Black Mirror is back with a sixth season to make us wonder if we are building a horror future

Michael M. Rosen

“I feel like I’m not the main character in my own life story,” Joan, a character played by Annie Murphy in one of the episodes in the new season of Netflix’s Black Mirror, tells her therapist at the beginning of the episode.

Indeed, this unsettling sense of dispossession — of a lack of ownership over our bodies, minds, and narratives, of subjugation to the technological control of more powerful forces — this is the stuff of which the hit dystopian show is made. And its sixth season hammers this point home as well as any since the show’s origin.

Showrunner Charlie Brooker himself has aptly described the new season as a “reset.” And it is. The most recent season aired four years ago. The new set of five carefully cultivated episodes represents the first post-pandemic installment after previous seasons meandered from the show’s core strength, i.e., holding up a mirror to contemporary society’s overuse and misuse of the peculiar forces unleashed by today’s technology.

THE POLITICIAN SUFFOCATES THE ARTIST IN BOOTS RILEY’S NEW SHOW I’M A VIRGO

Some variations on the show’s theme reflect deft artistic judgment. For the first time in the show’s short history (apart from a 2018 Black Mirror-themed choose-your-own-adventure experience named Bandersnatch, which was set in 1980s Britain), we travel back in time in certain episodes to experience what technology was, or could have been, in the past. Brooker treats us to a story about 1969 astronauts deployed in deep space on a multiyear mission, to 1980s home videos (“The tab’s punched out. It stops people recording over it”), and to the fashions and machinery of 1979 on the eve of Margaret Thatcher’s election.

Other new episodes, like some Black Mirror classics, introduce viewers to technology that, while not quite operative yet, seems to be just around the corner, such as quantum computers, artificial intelligence-powered instant and (incredibly lifelike) deepfakes, and the transplantation of consciousness into robots. But more than anything, a single major disturbing and thought-provoking theme runs through all five episodes: how we act when we know others are scrutinizing us, whether and how we should regard those we scrutinize, and how we react when the scrutinizers abruptly become the scrutinized.

For instance, in “Loch Henry,” Davis, the protagonist, sets out to record a documentary about a grisly decades-old murder-suicide in a pastoral Scottish hamlet that aims to excavate the milieu and motivations of the killer and his victims. Combining modern film techniques with the videotape technology of the 1980s, Davis digs deep in basements and trawls archival footage and newspaper clippings. But his efforts rile some of the locals, who wish he’d let the dead sleep in peace. And when the inevitable plot twist hits — very hard — the tables turn, and Davis finds himself a passive, haunted subject of the documentary.

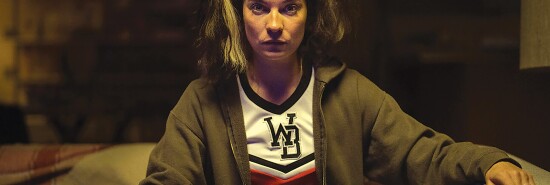

Similarly, in “Joan is Awful,” Annie Murphy’s character plops down on the sofa one night after a dreadful day of work to watch a new streaming series starring … herself. A stunningly accurate depiction of her day ensues, prompting disbelief and triggering an unlikely adventure with Salma Hayek (playing herself) that covers the sublime, the mundane, and everything in between.

Likewise, “Mazey Day” features a troubled movie star who visits an unusual rehab center outside of Los Angeles under the watchful panopticon of unethical paparazzi. When Bo, a broke but sympathetic paparazzo played by Zazie Beetz, has second thoughts about the oppressive lens she and her colleagues have trained on Mazey, they’re vanquished by curiosity. “F***ing privacy screens,” a fellow pap exclaims outside the rehab compound, “which means whatever they do on the other side has gotta be worth seeing.” Like Bo, the viewer can’t help but follow as they tunnel under the wall.

In “Demon 79,” a retail sales clerk, inadvertently possessed by an emissary of Mephistopheles, is obliged to perform a most distasteful mission in which, with the emissary’s assistance, she regards the miserable futures of her victims as a prelude to doing them grievous harm. Eventually fed up with her duties, the clerk shouts at the smirking demon, “No blood on your hands. You’re just watching!”

Finally, in “Beyond the Sea,” Aaron Paul’s exquisitely restrained astronaut, Cliff, “travels” from his spacecraft to Earth, where his consciousness inhabits a robotic avatar and observes his actual family’s life. When tragedy befalls his copilot’s family, the earthbound miscreant exults that “the machine man will watch with his heart screaming a million miles above us.” The remainder of the episode involves a profound reflection on the power of observation — how we experience life, how we process it, and how we recreate it.

In all cases, Brooker confronts viewers with wrenching, even brutal, evidence of our indecency, our scabrous voyeurism, our naked complicity in a technologically turbocharged near future that we simply cannot resist.

Indeed, in perhaps the best example of the recursive, ouroboric nature of reality, the show mercilessly lampoons its own platform, Netflix, as the origin of key technological trends. In two episodes, the executives of a stand-in streaming network, thinly veiled under a fake name, come in for a lashing for promoting “engagement” at the expense of good judgment. “When we focused on their more weak or selfish or craven moments,” the CEO reports in “Joan is Awful,” “it confirmed their innermost fears and put them in a state of mesmerized horror … which really drives engagement. They literally can’t look away!”

As we, the viewers, watch the CEO utter these distressing thoughts about the fictional audience whom we are watching, that familiar thought appears, as it has since Black Mirror’s first season: “In this horror, we are watching ourselves.”

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Michael M. Rosen is an attorney and writer in Israel and a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.