ensemble comedies such as The Big Short or with the office-bound baseball film Moneyball than a traditional sports film like Hoosiers. In the first episode of season two of Winning Time, when the text “White, White, White” is imposed over the screen when Larry Bird is described as a “hard-working, disciplined, all-American boy,” and the text “Black, Black, Black” when Magic Johnson is described as a “show-stopping, naturally-gifted, physical specimen,” the issue is not that McKay is inserting racial politics into the Celtics-Lakers story. The issue is that he apparently thinks he’s the first person to discover that there were racial politics in the Celtics-Lakers story. This is the larger problem with McKay and his politics explainer-infused production and direction aesthetic. It’s not that he’s left-wing — who in Hollywood isn’t? It’s that he combines an insufferable self-superiority with an inability to distinguish clever exposition from smug condescension.

But McKay, thankfully, only directed that first episode, and the series otherwise reserves his fourth wall-breaking techniques for moments that are genuinely interesting or surprising. “Yes, he really played in jeans,” the screen tells us when Larry tries out for Indiana State in work boots, jeans, and a flannel shirt and proceeds to start draining jump shots.

On racial politics, it would have been interesting to see how the show’s creators handled Larry and Magic’s off-the-court friendship that developed after they filmed a Converse sneaker ad in 1987. By each of their accounts, the relationship was enormously deepened by Magic’s HIV diagnosis in 1991.

Seen from 2023, the Celtics-Lakers rivalry of the 1980s looks less like a “Boston=racist, LA=good” caricature and more like a national attempt to achieve a color-blind ideal through the process of basketball, which culminated in Michael Jordan being arguably the most famous person in the world in the 1990s. There is, however, no shortage of perfectly good documentaries telling those stories, including HBO’s own Magic & Bird: A Courtship of Rivals or ESPN 30 for 30’s Celtics/Lakers: Best of Enemies.

What those documentaries lack, aside from the dramatic exaggerations that have caused almost everyone depicted in Winning Time to condemn the show, is John C. Reilly as Lakers owner Jerry Buss.

Is it possible to continue calling John C. Reilly a character actor? John Goodman is perhaps the only other actor alive who is so consistently good in every film and television role, comedic or dramatic, as leading man or supporting actor. Like Goodman, he’s frequently the highlight in even a bad picture. All of that is true here — Reilly even elevates Buss himself, such that we somehow like the creepy playboy bigamist who keeps a photo album of his sexual conquests.

Of the other performances, Adrien Brody’s transformation into the chain-smoking, slicked-hair Lakers coach Pat Riley of the ’80s is uncanny. Michael Chiklis, almost unrecognizable as Celtics GM Red Auerbach, chews screen and cigars. He could probably helm a Celtic Pride miniseries of his own.

Despite all of these performances, Winning Time disappointed at last year’s Emmys, garnering only a single nomination for cinematography. That cinematography got better in the second season, though some may be distracted by the sheer variety of film formats and aspect ratios the filmmakers switch between. For anyone interested in the technical aspects of filmmaking, it’s worth reading interviews with cinematographer Todd Banhazl — they really shot this thing with 8 mm, ’70s-era TV broadcast tube cameras and VHS camcorders. Likewise, I don’t know whether it was done digitally or with Lord of the Rings-style in-camera forced perspective, or both, but it’s impressive that they preserved the relative heights of all the players despite some characters being depicted by much shorter actors. Winning Time’s budget is unknown, but none of this can have been cheap.

If the creators had spent less money editing together a half dozen different types of film formats, they might have been able to pace their truncated seven-episode season that lingers at times on unresolved plotlines better before rushing through to the ultimate anticlimax of the Lakers’ defeat in the 1984 finals. And that might have saved the show from those executives at HBO, who, yes, are easy to see as the villains here. But they’re also the ones who greenlighted something as ambitious and weird and fun as Winning Time in the first place. Hopefully, that ambition survives the reorganization from HBO to MAX. Because despite the proliferation of prestige TV, they’re still the only network that makes shows like this.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Andrew Bernard is the Washington correspondent for The Algemeiner.