George Washington Carver for adults

Haisten Willis

One of the most widely taught figures in America’s classrooms, especially during Black History Month, is George Washington Carver, the famous inventor of more than 300 uses for peanuts who toiled away at Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute.

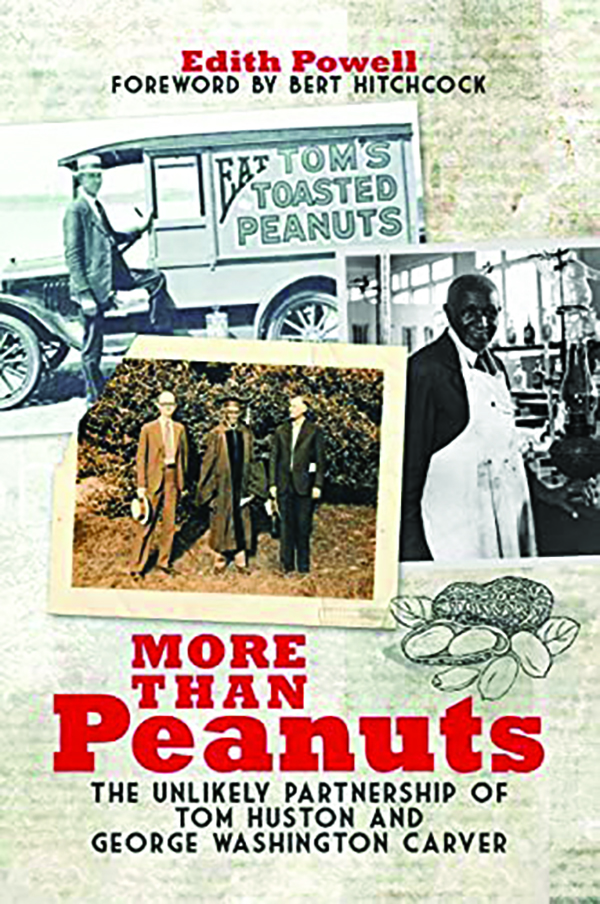

Carver remains a household name some 80 years after his death, but a fascinating and little-known aspect of his story is detailed in Edith Powell’s new book, More Than Peanuts: The Unlikely Partnership of Tom Huston and George Washington Carver.

Huston, like Carver, was a prolific inventor who greatly boosted the fledgling peanut industry 100 years ago, creating not only a peanut sheller but a roasting process and packaging, inventing every element needed to produce the little packs of salted peanuts you can find at any gas station today.

Unlike Carver, Huston was restless and unsettled, building a multimillion-dollar peanut empire in 1925 and losing it just seven years later after he bet the house on a too-far-ahead-of-its-time frozen peach venture. Also unlike Carver, Huston was white.

One might think that presented a major barrier to partnering with Carver in the segregated South of the early 20th century. Yet, as is detailed in the book, this wasn’t the case. The two first made contact in 1924 and remained in touch via frequent visits and hundreds of letters, a partnership that ended only at Carver’s death in 1943.

Carver and Huston’s intensely aligned interests far outstripped any social concerns over class or skin color.

Peanuts, which have long since become shorthand for any impossibly cheap and abundant commodity, scarcely registered as a cash crop a century ago, typically fed to hogs if they were grown at all.

Instead, the South was crippled by its near total reliance on cotton, which drained the soil, suffered from overproduction due to the lack of any viable alternative, and in the early 1900s, was devastated by the boll weevil as a final insult.

Enter Carver and Huston, a pair of Southern superheroes. Huston, a farm boy who hated shelling peanuts by hand, first invented machines to do it for him. When the machines proved too durable and thus unlikely to make him rich, he created the roasting process and plastic packaging.

The public went, um, nuts. Huston’s company soon sold more than a million packages of “Tom’s Toasted Peanuts” a week, earning him two appearances in Time magazine.

Carver, in turn, desperately sought to help black farmers escape from cotton, which led to his own furious promotion of peanuts.

Huston first reached out to Carver for roasting advice, seeking to put the flavor “inside the peanut” rather than outside, where it leaked all over the consumer’s hands.

This one letter soon led to dozens in which the pair, later joined by two of Huston’s employees, discussed all manner of peanut problems, ranging from roasting to packaging to plant diseases.

Huston’s company, Tom’s, was located in Columbus, Georgia, just 45 miles from Tuskegee in the heart of what was later dubbed the peanut belt, and grew into a regional snacking empire that put food on the table for thousands of farmers and company employees alike. It went bankrupt in 2005, but one can still find Tom’s-branded chips and pork rinds at most any southeastern convenience store.

In full disclosure: I was born in Columbus, and my father, both of my grandfathers, and all of my uncles worked for Tom’s at one time or another. Carver and Huston’s economic impact cannot be overstated.

Powell, a retired Tuskegee professor, presents many of the men’s letters in full and mercifully refrains from showcasing their partnership through the lens of 2022 politics.

The epistolary nature of the book means we see the relationship as it develops. The letters are written in the present tense, which was so favored by the great novelist John Updike for its “flickering quality,” happening right now, in front of you.

Of course, the prose does not soar to great heights here, but then, it isn’t supposed to. These guys are about business. As such, it’s interesting to note that neither profited directly from the partnership. Carver sought to help “my people,” meaning black farmers, and wouldn’t take payment, while Huston bought peanuts but did not grow them.

They each saw the larger picture of their work, first in cooking and preserving the product and then, for most of the book’s length, battling diseases that threatened the new cash crop.

It paid off, and peanuts are still grown by the trillions in Georgia and Alabama today. In another unlikely partnership, Sens. Raphael Warnock (D-GA) and Tommy Tuberville (R-AL) teamed up last year to push pro-peanut measures at the USDA.

Washington plays a surprisingly important role in the history covered by the book as well. Carver and company knew they needed to get the USDA interested in order to secure research dollars to fulfill their mission, yet they were distrustful of the government. Bob Barry, one of Huston’s employees, wrote to Carver that “people in political jobs are not looking for hard work as a rule” — a bipartisan statement if ever there was one. In the end, they succeeded in getting the federal government involved, so much so that it greatly reduced the frequency and urgency of contact between Carver and Huston.

Nonetheless, this series of events was no small part of Carver’s story. “The Tom Huston Peanut Company’s plan interests me more than anything that I have come in contact with,” Carver writes in one letter. That respect goes both ways, with Huston telling Carver, “You certainly deserve a place on America’s front page,” and Barry adding, “I will always consider you one of my very best friends.”

Since Carver wouldn’t take payment for any of his work with Tom’s, Huston offered him a job at the company in 1929, which the scientist also refused. To show his appreciation, Huston then commissioned a bronze bas-relief plaque of Carver, which was presented to him at a Tuskegee graduation ceremony.

Tuskegee President Robert Moton, who spoke at the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial and whose name graces the field where the Tuskegee Airmen practiced, was present and said simply that the plaque was deeper than it appeared on the surface. One of Huston’s employees, so moved by the occasion, confessed his family’s former ties to the Confederacy in a subsequent letter, writing, “To your people this should prove that the man within is greater than his skin. Many of my race also have that lesson to learn.”

Apart from these special occasions, the topic of race is notable largely for its absence. Huston and Carver focused on achieving their peanut dreams and saw how they could help each other.

While that leaves some of the reading a little down in the weeds, with details about this or that nut disease and what might be done about it, the lesson remains all the same.

Haisten Willis is a White House reporter for the Washington Examiner.