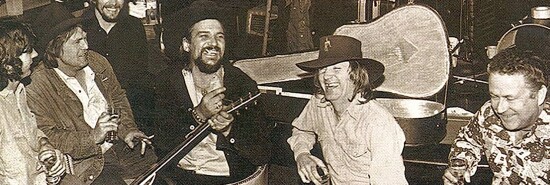

The 50th anniversary of when Waylon Jennings and Billy Joe Shaver created outlaw country

Christopher J. Scalia

Waylon Jennings was restless. Although he’d released a number of hits since signing with RCA in 1964, by the early 1970s he’d grown frustrated with the label’s demands. His producer, the legendary Chet Atkins, was a major force behind the sound known as countrypolitan, a highly produced style featuring orchestral arrangements and prominent backup singers as well as a large stable of session musicians. This style had enormous crossover appeal, but if you listen to Jennings’s overproduced cover of “MacArthur Park,” you can hear why the singer wanted more creative control.

RCA began to relent in 1972. First, they gave Jennings more say in song selection. Then, they let him record with his touring band instead of session musicians, and even produce the albums himself. With this new artistic freedom, he replaced the bright shine of countrypolitan with a stripped-down, back-to-basics sound.

HOW TO CARVE A BOOMER MOUNT RUSHMORE

Honky Tonk Heroes isn’t the first outlaw album, but it is the first truly great one. What set it apart was that nearly all of the songs were written by a cantankerous Texan named Billy Joe Shaver. The Ballad of Billy Joe goes something like this: a high school dropout, Shaver spent time as a child in the honky-tonk bar where his mother worked. He picked cotton, served in the Navy, and lost two fingers in a sawmill accident before finally venturing to Nashville when he was nearly 30. His early songs were recorded by Bobby Bare and Kris Kristofferson.

When Jennings first heard Shaver play in 1972, he vowed to record an entire album of Shaver’s material. Problem was, only Shaver remembered the promise. He pestered Jennings for months, finally confronting him during a recording session. “I got these songs,” he told Jennings, “and if you don’t listen to them, I’m going to kick your ass right here in front of everybody.” Even after Jennings agreed, Billy Joe was still ornery and mean. Sitting in on a recording session, Shaver grew so frustrated with the star’s interpretation of a number that he demanded, “What are you doing to my song?”

“You are going to get your ass out of here and stop bugging me,” Jennings warned. “I love your songs, but I’m starting not to like you worth a damn.”

Shaver’s songs made up for his outbursts. According to Jennings, “Billy Joe talked the way a modern cowboy would speak, if he stepped out of the West and lived today. He had a command of Texas lingo, his world as down to earth and real as the day is long.” But if Shaver’s language was down-home, his phrasing and syntax were often more complex, occasionally sounding like one of David Milch’s Shakespearean dudes from Deadwood.

Among the album’s strengths is its thematic unity: nearly all of Shaver’s compositions are world-weary expressions of an outsider’s rambling life, homesickness and restlessness, passion and regret. The album begins with its title track, which is based on Shaver’s days at his mother’s bar. Gentle guitar chords introduce the mesmerizing opening verse:

Low-down leavin’ sun / Done did everything that needs done.

Woe is me, why can’t I see? / I’d best be leaving well enough alone.

A fiddle joins in time for the narrator to offer a comic moment of self-realization:

Them neon light nights, couldn’t stay out of fights / Keep a-haunting me in memories.

Well there’s one in every crowd, for crying out loud / Why was it always turning out to be me?

The song has only four verses, with two of them repeated three times, but it doesn’t seem repetitive because Jennings’s arrangement and vocals pick up complexity and intensity at every iteration.

The sense of helplessness against bad decisions returns in “Black Rose,” whose chorus begins: “The devil made me do it the first time. / The second time I done it on my own.” This song also includes a memorable description of a dangerous but irresistible woman, “built for speed with the tools you need / to make a new fool every day.” “Ain’t No God in Mexico,” despite its title, offers a vision conservatives could appreciate, expressing healthy skepticism in the utopian belief that “A new day’s coming on / Where the women folks are friendly / And the law leaves you alone.”

Bob Dylan recently called another Shaver song, “Willy the Wandering Gypsy and Me,” “a riddle … the further you go in, the stranger it gets, seems to have ulterior motives.” The strange syntax of the opening verse establishes that confusion:

Three fingers whiskey pleasures the drinkers / And moving does more than the same thing for me.

Willy he tells me that doers and thinkers / Say movin’ is a closest thing to being free.

Willy’s an awful influence on the narrator: “my woman’s tight with an overdue baby / And Willy keeps yelling, ‘hey Gypsy let’s go’.” You can guess whether the narrator accepts the invitation.

Shaver’s songs suit Jennings perfectly. His weathered voice makes every line convincing, and he navigates Shaver’s unusual phrasing perfectly. The album’s weakest song (“We Had It All”) is its lone exception to the outlaw ethos, and the only one Shaver didn’t write. RCA added it because they thought it would make a good lead single. It didn’t — the follow-up single, the Shaver-penned “You Ask Me To,” fared much better on the charts.

According to country-music author Michael Streissguth, Honky Tonk Heroes “christened country music’s outlaw era.” It also positioned Waylon for a string of hit albums and No. 1 singles over the rest of the decade and set a path for other outlaw musicians. Willie Nelson would gain similar creative control for his classic 1975 album Red Headed Stranger. That same year, Jennings had another No. 1 country hit with the ultimate outlaw anthem, “Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way” — even as Glen Campbell went to the top of both the pop and country charts with the ultimate countrypolitan anthem, “Rhinestone Cowboy.” In 1976, the album Wanted! The Outlaws featured songs by Jennings, Nelson, and others and spent six weeks at No. 1, and when Waylon & Willie teamed up for a song, “Mamas Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to be Cowboys,” it topped the charts in 1978. The outlaw spirit rode into the next decade, too: Seven years after Honky Tonk Heroes, Jennings had another No. 1 with the theme song for America’s favorite show about good ol’ boys in trouble with the law, The Dukes of Hazzard.

Not that you need to know all of this context to enjoy Honky Tonk Heroes. One of its charms is that its joy is immediate, even if Shaver’s lyrics aren’t necessarily straightforward. That’s why it still sounds fresh after 50 years and remains an inspiration for country musicians who resist Music Row’s conventions.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Christopher J. Scalia is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and co-editor of Scalia Speaks: Reflections on Law, Faith, and Life Well Lived (Crown, 2017).