HBO’s fascinating look at the other side of the telemarketer’s line

J. Oliver Conroy

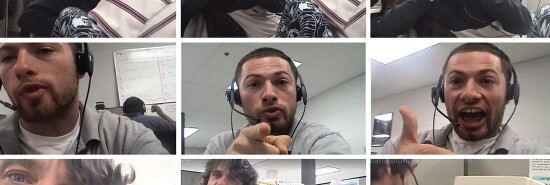

HBO’s new docuseries Telemarketers is a riveting, charmingly gonzo investigation of the industry by former telemarketers who first began documenting their job with camcorders two decades ago at a New Jersey phone bank later shut down by the Federal Trade Commission. Directed by Adam Bhala Lough and Sam Lipman-Stern and produced by Josh and Benny Safdie and Danny McBride, among others, the documentary is a scruffy sensation recalling the best early work of Michael Moore.

It’s not hard to see why the Safdie brothers, whose adrenaline-spiking crime features Good Time and Uncut Gems are peopled by indelible outer-borough fast-talkers, would love this material. Similarly, it makes a certain sense to learn that Lough was an executive producer of TFW NO GF, Alex Lee Moyer’s fascinating and controversial documentary about incels.

LABOR DAYS: BIDEN FACES GOP PRESSURE TO ORDER FEDERAL WORKERS BACK TO THE OFFICE

Telemarketers, a three-part series, flips back and forth in time. We open in 2001, when Lipman-Stern, a teenage high-school dropout, starts working as a caller at the banal-sounding Civic Development Group, or CDG. He’s working there for the simple reason that CDG is the only employer that will take him, and he soon realizes this is the norm. His colleagues are mostly dropouts, ex-cons, and recovering, or current, addicts, paid $10 an hour (no commission) to wheedle donations for altruistic-sounding causes. The office is raucous. Wild pranks, drug use, bathroom liaisons, and casual prostitution barely raise eyebrows. In some ways, it’s a fun place: a “big-a** cookout,” a CDG alum says.

The telemarketers’ biggest clients are police unions, as well as ostensible charities for firefighters, disabled veterans, cancer patients, and something called the “Children’s Wish Foundation.” (If you live in the United States, you’ve almost certainly received calls like this.) The charities allow telemarketing firms to solicit on their behalf despite the fact that the firms keep close to 90% of the donation revenue. The callers themselves are usually all too aware of the irony: felons calling on behalf of the police, sometimes while committing felonies. They call CDG “Criminals Doing Good” and joke between themselves that the only requirement to work there is the ability to pronounce the word “benevolent.”

Our subjects turn out to be stand-in examples of how the industry operates its personnel and offices: hire desperate people with no leverage, hold them to aggressive hourly quotas, and look the other way as long as the money keeps coming in. The canniest telemarketing firms, we learn, open call centers in economically depressed areas and recruit directly from halfway houses. “Crackheads” make the best telemarketers, one person argues, because who could be better at persuading?

Reading from scripts formulated to get around various legal settlements, the telemarketers use tricks to make it seem as if they work for the charities themselves rather than third-party solicitors: speak in an officer’s gruff bass, make vague references to “the guys” at the police lodge or firehouse, and relate sad stories about line-of-duty deaths. The best donors tend to be the elderly, conservative patriots angry about Black Lives Matter and the like, and frightened immigrants from impoverished and corrupt countries who believe they’re being extorted for police protection. The callers also offer to send donors pro-police decals to put on their cars, with the implication that the decals may help get out of a speeding ticket.

At CDG, Lipman-Stern meets Pat Pespas, a beloved industry veteran with a heroin problem who is renowned for his ability to pass out in the middle of a call and still close the sale. The jaded Pespas encourages Lipman-Stern, who has been making home videos at work for his own amusement, to think about documenting their industry in a more serious way. Later, Lipman-Stern recruits Pespas to assist in the reporting. Pespas, who, in addition to his addiction problems, is caring for his disabled wife and has never been on a plane, nevertheless enthusiastically agrees.

The essential shadiness of the business model is an open secret, and Lipman-Stern and Pespas use talking heads and investigative research to fill in the gaps. They talk to charity monitors, track down ex-colleagues, and get a Florida telemarketing entrepreneur, face blurred and voice concealed, to give gory details.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

The intrepid duo learns the owners of CDG, while paying their callers barely above minimum wage, owned Picassos and Van Goghs, that telemarketing pioneered working from home long before COVID-19, and that one of the best telemarketers in America is a convicted murderer. In the film’s most unsettling scene, we watch as he shakes down old ladies, his cajoling tone turning to chilling hatred the second they hang up. Along the way, Lipman-Stern and Pespas decide to expand their investigation: They’ve begun to question if the charities they assumed are victims in all of this are really victims at all.

Telemarketers isn’t perfect. As with a lot of docuseries, it’s padded out to justify its three-episode arc. Yet the result, despite or because of its essential amateurishness, has vitality and heart. It’s satisfying to watch former headset grunts turn their skills on their own industry. They’re endearing, dogged lumpenproles with nothing to lose, unapologetic about their pasts and personal flaws, and they’ve created a documentary as insightful and interesting as anything produced by the Ivy League-educated ranks of “real” journalism.

J. Oliver Conroy’s writing has been published in the Guardian, New York magazine, the Spectator, the New Criterion, and others.