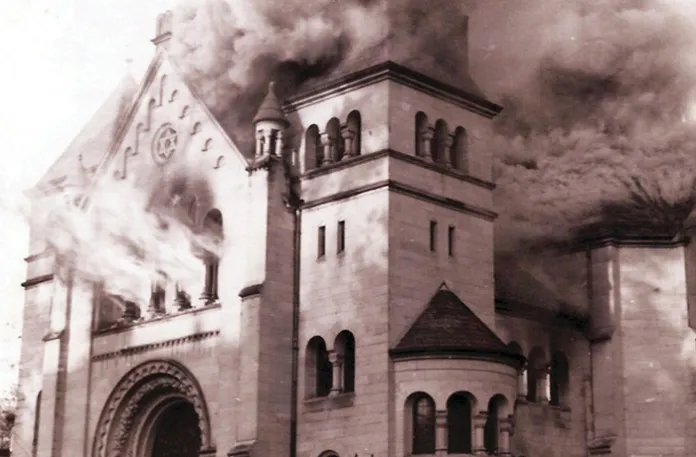

On the night of Nov. 9, 1938, flames lit up the streets of Nazi Germany and Austria. Synagogues burned. Windows shattered in Jewish homes and businesses. Mobs cheered as fire departments stood by, instructed to intervene only if the blazes threatened Aryan property. By dawn on Nov. 10, nearly 100 Jews lay dead, beaten or shot in the chaos. Another 30,000 had been rounded up and sent to concentration camps. The event, dubbed Kristallnacht for the shards of glass carpeting the sidewalks, marked a turning point. It signaled the Nazi regime’s shift from discrimination to outright violence against Jews.

Historians note that the pogrom was orchestrated by the Nazi leadership, with Joseph Goebbels playing a key role in inciting the violence following the assassination of a German diplomat by a Jewish teenager in Paris. Over 1,000 synagogues were torched, and 7,500 Jewish businesses vandalized. In the aftermath, Jewish communities were fined 1 billion Reichsmarks for the damage, further entrenching their economic isolation.

For survivors and their descendants, attacks on synagogues evoke that terror. These buildings stand as sanctuaries of faith and community. When they burn, the act strikes at the soul of Jewish existence, a reminder that hatred can erupt without warning. And now it is increasingly coming from less familiar sources, including Islamists and elements on the radical Left.

Almost nine decades later, on Jan. 10, 2026, fire again engulfed a synagogue in the diaspora. Beth Israel Congregation in Jackson, Mississippi, the state’s largest Jewish house of worship, went up in flames. Congregants woke to news of charred walls and a gutted interior. Stephen Pittman, 19, had allegedly poured gasoline inside and ignited it with a lighter. He fled but sought medical treatment for burns on his hands and ankles. He was arrested at a hospital after his father alerted the FBI that he had confessed to targeting the synagogue for its “Jewish ties.” The attack left the building heavily damaged, forcing the congregation to relocate services. “This was a deliberate, targeted attack on our community,” the synagogue’s leader, Rabbi Jeremy Simons, said to members in a statement.

The arsonist has since been charged with maliciously damaging a building by fire or explosive. He appeared in court with visible bandages and a Bible on the table before him. He pleaded not guilty, but a federal judge denied bond, citing the severity of the crime and his history.

The fire reduced parts of the synagogue to rubble, yet one item remained untouched: a Torah scroll brought by Holocaust survivor Gilbert Metz in 1992. Community leaders, including Gov. Tate Reeves (R-MS), condemned the act and pledged support for rebuilding.

A legacy of flames

Beth Israel has endured fire before. Founded in 1860, the congregation has deep roots in Mississippi’s Jewish history. Members built lives in Jackson amid the South’s turbulent past. In the 1960s, during the civil rights era, the synagogue drew the ire of white supremacists. Rabbi Perry Nussbaum, a vocal supporter of integration, preached equality from the pulpit. He helped found the Committee of Concern, raising funds for black churches burned by the Ku Klux Klan, which responded with violence. On Sept. 18, 1967, dynamite exploded at the synagogue’s new building on Old Canton Road. The blast tore through the structure just after midnight. No one was inside, but the damage ran deep. Two months later, on Nov. 27, 1967, the KKK bombed Nussbaum’s home. Again, the family escaped injury. The attacks formed part of a broader campaign against Jewish leaders seen as allies to black activists. Thomas Tarrants, a Klan member convicted in the bombings, later renounced his views and became a minister. But the scars remained. Sam Bowers, the imperial wizard of the White Knights of the KKK, ordered the hits, viewing Nussbaum as a threat to segregation.

Beverly Geiger Bonnheim, a congregant in 1967, was 17 at the time. She recalled the fear in a recent interview: “It was terrifying. We knew we were targets.” Now 75, she watched the 2026 arson unfold. “It’s like deja vu,” she told reporters. The congregation rebuilt after 1967, strengthening its resolve. It hosted interfaith events and preserved artifacts from the bombing. The Mississippi Freedom Trail marks the site as a reminder of hate’s cost. Yet the cycle repeated. Pittman’s online world revealed clues to his motives. Social media posts showed antisemitic rhetoric, echoes of age-old tropes. Investigators traced his path: He allegedly entered through a side door, doused books in the library, and set the fire. The blaze destroyed Torah scrolls and prayer books. Community leaders vowed to rebuild. “We will not be intimidated,” said Stuart Rockoff, executive director of the Mississippi Humanities Council. The Jewish Federations of North America mobilized aid, drawing parallels to the 1967 recovery.

Surging hate in the streets

Antisemitic acts have surged across the United States in recent years. In New York City, the epicenter of Jewish life in America, police logged hundreds of bias incidents targeting Jews in 2025, accounting for 57% of all hate crimes reported citywide despite Jews comprising only about 10% of the population. Attacks occurred nearly every day, ranging from subway assaults to synagogue vandalism incidents. In January, two teenagers were arrested after Nazi symbols were painted on playground equipment at Gravesend Park in Brooklyn. Crews scrubbed the graffiti, but the message lingered. Gov. Kathy Hochul (D-NY) called it a “depraved act of antisemitism. In a children’s playground where our kids should feel safe and have fun.”

The spike followed patterns seen nationwide. The Anti-Defamation League tracked approximately 9,300 antisemitic incidents in the U.S. in 2024, a record high. Numbers dipped slightly in 2025 but remained elevated, with a portrait of experiences showing higher rates of harm among those directly affected. College campuses became flashpoints. Hillel International reported a record 1,012 antisemitic incidents on campuses during the 2024-2025 academic year, the highest since tracking began in 2019. Protests over Middle East conflicts sometimes veered into harassment. Jewish students reported slurs and exclusion. In Albany County, a man faced hate crime charges for antisemitic threats against a county employee. In January, New York City Council Speaker Julie Menin unveiled a five-point plan to combat rising antisemitism. It included increased patrols and education programs.

Incidents proliferated beyond New York as well, from Boulder, Colorado, to California, where universities faced investigations for failing to address harassment. In February 2025, the Education Department probed five institutions for widespread antisemitic incidents. Nationwide, the ADL noted that anger at Israel drove much of the 2024-2025 increase, which begs the question: If it’s a foreign military operation that’s been what has provoked the recent rise in antisemitism, then why haven’t student protesters and others directed their vehemence at Russian Orthodox churches and at Persian cultural institutions after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Iran’s brutal crackdown of domestic dissent, which, by some estimates, has left tens of thousands dead? Why have only Jews been the recipients of such unique hate? Once again, we’re being forced to ask ourselves, as we have done so often in our history, why us?

Shadows across borders

The resurgence extends beyond U.S. shores. Globally, antisemitic incidents climbed 7.5% from January to November 2025, totaling 6,333 cases. The Combat Antisemitism Movement documented monthly spikes: 694 in August alone, averaging 22 per day, up 15.7% from the previous year. Twenty people died in antisemitic violence worldwide that year. Australia, as I chronicled in these pages, experienced a deadly attack during Hanukkah, which officials described as the worst antisemitic incident in the nation’s history. In Europe, France and Germany reported sharp increases. Synagogues faced vandalism. Jewish schools heightened security. The United Kingdom logged a 90% rise in incidents from 2021 to 2023, a trend that continued into 2025, with 572 online cases in the first half alone. France recorded 1,676 incidents, a 284% increase from the prior year, with physical assaults rising from 43 to 85. Incidents in Germany climbed to 3,614. In Canada, reports indicated a surge of over 200%, while Argentina noted increases to 598 cases. Brazil experienced a 311% jump, reaching 1,774 incidents. South Africa and Mexico also faced dramatic rises, with incidents tripling in some cases.

Middle Eastern state propaganda fueled much of the rhetoric. Iran broadcast antisemitic content through media outlets. Online, bots amplified hate speech in ways that bridge far-left and far-right ideologies. Islamist-motivated acts increased by 44% compared to the previous year, now accounting for 13% of all documented incidents. The ADL’s 2025 review highlighted resilience amid the crisis: communities rallied, governments responded. Yet the numbers painted a grim picture. “Antisemitic discourse no longer needs justification,” a Ynet analysis noted. It spreads unchecked on social platforms. The Global Terrorism Index tied the surge to lone-wolf actors who are believed to be responsible for 93% of Western attacks in recent years. The J7 task force’s annual report detailed unprecedented levels across seven major Jewish communities, with surges up to 317% in some countries since 2023. Reports described the wave as a “tsunami of hate,” prompting enhanced security measures and international calls for action.

Washington’s response

Thankfully, the Trump administration has taken some forceful steps to address the threat. In December 2019, President Donald Trump signed Executive Order 13899, directing federal agencies to combat antisemitism on campuses. It adopted the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s definition of antisemitism. In January 2025, Trump issued Executive Order 14188, aiming to enforce Title VI of the Civil Rights Act more rigorously against discrimination and building on the 2019 policy in response to ongoing conflicts. The order reaffirmed the administration’s commitment to combating antisemitism amid rising incidents in the U.S. and around the world.

In February 2025, the Justice Department formed a task force to root out antisemitic bias in education, announcing that its first priority would be attempting to eradicate hate in schools and colleges. Investigations followed complaints at universities, with the task force visiting 10 campuses that had experienced antisemitic incidents. In March, the task force met with leaders in four major cities affected by antisemitism, including Los Angeles, to discuss local responses. The Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights sent letters to 60 universities in March warning of enforcement if discrimination persisted. Trump met with Jewish leaders, emphasizing his commitment to protecting their communities. Internationally, the administration has urged our allies to adopt similar definitions.

The Antisemitism Awareness Act of 2025, which was introduced in February and passed the House, aims to provide statutory authority for these measures and to strengthen counterterrorism efforts. The bipartisan measure codified the IHRA definition for federal use. Training for federal law enforcement expanded, ensuring that antisemitism would be addressed in military and veteran programs. By mid-2025, the task force canceled $400 million in grants to noncompliant institutions such as Columbia University, underscoring that the administration would not hesitate to hold recalcitrant actors accountable. The act required annual reports on antisemitism trends, which may lead to increased funding for security at Jewish institutions. Jewish organizations such as the ADL have commended the legislation for providing clearer guidelines in investigations. Congressional debates highlighted divisions, with some Democrats expressing concerns over the possible suppression of legitimate criticism.

NEW YORK’S RADICAL NEW CHAPTER: ZOHRAN MAMDANI TAKES THE HELM

This semester, I’m teaching an undergraduate course on the history of antisemitism at Rutgers University. The syllabus covers two millennia of pain and persecution, from charges of deicide to medieval blood libels, the Dreyfus Affair, the Holocaust, and beyond. The problem is that I wish it were just history. Unlike courses on ancient Greece or Rome, this is a history that is now bleeding into the present. Attacks such as the Mississippi synagogue arson remind us that if William Faulkner’s famous quote, “the past is never dead; it’s not even past,” could ever be applied to a subject, it’s this one.

My goal with the course is to foster awareness of antisemitism’s origins, signs, and endurance. I hope that by the end of the semester, my students will be able to identify this hatred’s tropes, trace its sources, and understand its persistence. At the same time, I hope we’ll work together to build bridges across faiths and turn awareness into action for a more tolerant society. Perhaps then, we’ll finally be able to relegate antisemitism to history — and only history.

Daniel Ross Goodman is a Washington Examiner contributing writer and the Allen and Joan Bildner Visiting Scholar at Rutgers University. Find him on X @DanRossGoodman.