The politician suffocates the artist in Boots Riley’s new show I’m a Virgo

Armin Rosen

The rapper-turned-director Boots Riley has discovered a variation on Chekhov’s gun so stunningly original that he deserves to have all genital corollaries to the rules of narrative inevitability named after him. If a group of drunk women outside a nightclub beckon a 13-foot tall 19-year-old black man to “show us that dick” in Episode 1 of a high-concept television comedy, you can bet you’ll be seeing a depiction of the member in question somewhere near the season’s climax. Episode 4 of I’m a Virgo, Riley’s new series on Amazon Prime, is artfully titled “Balance Beam,” and during a poignant and surreally mismatched sexual encounter, our hero’s vast appendage, a dark comic stand-in for a uniquely American history of fetishism, jealousy, and fear, is suggested through a series of steamy close-ups on the giant’s legs and forearms.

Boots is a hard-line revolutionary communist from Oakland, and thus I do not think he intended his viewers to recall the Bible’s repeated use of “feet” as a synecdoche for regions further north. I don’t know that a lot of the associations raised by Riley’s overstuffed and overstimulating experiment were strictly intentional. The hydraulic skyscraper containing the home and corporate offices of The Hero, a San Francisco tech billionaire superhero who publishes comic books about his exploits, is a likely reference to downtown Neo Tokyo in the foundational anime series Neon Genesis Evangelion. “All art is propaganda,” broods The Hero, played by the chameleonic Walton Goggins. “My whole life is propaganda — righteous propaganda!” This is less clear of a callout since the possible reference isn’t to an icon of nerd culture or black culture but to Riley himself: The filmmaker has a similar view of art and his role in the world as his creation does, but he puts these words in the mouth of a psychopathic arch-capitalist white man whose name is an unctuous celebration of his own virtue. Could The Hero be a deliberate mirror image of Riley, a warning to viewers not to trust any political ideology that’s being fed to you under the guise of pop culture? And is Riley, one of the last public cheerleaders for the “revolution” in Venezuela and someone of overall lunatic political judgment, really capable of that level of self-awareness?

OUR PLANET II IS GREAT ANTI-HUMAN ART

The surprising answer, at least for those familiar with Riley’s exhausting 2018 film Sorry to Bother You and his much more brilliant but still politically overheated rap career, is “Yes, he is.”

I’m a Virgo asks what a genuinely anti-capitalist superhero story would actually look like in a polarized and declining America, and Riley generally follows the experiment where it takes him, paying thrillingly scattered attention to narrative cohesion, mainstream cultural pieties, or the strictures of his own doctrinaire worldview. Riley makes the most of an artistic freedom that only people at the fringes really have these days.

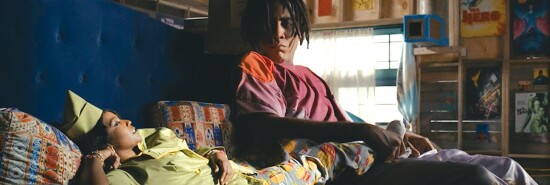

The show tells the story of Cootie, a giant whose family keeps him hidden in their middle-class Oakland bungalow, and the strange and talented downtrodden who gather around this ambitious naif, depicted by a permanently befuddled Jharrel Jerome (Moonlight), once he finally leaves home. There’s the love interest, a Flash-like speed demon who works at a burger stand, along with an entire city block of poor, mostly black folk who have mysteriously been shrunk to the size of street vermin. Jones, a rent strike organizer with the word “liberation” tattooed across her neck, has the greatest superpower of all: dialectical materialism. She inflames the workers’ rage and breaks their class enemies’ will with communist TED talks filmed in side-scrolling comic book style.

A lot happens in this show — too much, really. Oakland devolves into a familiar nightmare of strikes, riots, and blackouts as the American center fails to hold. A cult of white people dressed in Steve Jobs turtlenecks believes Cootie is the messiah, an eye-rollingly literal expression of the “magical negro” trope in pop culture. Much more successful satire comes through an Adult Swim-style animated show within a show called Parking Tickets, filmed at a cinematic level of quality and narrated at one point by Slavoj Zizek. The interludes are a nihilist counterpart to Jones’s stirring speeches, feats of hypnotic mass-market narrative that instead cause a crippling fatalism, powerlessness, and languor. A DVD of the series’s lost episode, so despairing that it induced a total loss of motor control in 93.5% of viewers the one and only time it aired, is deployed as a weapon once Cootie decides to take the fight against overpolicing, inequality, and exploitation of the poor into his own massive hands.

For its first few episodes, I’m a Virgo seems as if it will be Riley’s spin on an idea that’s endured on the more existential end of African American art and literature, which is that the fundamentally vilified and alienated young black man becomes a monster not just to terrified whites or to suspicious members of his own racial grouping but to himself as well. It would have been a cheeky, even provocative inversion to update Invisible Man through a story about a 13-foot behemoth from the ‘hood. But as the series progresses, and as The Hero emerges as Cootie’s main antagonist, it’s clear Riley has something else in mind. The Hero represents the supposedly racist myth of the virtue of law and order promulgated by the superhero-industrial complex, which has now devoured much of American pop culture. The Hero is an unstable and nearly suicidal mama’s boy, meaning I’m a Virgo is also skewering the complex’s tendency toward darkening its main characters as a shortcut to social responsibility and narrative depth. From a communist perspective, there is no insight or redemption to be had in the Marvel Cinematic Universe or even through the fake subversiveness of Adult Swim-type hyperirony. The machine isn’t built to produce anything interesting or true, Riley alleges.

He’s correct, of course. Communists might be farcically wrong about economics, history, foreign policy, and a host of other nontrivial issues, but at least they exist far enough outside the gray rainbow world of centrist respectability to be able to point out how dull and deadening it all is. Pointing is about the best they can do, though. Communists think the culture has decayed because they see everything they dislike as the oppressive extension of the capitalist system of production when the real answers lie in an intangible realm whose very existence a strict materialist would deny.

This blind spot notwithstanding, Riley can show a remarkable ability to extend his critique to his own side: Cootie’s guerrilla tactics, and his team-up of subaltern superheroes, quickly meets the hard reality that radical direct action doesn’t work against governments or large corporations and that certain types of well-intentioned activism can actually make things worse. What does work, according to Jones, the supernaturally effective orator, is starving the system from below through general strikes and communes. But Jones launches such a strike by crassly exploiting popular anger at the death of a friend who bled out at the entrance to a hospital where he was denied treatment — a friend who, we’re told more than once, didn’t really care about politics.

As in the inferior Sorry to Bother You, propaganda eventually wins out over art, even if it takes us a lot longer to get there in I’m a Virgo. In both cases, Riley’s focus gradually shifts away from a tangle of ever-more nonsensical storylines and toward his need to sell his political program. Riley is the one and only communist in America who has gotten Jeff Bezos to fund and broadcast a four-hour-long case for anti-corporate revolution, and he grows increasingly anxious about wasting the opportunity. Disaster finally strikes in the closing minutes of the series’s seventh and final episode, when the season’s drama wraps up through a devastating and ludicrous lecture filmed like a superhero battle about how crime only exists because capitalists create unemployment in order to goose the labor pool so that they can deprive workers of their bargaining power. This is a conspiracy theory brought dazzlingly to life — Riley isn’t just normal wrong but heroically wrong, the rare artist who embraces the risk of embarrassment inherent in answering to no one.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Armin Rosen is a New York-based reporter at large for Tablet.