Reviewing the history of action movies

Peter Tonguette

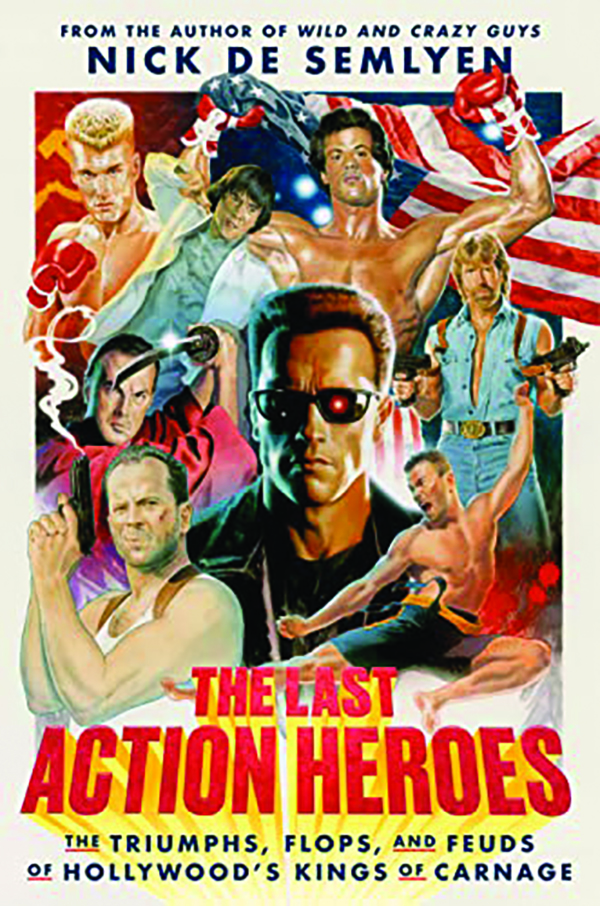

Like shopping malls, instant messaging, and power suits, the action movie genre once looked like it would last forever. Throughout the 1980s and into the ’90s, a group of muscled male movie stars, Sylvester Stallone, Bruce Willis, and Arnold Schwarzenegger foremost among them, rendered the genre among the foremost American exports. As the Western was in the 1940s and ’50s, the action movie was the vessel through which the wider world understood the United States in the last quarter of the 20th century. Movies including First Blood, Die Hard, and Terminator 2: Judgment Day communicated in the international language of brawn.

I still remember the feeling of satisfaction I felt when I saw the third Die Hard movie, 1995’s Die Hard with a Vengeance. Aided by the punchy, vigorous style of director John McTiernan, this was a movie that fulfilled expectations. Nourished by a steady diet of similar action epics, I was prepared for every character type I encountered during the two-hour-plus running time: Willis’s scruffy, weary, impolitic police detective John McClane, Samuel L. Jackson’s sharply sardonic sidekick Zeus, Jeremy Irons’s riddle-addicted psychopath Simon, and so on.

CAN JENNIFER LAWRENCE RESURRECT THE SEX COMEDY?

Yet unbeknownst to ticket-buyers at the time, Die Hard with a Vengeance was among the last of its kind. The action movie genre it so robustly represented would soon be headed the way of the dodo. Audiences were increasingly immersed in fantastical comic book adaptations and science-fiction fare. The He-Men whose strapping likenesses gave the genre its primacy, including Sly, Bruce, and Ahnuld, began, bit by bit, to lose their luster. Like many things in life, though, we didn’t know their era had passed until it was already over.

In an entertaining new book, author and Empire magazine editor Nick de Semlyen gleefully recounts the rise of the action movie genre and mournfully tells of its inevitable decline. It turns out that even Die Hard with a Vengeance was itself embarked on with some reluctance by its participants. As early as 1992, three years before the release of the movie, Willis said he was looking to move on from the genre. “I’m getting sick of carrying guns in movies,” said Willis, who nonetheless set aside his qualms for a salary reported to be $13 million (and who years later, with his career in a state of serious decline, agreed to participate in two additional sequels).

But we can save the eulogies for later. Much of the book is unapologetically, if sometimes ironically, appreciative of the manly, martial virtues the genre promoted. “For all their limitations, those movies rarely failed to take huge swings, to destroy creatively,” de Semlyen writes. “They are, in a way, the spiritual successors to the Greek myths of yore, tales of derring-do to stir the spirit and excite the soul.”

De Semlyen’s reference to the Greek myths is apropos. The stars who defined the genre in the ’80s and ’90s differed from their forebears in resembling gods more than mere mortals (or actors). Clint Eastwood, Steve McQueen, and Burt Reynolds could each wield guns or take command of cars, but they were human-sized heroes. By contrast, the stars of the Reagan era were first and foremost defined by their immovable physical force. Stallone was dubbed “the Italian Stallion,” Schwarzenegger, “the Austrian Oak.” “Each of these stars had a distinct way of plying their deadly art,” de Semlyen writes.

Fittingly, many of them were first trained in one of the deadly arts rather than the (ahem) performing arts. As most of us know, Schwarzenegger’s title of Mr. Universe preceded his role as the Terminator, and Jean-Claude Van Damme was semi-famous as Mr. Belgium before he became semi-famous for his on-screen splits. Chuck Norris was first known as a karate champ, and Steven Seagal had something or other to do with aikido. These are real achievements, but let us not forget that each of these men sought stardom before trophies. Even Schwarzenegger, who demonstrated his gifts as a serious actor in an early part in Bob Rafelson’s Stay Hungry, admitted to an acting coach: “I love what you do. But that’s not the direction I want to go. I want to be an action-adventure actor.” And as an adolescent near Brussels, Van Damme seems to have been moved by a viewing of Star Wars, the plot of which he described this way: “The guy in the small village working in mechanics and then they give him the power to be a ninja of the future.”

Van Damme, like Seagal and Dolph Lundgren, two of the book’s other main subjects, certainly embodies the dorkiness typical of many ’80s-era action movies. Yet de Semlyen must be credited for taking the genre’s best films semi-seriously. We are reminded that Stallone’s first Rambo movie, First Blood, came on the heels of a wave of glum films depicting the consequences of Vietnam veterans making their way homeward. “This movie fused a similar message — respect our vets — with bombastic action thrills,” writes de Semlyen, who describes the ensuing Rambo franchise as having a cleansing effect on a public tired of being told to think badly of their country: “First Blood Part II was a new kind of Vietnam picture, one in which military power was celebrated, not apologized for.”

Meanwhile, Norris’s movies are described as being almost obsessively preoccupied with American soldiers who had gone missing in action in Vietnam. Even his silliest epic, Invasion U.S.A., about the attempted takeover of the nation by Latin American terrorists, is said to have inspired freedom-loving moviegoers in Communist Romania. “They use the poster, to this day, in Romania when they protest against the government,” screenwriter James Bruner said.

Only the most pompous and pleasure-denying moviegoer, though, can resist the kinetic toughness and emotional directness of Bloodsport, Rocky II, or Conan the Barbarian, whose director, John Milius, properly understood its dimensions. “Conan is a barbarian, and I related to that instantly,” he said. “I love Genghis Khan, I love the Vikings, I love the Apaches and all primitive warrior cultures.”

That appetite for action remains even in our technological age, so what killed our action heroes? The 1989 Batman looms large — “The action movies changed radically when it comes possible to Velcro your muscles on,” Stallone said — as does Steven Spielberg’s 1993 blockbuster Jurassic Park. In part, it was the very impatience Willis expressed with “carrying guns in movies.” Schwarzenegger and Stallone both maneuvered their way into comedies — the former successfully with Twins, the latter most ill-advisedly with Stop! Or My Mom Will Shoot. Unsurprisingly, Seagal, Van Damme, and Lundgren were never cut out to be long-term big-league movie stars. Norris was content to dawdle on TV in Walker, Texas Ranger. Jackie Chan, whose Rumble in the Bronx was a surprise blockbuster in the genre’s twilight, now says he has more artistic freedom when working in Asia.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

The book derives its title from the notorious Schwarzenegger bomb Last Action Hero, the making of which reveals a curious and telling lack of confidence in the genre on the part of its makers. “The head of the studio couldn’t decide whether this was an action movie or a kids’ movie,” director McTiernan said.

Perhaps all great art forms have short half-lives. Undeterred, de Semlyen evokes this one with aplomb. This is a book that makes you ache for the days when the movie screen belonged not to men who dress in superhero capes but to those who lift weights.

Peter Tonguette is a contributing writer to the Washington Examiner magazine.