Unearthing a family’s history after the Holocaust

Diane Scharper

In 1942, the Nazis arrested and deported thousands of French Jews to the Pithiviers detention camp. After a few months, detainees would go by train to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where they learned skills to use in Germany and thereby aid the war effort.

At least, that’s what Ephraïm and Emma Rabinovitch and two of their three children, Noémie and Jacques, believed. But they were deceived and died at Auschwitz.

THINKING DOUBLY HARD ABOUT GEORGE ORWELL

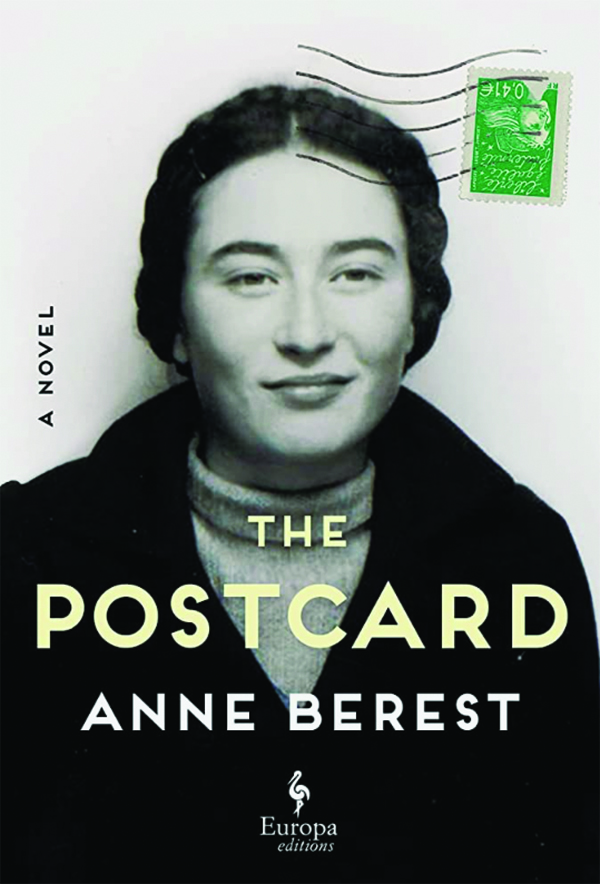

Myriam, the oldest of the siblings, was the family’s sole survivor. Some say her survival was miraculous. Her granddaughter, Anne Berest, sees Myriam’s survival as a series of lucky breaks. Just how lucky is the subject of The Postcard, Berest’s compelling autobiographical novel, which was written with the help of her mother’s notes and insights. Berest, the award-winning French author of six books, rightfully gives most of the credit for the book to her mother, who, after receiving the anonymous postcard of the title in 2003, has been collecting notebooks filled with family information for many years. Blending what Berest and her mother, Lélia, learn about their ancestors with facts from history books, articles, archives, letters, and information gathered from extended family, friends, and neighbors, Berest creates what she calls a “true novel.”

For most readers, the Holocaust victims’ names and faces have blended into blurry newspaper photographs of starving shapes with shaved heads wearing dirty striped pajamas and packed together in a room with bunk beds. But for Berest, the Rabinovitches are not merely starving figures and names on Holocaust lists. They are members of her family. That central fact propels her story, giving it an urgency that makes the book impossible to put down. Told in four sections, the novel mostly comes together like a collection of interlocking essays composed of narratives, emails, and meditations on the meaning of family and of being Jewish in today’s world.

The story begins in 1919 in Riga when Nachman, the family patriarch, gathers his adult children and his grandchildren for Pesach and tells them antisemitism is on the rise and that they are no longer safe in Latvia, where they have moved after leaving Russia. They must leave Eastern Europe now. He suggests they move to Palestine or America. This way, they could escape the coming onslaught of persecution.

One of his sons, Ephraïm, refuses, adamant about staying put with his wife, Emma, pregnant with Myriam. Ephraïm, who is nonobservant, sees Judaism as irrelevant and believes that since he doesn’t practice his religion, he and his family will be spared. But he chafes under new laws targeting Jews and decides to follow his parents to Palestine. Ephraïm, an engineer and an inventor, soon tires of working in his father’s orange plantation and moves his wife and three children to Paris.

Insisting that religious observance will backfire, he refuses to let his wife practice her Jewish faith and will not permit his son to receive his bar mitzvah. He applies for French citizenship and is refused — sounding an ominous note. It is one he doesn’t recognize, although readers do.

As Anne and Lélia discuss Ephraïm’s response (or lack thereof) to antisemitic laws, they touch on the essence of the story: “It’s horrible to think of Ephraïm being obedient to the very government planning his destruction.”

“But he didn’t know that,” Lélia says. “He couldn’t even conceive of the possibility.”

His perspective adds to the story’s dramatic irony, which increases as the plot develops and Ephraïm becomes afraid for his safety in Paris. Moving his family to their country home in the village of Les Forges in Normandy in southern France, he thinks all will be well.

But his 19-year-old daughter, Noémie, and 16-year-old son, Jacques, are arrested and taken away to Pithiviers and then sent to Auschwitz. Their parents try to find them and are also arrested. Myriam, who has recently married Vincente, a Frenchman, and lives in Paris, is not on the list to be deported and is safe for the moment.

This is the mostly true story at the heart of The Postcard. First published in France in 2021, the novel received several prestigious awards, including the Elle Readers Prize, and is now out in an English translation by Tina Kover.

The postcard itself, the fulcrum of the story, contains a photograph of the Opéra Garnier, a Parisian gathering place for many Nazis. On the back of the card are the names Ephraïm, Emma, Noémie, and Jacques — members of Myriam’s family. Lélia finds the postcard troubling and tells her daughter about it.

As Berest researches the postcard’s origin, she becomes intrigued by her grandmother, Myriam, and her maternal ancestors. Berest and her sister, Clare, had written an earlier biography about their paternal grandmother, Gabriele Picabia, who was married to the artist Francis Picabia and was also the mistress of Marcel Duchamp. Although The Postcard would be more difficult to research because most of the primary characters were deceased, Berest is determined to learn about their lives and personalities. She attempts to recreate them in this novel and describes her search, the information she finds, her analyses, and interviews, making The Postcard both a story and a narrative about writing the story. Everything becomes fodder.

The storyline zigzags back and forth over time and through the extended Rabinovitch family. It uses broad brush strokes to paint the lives of Ephraïm, his parents, siblings, wife, and children in the early 20th century. Then focusing on the years from 1942 to 1945, the book slows down, increasing the tension with small details that suggest the tragic outcome of the story.

It also takes a penetrating look at Myriam’s attempts after the war to find her parents and her siblings. After Myriam dies from old age, her daughter, Lélia, and granddaughter, Anne, take up the cause. They learn that Myriam’s guilt at being alive after her family died gnawed at her relentlessly. In addition, she never stopped looking for her family. Even as she was losing her memory, she wrote down their names so she could keep them close.

Some of the novel’s most searing moments concern Myriam’s daily trips to the train station, where she waits as trainloads of survivors arrive in Paris. She studies faces coming off the train, hoping that one of them would be her mother, father, sister, or brother. She pastes pictures and descriptions of her family on the walls of public buildings. She looks at photos of the missing and lists of names.

She leaves her toddler daughter, Lélia, in the care of a guardian and spends several years traveling to England, Germany, and various places in France, trying to find news of her family. Devastated that she has failed, she refuses to discuss her past, leaving her daughter hungry for information. Berest’s dramatic writing style brings the story and the loss it portrays alive, inviting readers to remember those who died in the Holocaust, just as she has remembered them in writing this book.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Diane Scharper is a poet and critic. She teaches the Memoir Seminar for the Johns Hopkins University Osher Program.