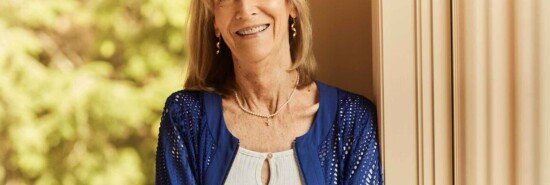

Sarah Young, 1946-2023

Graham Hillard

As a Christian missionary in Japan and Australia beginning in the late 1970s, Sarah Young kept a prayer journal. Writing down the daily focus of a prayerful mind is common, but what became of Young’s journal wasn’t common at all: It was eventually published and by the fall of 2013 had begun outselling Fifty Shades of Grey. Written in the voice of Jesus, Young produced a gently heretical Christian phenomenon. Young’s unlikely journey ended last week when she died at 77 from leukemia in Tennessee.

Tennessee is also where that journey began. Born there in 1946 as Sarah Jane Kelly, Young grew up in various Southern states before heading north to Wellesley College in Massachusetts. A self-described “non-Christian searching for truth,” the future author studied philosophy, graduating one year before more famous alumna Hillary Rodham. Though future schooling would take Young to Tufts, Georgia State, and Covenant Theological Seminary, Wellesley would prove foundational. Happening upon Escape from Reason, a 1968 tome by Christian apologist Francis Schaeffer, the recent grad found that her training had stood her in good stead. As Young would later tell the Christian Broadcasting Network, her philosophy classes “helped [her] to understand [Schaeffer’s] reasoning.”

She married Stephen Young, a fellow seminarian, in 1977 and soon began an embryonic version of what would become an evangelical megahit. In 2004, Young’s first book, Jesus Calling, was brought out by Nashville, Tennessee-based Integrity Publishers, soon to be bought by Christian book giant Thomas Nelson. By the end of 2008, the devotional text had sold an impressive 279,000 copies. By 2013, that number was 9 million.

The premise of Jesus Calling is simple enough. In short, calendar-based ruminations, the author speaks directly to the reader in the “voice” of an undemanding Jesus. As such, the pronouns “I,” “me,” and “my” refer to Christ himself (“I challenge you to relinquish the fantasy of an uncluttered world”), while “you” refers unfailingly to the reader (“You are trying to think your way through [your] trials”). If, as Richard Dawkins glibly put it, “the God of the Old Testament is … the most unpleasant character” in all of literature, Young’s Jesus is a life coach, cheerleader, and pop psychologist rolled into one. “I knew that God communicated with me through the Bible,” Young writes in the book’s introduction, “but I yearned for more.” That “more” is often not only extra– but un-biblical: juvenile, self-involved, tedious, and breathtakingly presumptuous.

Jesus Calling came in for no small amount of criticism in the years following its appearance. Traditionalist readers denounced the book as blasphemous, while conservative theologians warned that Young’s ideas ran counter to scripture in many instances. Perhaps the most damning response to Young’s work came from former occultist Warren B. Smith, whose book “Another Jesus” Calling (2013) accused the author of producing a “false Christ.” Yet nothing seemed able to slow Young’s momentum. By August of this year, Jesus Calling and its spinoffs had produced sales in the tens of millions.

Like Chicken Soup for the Soul, a brand with which it has much in common, Jesus Calling eventually launched sequels, swag, a podcast, a magazine, and a television show. A longtime sufferer of Lyme disease and other chronic conditions, Young remained a reclusive figure throughout, settling in Nashville but granting interviews only rarely. She leaves behind her husband, two children, six grandchildren, and three siblings.

Did Young do Christianity more good than harm despite Jesus Calling’s serious flaws? Without question, her books and products have inspired millions to think about Christ, however imperfectly. And she was, by all accounts, a lovely woman, serving the church abroad and others at home to the best of her ability. Nevertheless, it isn’t hard to see in the Jesus Calling phenomenon the same grim forces that have bound evangelicals to Donald Trump: laziness, anti-intellectualism, and a desire constantly to be flattered. (Full disclosure: I am an evangelical and voted for Trump.) If Young’s error was syncretism, the amalgamation of Christianity with other worldlier ideas, it was an error of which many others besides her are guilty.

Graham Hillard is a Washington Examiner magazine contributing writer and editor at the James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal.