Peter Matthiessen was a towering figure in 20th-century American letters. He was a naturalist, environmentalist, Zen Buddhist priest, teacher, world traveler, CIA agent, and a mystic. He was one of the first writers to be concerned about the extinction of animal species, the care of the environment, and man’s exploitation of indigenous people. His efforts earned him two National Book Awards, one for fiction and one for nonfiction.

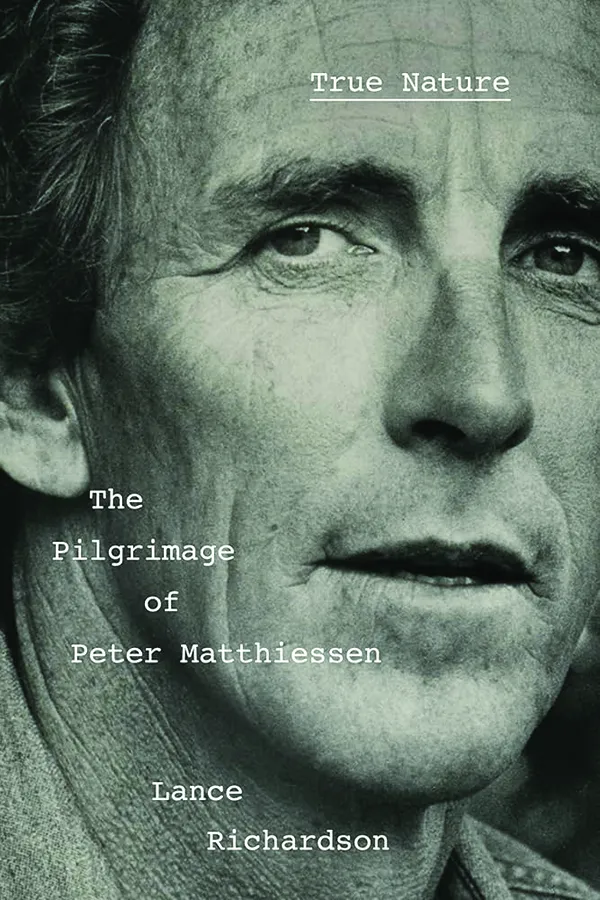

Lance Richardson’s door-stopper biography, True Nature, the Pilgrimage of Peter Matthiessen, is the first biography written about him, though a documentary appeared in 2009. Collecting excerpts from newspaper articles, letters, memoirs, and books highlighting Matthiessen’s life events, philosophy, and writing, Richardson paints a vivid portrait.

Born in 1927 to a wealthy family, Matthiessen died in 2014 at 86. He grew up in New York and in rural Connecticut, on 47 acres of land where he and his brother, Carey, watched birds and collected copperhead snakes. His mother’s bird feeder fascinated Peter, who dog-eared half a dozen copies of the Peterson Field Guide to the Birds. One of his favorite books was Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, particularly the scene where Mole and Ratty encounter the nature god, Pan, described as an “august Presence” bathed in light and silence. Years later, Matthiessen remembered the chapter as containing a “more profound manifestation of mystical experience than almost anything to be found in the religious literature.”

He was inspired by his father, Erard Matthiessen, who studied architecture at Yale. Erard was also a nature lover and conservationist who served as vice president of the National Audubon Society. When he retired from his work as an architect, he devoted his time to nature conservation and environmental education.

At 15, Matthiessen began “scribbling” essays and poetry, saying that it “restores your balance and your sanity.” He became chairman of the school literary magazine and received an award for his writing.

He followed his father to Yale, but he majored in English, taking numerous courses in biology and ornithology. He also co-wrote a hunting and fishing column for the Yale Daily News. He began writing short stories, and one of them, “Sadie,” won the prestigious Atlantic First Award. Spending his junior year in Paris, he studied at the Sorbonne.

He left Yale to marry, return to Paris, and work undercover for the CIA using Race Rock, his 1954 first novel, as a cover for his espionage activities. As further cover, he co-founded The Paris Review with George Plimpton, whom he knew from his days at St. Bernard’s School. After his first marriage ended in divorce, he married Deborah Love, who introduced him to Zen. When she died, he married Maria Eckhart Koenig, who cared for him in his final years.

He wrote over 30 books. Although he wrote mostly nonfiction, he considered himself a novelist, saying he received the most satisfaction from creating fiction. His novels began with a “gritty, primordial feeling,” which he wanted readers to remember even if they forgot plot and characters. He held that it was very important that “details are chosen in such a way that effects transcend the mere parts much as intuitive knowing transcends mere logic.”

His most celebrated novels were At Play in the Fields of the Lord, Far Tortuga, and Shadow Country, which won a National Book Award. His travel journal, The Snow Leopard, also won a National Book Award. He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1974. His final novel, In Paradise, set during the Holocaust, came out a few days after his death on April 5, 2014.

Infusing everything was his pursuit of a transcendent being. He didn’t call this God. He wasn’t even sure that he believed in a God, but he believed that there was “something there,” a creating force in everything we see. He said in an interview that he had many “experiences with it.”

While onboard the USS Joseph Dickman in 1945, for example, he faced a powerful Pacific Ocean storm. As he would explain years later, the wind, waves, and water crashed across the deck, inundating him until he felt himself one with the maelstrom. “Overwhelmed, exhausted, all thought and emotion beaten out of me, I lost my sense of self, the heartbeat I heard was the heart of the world, I breathed with the mighty risings and decline of the earth, and this evanescence seemed less frightening than exalting.”

This event would become the stimulus for much of Matthiessen’s life and work. As Richardson describes it, Matthiessen “was overcome with awe … he was given another way of seeing the world. [It] was a continuity with something more powerful than his own alienated self.”

Richardson notes that Matthiessen was drawn to writers such as Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Carl Jung, Annie Dillard, William Merwin, and others who had a mystical sense. The Mysticism that reverberates in Matthiessen’s work is associated with American Transcendentalism, which holds that an individual’s soul is a part of a larger spirit that unifies all existence. Matthiessen feels “moments of being,” when he “stops to marvel … becoming acutely aware of himself in the world, attuned to the minutia of some fleeting experience,” according to Richardson.

These moments, as Richardson explains in this evocative biography, would inspire Matthiessen to visit Auschwitz, climb mountains, pursue snow leopards, and descend into the ocean to study sharks. He would travel to Nepal, New Guinea, the Cayman Islands, Hawaii, and other diverse places in North and South America, Europe, Africa, and Asia, avidly listening for what he believed was the heartbeat of the world.

Diane Scharper is a regular contributor to the Washington Examiner. She teaches the Memoir Seminar for the Johns Hopkins University Osher Program.