What Picasso thought of Abe Lincoln

Eric Felten

Video Embed

Traditionalists fighting their rearguard skirmishes against the slobification of America suffered another defeat recently when the U.S. Senate abandoned its expectation that men wear a jacket and tie when on the Senate floor.

The kerfuffle had me thinking of how proper clothes once worked wonders for even the most awkward of men. Consider Abraham Lincoln: no dandy, but a man who knew how to make a statement with his wardrobe. As he was getting ready to leave for D.C., a luminary of the new Republican Party, Alexander K. McClure, paid a call on him in Springfield. McClure was taken aback by Lincoln’s shabby clothes — “snuff-colored and slouchy pantaloons,” the loose fit of which contrasted awkwardly with the too-too-tight sleeves of his dress coat.

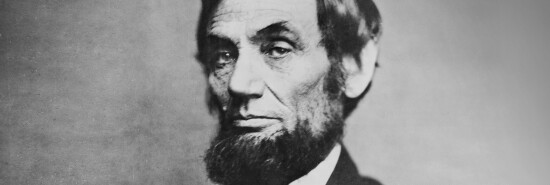

Slouchy as Lincoln may have been at home, he was savvy about what he wore in public. The stovepipe hat was a case in point. Lincoln might have tried to play down his gangly height but instead embraced the “topper” of his legal profession, wearing one that added another foot to his already towering frame. There was nothing foppish about Lincoln. He was formal in a black-and-white suited to an undertaker, a preacher, or a judge. It was a look that found an odd champion, one who recognized that fashion isn’t the same as style. Lincoln’s hat became an object of veneration — in some unexpected corners, I might add.

Some 60 years after Lincoln’s assassination, a group of artsy young Americans took up residence in Paris, among them Ernest Hemingway, Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, and the now rather less well-known society couple Gerald and Sara Murphy. The Murphys in particular became pals with Picasso. One day, the painter invited them to his apartment for drinks, Gerald told Calvin Tomkins. Once there, he gave Gerald and Sara a tour, showing them room after room crowded with half-finished paintings. But then Picasso, in the midst of all these works, “led Gerald rather ceremoniously to an alcove that contained a tall cardboard box.” Murphy recalled, “It was full of illustrations, photographs, engraving, and reproductions clipped from newspapers.” Every one of the images was of the same person — Abraham Lincoln. “I’ve been collecting them since I was a child,” Picasso told Gerald. “I have thousands, thousands!”

From the box, Picasso pulled out one of the portraits of Lincoln in an inky cloak taken by photographer Mathew Brady. Murphy remembered “the great feeling” with which the artist declared, “Voila la vraie elegance americaine!”

Now what passes for American elegance is the sort of get-up sported by Sen. John Fetterman (D-PA).

I could shake my head at it all but choose instead to reach for a cocktail shaker and let it do my tut-tutting for me. Gerald Murphy was a prolific author of original cocktail recipes, drinks that he served to his boozy pals, among whom were the Fitzgeralds. The Murphy drinks we know of are variations of a theme, the theme being citrus juices and mint-steeped gin.

Or perhaps, as this is the last of the Downtime columns I will be writing in these pages, I will end on an abstemious note. Abraham Lincoln was not a drinking man, but that doesn’t mean he isn’t worthy of that highest of civilian honors — having a cocktail named for you. Long ago, a simple mocktail was mixed up with Lincoln in mind. It was called the Rail Splitter. Here’s how to make one: Combine the juice of half a lemon with a half-ounce of simple syrup in a highball glass. Add ice, and fill the glass with ginger ale. Stir and enjoy.

Even better, put on a jacket and tie first, and add an ounce or two of bourbon to the drink. Raise your glass and toast the memory of true American elegance.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Eric Felten is the James Beard Award-winning author of How’s Your Drink?