A better look at James Garfield

Carl Paulus

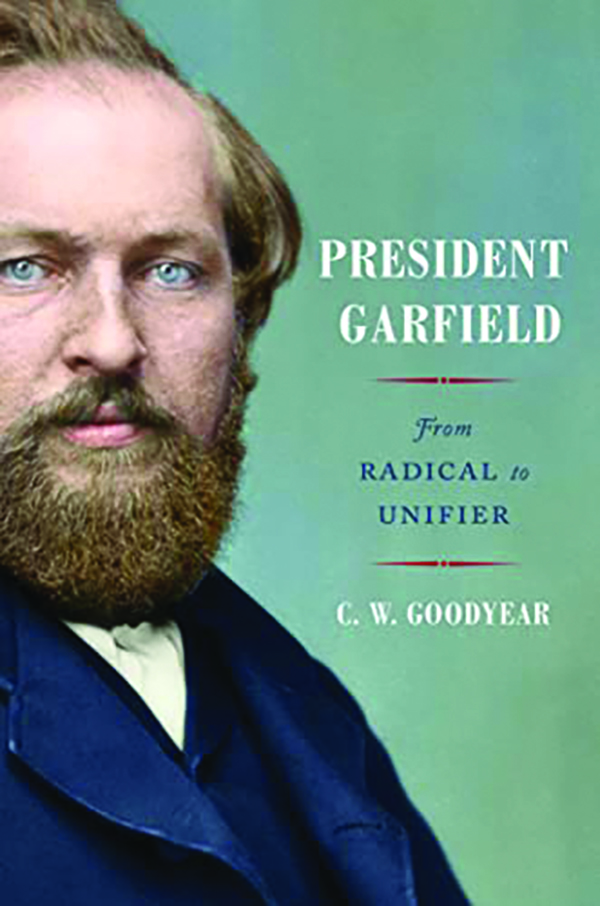

C.W. Goodyear’s excellent new biography President Garfield: From Radical to Unifier, offers an extensive study of an academic, general, and statesman whose death has overshadowed his accomplishments and service to his country. Garfield’s long career at some of the highest levels of American policymaking serves as a reminder that the ability to negotiate while maintaining firmly-held principles might be a rare combination in politics, but not an impossible one.

The Washington Post once referred to Garfield as “the best president we never had,” a title I think belongs to William Henry Harrison. President Garfield reveals in clear detail the important difference between the terms of our two shortest-tenured presidents. In over 600 pages, Goodyear illustrates the life of a shrewd member of the House, the only one to ever go from the lower chamber to the White House, revealing how he played the game of politics and succeeded in what he believed were his most important tasks at hand. Although he did not live to see the results, as his life in the White House was cut tragically short by a lunatic in search of a job, the public did reap what he had sown and was better for it.

LIGHTHIZER’S TERRIBLE NEW BOOK

The author breaks Garfield’s life into four parts: his childhood in Ohio, the Civil War, Congress, and the presidency. He tells a real-life Horatio Alger story, similar to those that became bestsellers in Garfield’s era. (In fact, the popular writer penned the very first biography of the then-Republican presidential nominee in 1880.) Like Ragged Dick, Garfield grew up very poor with few prospects outside of his smarts and work ethic. Coming of age in what Goodyear calls “The Wilderness,” a fitting name for Ohio if there ever was one, the future president was born to a family well acquainted with tragedy. James was named after a deceased older brother and his father died when he was merely a toddler.

Goodyear meticulously tells the tale of Garfield’s rise from pulling mules on canal boats to holding the most prestigious post in the United States, charting his path to becoming “a radical” opposed to the institution of slavery who later “unified” a splintering party. He also details ways that the future president supported black Americans coming into the political and social fold with equal footing, something well recognized at the time of his death. Goodyear’s epilogue elegantly details the creation of the touching monument to the slain president built by the buffalo soldiers in Arizona, which still stands today — a fitting tribute to his success implementing “radical” policies.

Garfield felt the pressures of the time he lived in and wanted to shape the world around him. Unlike some radical trends today, however, the future president also held a firm commitment to the institutions he served, even when doing so created obstacles to the social changes he wished to see — in his case the eradication of slavery. Like many American leaders, Garfield did not want to topple and replace democratic institutions, he wanted them both preserved and expanded. He aimed for democratic inclusion.

While juggling such ideals and impulses might be easier in Congress, where anti-institutional urges are purposely curbed, Garfield showed a fervent commitment to institution-building in all of the offices he held, something that should be aspired to today. For example, throughout his tenure as principal of the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute, now Hiram College, Garfield developed a growing disdain for slavery. Yet as the school’s leader, he sought to maintain institutional neutrality on the matter, knowing that doing otherwise could undermine the credibility of the college he’d been tasked to protect. Throughout President Garfield, Goodyear reveals a leader willing to maintain the primary missions of the institutions he served while doing the hard work within those constraints of trying to rectify injustices or squelch corruption to build something better in the long run.

Over the next two parts of the book, Goodyear reveals considerable skill as a writer, profiling Garfield’s rise both as a local politician and a soldier before detailing his leadership on the battlefield and in the House of Representatives during the Civil War and Reconstruction. Half war story, half House of Cards, readers are taken to Kentucky and Tennessee as Garfield maneuvers the politics of the Union Army and survives treacherous battles, including Chickamauga, where he became a hero at the expense of the reputation of the general he served as chief of staff.

One minor critique I have of Goodyear is the title of the book. Garfield, as the book deftly portrays, did not make a change from “radical” to “unifier.” Rather, Goodyear offers instance after instance of the 20th president being a radical and a unifier simultaneously, dealing in negotiations while also being willing to walk away. For example, when he walks out of the infamous meeting at Wormley’s Hotel when the Compromise of 1877 was hammered out by Republicans and Southern Democrats to make Rutherford B. Hayes president. Garfield walked the tightrope of idealism and reality well.

In many ways, and due to Garfield’s short tenure in the White House, President Garfield is more valuable as a history of Congress during the period than a presidential biography. Throughout his time in the House, we see the importance of Garfield’s intellectual and ideological consistency. Goodyear writes, “Only Garfield seems to have navigated all the strife [of post-Civil War] politics without much issue; he had certainly witnessed more of it than almost anyone. His House tenure measures as almost a record-breaker, and from an increasingly powerful perch in that body he had participated in almost every major American political event since the Civil War: presidential administrations, constitutional amendments, economic catastrophes, an impeachment, election crisis, Klan violence, and more had come and gone. Garfield served as one of the republic’s few constants throughout it all.” Not everyone agreed with him, but his workhorse mentality stood out amid a sea of show horses and grifters that often made up the bulk of his peers.

A major strength of President Garfield comes in the way it navigates and explains the complexities of post-bellum politics. With the aplomb of a more seasoned writer, Goodyear reveals the personalities that dominated the political machinery of the factions of Republicans that rose to power during Reconstruction. We don’t just see the human side of Garfield but also of the other power players in Congress, namely, Schuyler Colfax, James Blaine, and, in many ways the villain of the story, Roscoe Conkling.

This is the only way an author can transform the banality of fights over civil service reform into a page turner. Throughout the last third of the book, including his chapters on Garfield receiving the Republican nomination, becoming president, and being assassinated, we see the difference between being a compromiser and being a moderate. Garfield wanted civil service reform because he understood that the so-called spoils system threatened the democracy he and millions of others fought for during the Civil War. He didn’t shy away from his principles and the direction he wanted the country to go, but rather found ways to cut deals and gain victories, which eventually led to the presidency being foisted upon him in 1880.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Carl Paulus is a historian from Michigan and author of The Slaveholding Crisis: Fear of Insurrection and the Coming of the Civil War.