Reviewed: The Syriac World: In Search of a Forgotten Christianity by Francoise Briquel Chatonnet and Muriel Debie

Sam Sweeney

A few years ago, I was in Paris and bought three books in French. Given my mediocre ability to read that language, it was overly ambitious. One of the books has remained unopened since, a second one started but unfinished. I had finished reading the third book, however, by the time I left Paris. It was well worth the struggle through the language of Voltaire, and it remains one of the best books I’ve ever read. Thankfully, that book, The Syriac World by Francoise Briquel Chatonnet and Muriel Debie, originally published in French in 2017, is now available in English translation.

Much attention has been given to the plight of the Middle East’s Christians in recent years. The Syriac World is the best place to start for those wondering about the history of those communities, whose continued existence is under threat. Most books in the field of Syriac studies require a dictionary and encyclopedia to get through for the lay reader, but The Syriac World is suitable even for a casual ride on the Parisian Metro. It’s a rare treat when scholars succeed in producing a book detailing their work for a broader audience and do so in a way that is accessible even to those without a background in their subject of study.

HOW TO WRITE A BIOGRAPHY WITHOUT BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION

While Syriac studies has a long tradition in the Western academy, it is rarely referenced in the broader culture. As the authors write, “next to Latin and Greek, Syriac is the third most important branch of ancient Christianity. As the heir to Greco-Latin antiquity, the Western world is largely unaware of this Christian tradition, which is anchored in Hellenism but also descended from a Near Eastern and Semitic past. In parallel with the Greco-Latin tradition in the West, it spread to the East in the first centuries of Christianity, eventually reaching as far as India and China.”

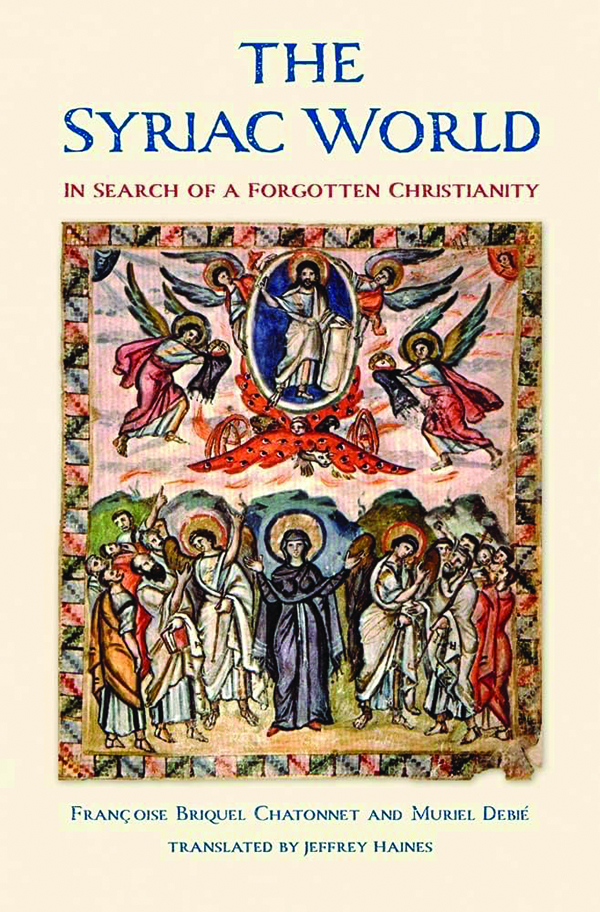

The English edition of The Syriac World is not quite as visually stunning as the French, but it is still well supplemented with maps and pictures. The reader takes a visual journey through some of the most important early Syriac inscriptions and mosaics. Later, the focus shifts to manuscripts, where much of Syriac literature remains hidden away. Jeffrey Haines’s translation is excellent and makes the book feel like it was written in English.

An overview of Syriac Christianity will hold significant interest for anyone interested in Christian history. “Apart from the Greek translation of the Old Testament known as the Septuagint,” the authors write, “Syriac offers the only ancient translation of the Old Testament made directly from Hebrew before the Masoretic texts (that is, before the fixation of the massorah or the canonical Hebrew reading established in the 8th century). This version, the Peshitta or ‘simple’ version, was most likely made by Jews or converted Jews in northern Mesopotamia around AD 150 and is of great interest for ancient Jewish and Christian exegetical practices.”

Most surprising, even to readers well versed in Christian history, will be the extent to which Syriac Christianity spread eastward. As the authors write: “The first phase of Christianity in China extends evenly before and after the Arab Conquest. The arrival of Christianity in the heart of the Chinese Empire, under the Tang dynasty, is documented by an exceptional piece of evidence, a stele [or engraved slab] discovered at Xi’an, at that time the capital of the Tang kingdom. It was uncovered in 1625, and its discovery had a tremendous effect on the European world by showing that Christianity had spread in China almost a thousand years before the arrival of Latin missionaries.”

The authors highlight one of the most interesting texts in Syriac, dating to the 13th century and worthy of a Hollywood adaptation: “One exceptional travel account in an inverse sense, from east to west, exists. It relates in Syriac the story of a voyage, written in the first person, of a Christian monk, Rabban Sauma, who left China in order to travel to Jerusalem with a companion, Rabban Marcos. He traveled across all of Asia, with the goal of going first to Baghdad to meet the East Syrian patriarch, Mar Denha … He completed several diplomatic missions for the patriarch … but had to give up on traveling to Jerusalem, as the journey was too dangerous.” His travels eventually took the Chinese monk to Constantinople and further, all the way to Naples, “where he met the king Irid Sharlado (the Syriac rendition of King Charles II, le roi Charles deux in French). He then went to Rome, where the pontifical seat was temporarily vacant, and explained his faith to the cardinals there.”

Briquel Chatonnet and Debie are recognized Syriac scholars who have published important works for specialists in their field. They were still able to convey their extensive knowledge and expertise accessibly. Readers of English are fortunate that this book has finally been translated for them to enjoy as well. It is not going too far to say that the triumph of The Syriac World, which walks the tightrope between substance and style so gamely, should serve as a model for books on more obscure academic topics outside of Syriac studies.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Sam Sweeney is the president of the Mesopotamia Relief Foundation.