Two new books cover Manhattans clutch of ‘supertalls’

Anthony Paletta

The tallest buildings in the world used to be instantly famous, such as the Eiffel Tower (originally intended as a temporary installation), the Sears Tower, or, of course, New York‘s Empire State and the Chrysler buildings, each of the latter two built to outdo the other. “Supertalls” lately rarely hold the crown for that long, and since the Burj Khalifa, you may not even have heard of the latest superlative skyscraper from the Middle East or Asia. After an indolent stretch, New York is back in that groove lately, with some true stratosphere-scratchers around the southern edge of Central Park.

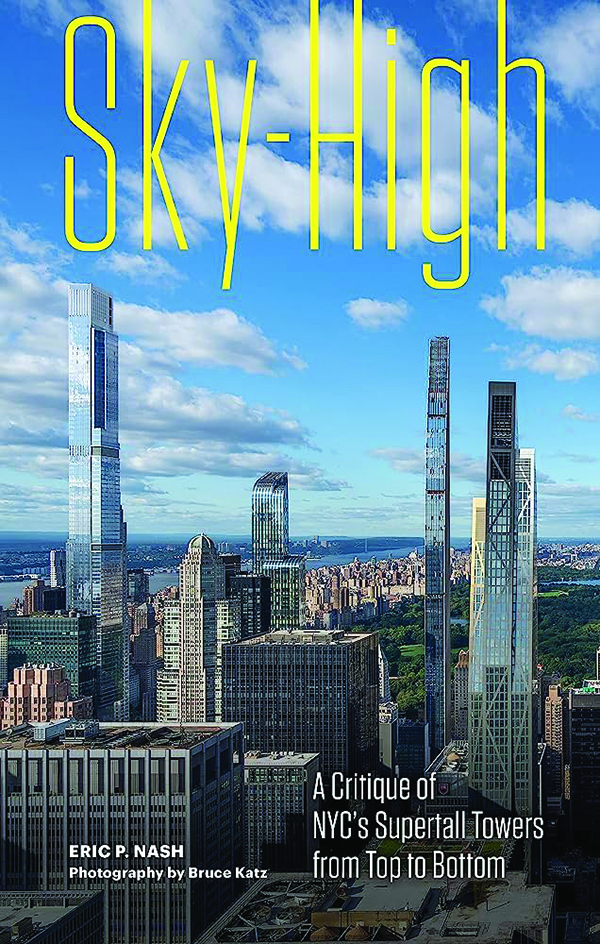

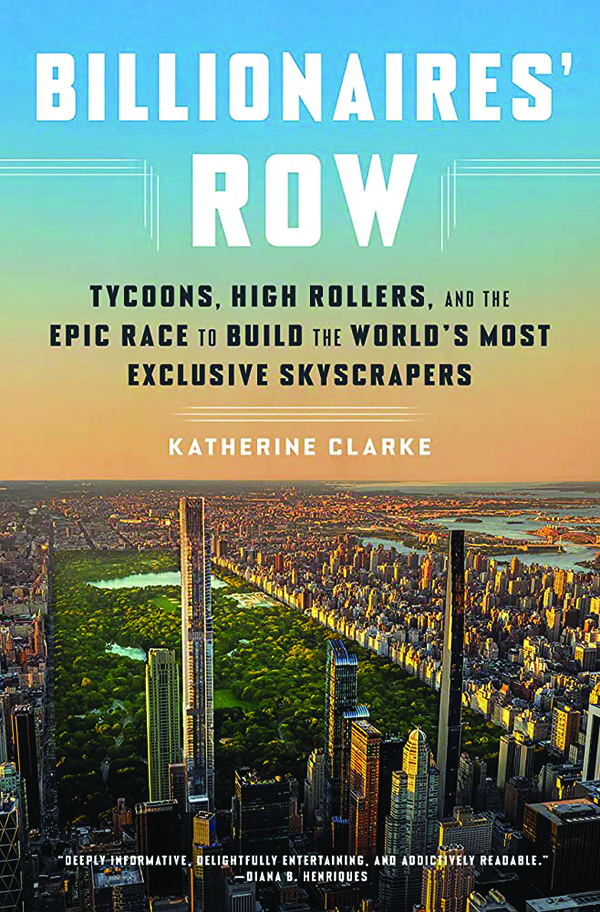

On the subject of New York supertalls, two nonfiction books have appeared virtually simultaneously: Eric P. Nash’s Sky-High: A Critique of NYC’s Supertall Towers from Top to Bottom and Katherine Clarke’s Billionaires’ Row: Tycoons, High Rollers, and the Epic Race to Build the World’s Most Exclusive Skyscrapers. Nash was a writer for the New York Times and an author of several previous books on architecture, and Clarke is a real estate writer for the Wall Street Journal. Nash’s account is largely one focused on design and takes as its focus a wide range of Manhattan supertalls.

ARCHDUKE’S EDUARD VON HABSBURG’S ADVICE TO MODERNITY

The threshold for this designation, according to the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, is 984 feet, and New York has 17 that clear this mark, more than any other city on Earth. They tend to make ordinary skyscrapers look stocky. Nash writes, “In comparison, the supertall is a supermodel, a Giacometti, an attenuated cruet of the old cartoon character Olive Oyl.” Their proportions are preposterous. 111 West 57th Street has a width-to-height ratio of 1:24. It contains 91 stories at 1,428 feet of height.

Nash’s is a deft explanation of their assembly, from the metaphysical games of air-rights purchases to secure approval for their height (“a three-dimensional chess game, played mostly with empty space”) to the improvements in concrete and steel necessary to hold these things up.

The most intriguing or unsettling element of these towers is the certainty that they will move. None of them are at risk of falling down, but they are certain to wobble due, as Nash explains, to “vortex shedding, a principle of fluid dynamics wherein air flowing past a bluff, vertical, sheer surface creates low-pressure vortices eddying from the sides. This produces uneven pulsations downwind, causing the building to rock from side to side like a palm tree buffeted in a storm.”

One solution is mass dampers, generally liquid weights atop the tower that swing against the sway — the one at 111 West 57th weighs 730 tons. There are other partial mitigations: Rafael Viñoly carved voids into his 432 Park to reduce this pressure by allowing air to pass through. These towers are often rife with unusable space. Adrian Smith and Gordon Gill’s Central Park Tower, a condo building, contains 33 floors without any residences.

Many of these residences are, of course, also unoccupied. Investment trophies for plutocrats around the world, as Nash writes, “in what amounts to a safe-deposit box in the sky, mostly with foreign equity in untraceable, nested shell companies.” They do offer a simulacrum of a yard, with Central Park as “a tapis vert worthy of the Sun King.”

His survey encompasses a number of these that don’t receive as much attention as the 57th Street bigwigs: One Vanderbilt, 15 Hudson Yards, and DeKalb in Brooklyn. There’s a common tendency to dismiss these as symbols of obscene wealth, which isn’t exactly wrong, but the Chrysler and Woolworth buildings were not built by community organizers. His views on the aesthetics of these buildings are generally sound. Some are great, and some are junk, but the balance of the former to the latter is probably better than most recent skyscrapers.

Clarke covers much of the same territory but digs far deeper into the bewildering bedrock of the financial underpinnings of these vanity symbols. Financing for these was undertaken in the transitional lending period post-Dodd-Frank, an era of seeking out ever more exotic-to-shady cash. The bridge and mezzanine loans financing these projects seem considerably more complicated than even cutting-edge engineering. No structural engineer is also trying to push you off a ledge, which many financial partners virtually are. Clarke expounds in admirable detail the unseen underbelly of complicated financial engineering, litigation, and “sabotage” that gets these things going.

Internecine lawsuits resulted. Merely getting started on these projects often took years, with property and air-rights assembly an excruciating process that could be stalled at length by a single holdout. Two of the Billionaires’ Row projects employ cantilevers built out over neighbors. One at Robert Stern’s 220 Central Park South cost an additional $300 million, a cost still regarded as tolerable. Chinese banks, Middle Eastern oil barons, and all sorts of characters got sewn into “Frankenstein’s-monster-like financing arrangements.”

And yet these projects did find buyers: The supertall condo boom, in contrast to more exclusive city co-ops, was one deliberately more open to the mega-rich from anywhere. A decade ago, as many as one-third of buyers were Chinese. There were otherwise Saudi billionaires, Los Angeles hedge funders, Russian oligarchs, Jennifer Lopez and Alex Rodriguez, and even Sting. The main requirement was that you have a lot of money, with individual sales pricing up to $240 million. Over time, some of these buildings grew irked by the public perception of housing mostly villains from the James Bond filmography and grew a bit more selective about who they were letting in. Other developments altered the buying base, too: Beijing’s “anti-corruption campaign” hit big-dollar purchases in the United States by Chinese buyers, and U.S. sanctions in the wake of the first Russian invasion of Ukraine have at least somewhat made it more difficult for oligarchs from that country to stash cash. And, of course, there are just simple market fluctuations.

As for the habitats themselves, life was not always heavenly up there. Unfortunately, the most attractive of these buildings, 432 Park, seemed to have the most problems. Promptly upon the condo board being turned over to residents in late 2020, the residents filed a lawsuit against the owners, citing “more than 1,500 alleged construction and design defects.” These problems included massive leaks and elevators out of service for hours. Clarke writes, “It compared the sound of dropping garbage into the trash chute to the detonation of a bomb.” Does that happen at your place?

And yet these buildings have all basically succeeded somehow. Many have made less money for their owners than expected, but they’re hardly suffering.

Even with a full accounting of their semi-sordid and absurd roots, it’s difficult not to admire the general idea of building taller, which is what the city has done. To achieve a “skyscraper that would fit in many Americans’ backyards,” Clarke writes, is something that would simply have been impossible for most of history. Not to mention that these property owners are pouring all sorts of cash into the city in property taxes — not a bad deal, especially if they never set foot in town.

The destiny of Manhattan has always been up, and the idea that this should be capped at any given year seems blasphemous. Together, these twin accounts tell the latest chapter in a great story of a great city.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Anthony Paletta is a writer living in Brooklyn.