During his two previous presidential campaigns and one term as president, Donald Trump was routinely accused by the national security “clerisy” of violating the norms of U.S. civil-military relations, especially those related to the political neutrality of the military. Of course, those norms had been eroding for some time, and much of the blame can be laid at the feet of the military. Things have only gotten worse recently. Several retired high-ranking generals and flag officers, including Army Gen. Mark Milley, the former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Marine Gen. John Kelly, Trump’s longest-serving White House chief of staff, have accused the former president of being a “fascist.”

Of course, the term is now little more than an epithet used to denote people or policies with which one disagrees. Democrats have been accusing Republican presidents and candidates of being fascists since at least Barry Goldwater. But it is unprecedented, and dangerous, for senior members of the retired officer community to engage in such vicious partisan attacks against a former, and possibly future, president using contemptuous language that violates the Uniform Code of Military Justice to which they are still subject.

For the most part, we can dismiss the charge of “fascism” as political hyperbole, but there is a more pertinent issue: Has the former president and current candidate violated the Constitution, which members of the military have sworn to protect?

Every person in the service of the federal government swears an oath to the Constitution. The president’s variant is specified in Article 2, Section 1, Clause 8. Members of Congress, military officers, and civil servants take a slightly different one, codified in Title 5, Section 3331 of the U.S. Code. All have the words “support and defend.” All but the oath of the president contains the “all enemies, foreign and domestic,” clause.

Domestic disorder and the use of federal forces

In the wake of the violent 2020 disorders that followed the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis, some called for then-President Trump to invoke the Insurrection Act. Sen. Tom Cotton (R-AR) made the case in an op-ed for the New York Times. Trump declared that “all Americans were rightly sickened and revolted by the brutal death of George Floyd” and said he was “mobilizing all available federal resources, civilian and military, to stop the rioting and looting to end the destruction and arson and to protect the rights of law-abiding Americans.”

Trump never invoked the Insurrection Act, but he said that though his “administration is fully committed that for George and his family, justice will be served,” he insisted that “we cannot allow the righteous cries and peaceful protesters to be drowned out by an angry mob. The biggest victims of the rioting are peace-loving citizens in our poorest communities, and as their president, I will fight to keep them safe. I will fight to protect you. I am your president of law and order and an ally of all peaceful protesters. But in recent days, our nation has been gripped by professional anarchists, violent mobs, arsonists, looters, criminals, rioters, antifa, and others.”

Later in his speech, Trump said he “strongly recommended” that state governors deploy the National Guard in sufficient numbers to establish “an overwhelming law enforcement presence until the violence has been quelled.” However, if “a city or state refuses to take the actions that are necessary to defend the life and property of their residents, then [he would] deploy the United States military.” In addition, Trump said he was “taking swift and decisive action to protect” the capital by “dispatching thousands and thousands of heavily armed soldiers, military personnel, and law enforcement offices to stop the rioting, looting, vandalism, assaults, and the wanton destruction of property.”

In response, Trump’s opponents, including a number of prominent retired high-ranking officers, criticized him for calling on governors to make arrests and employ force to disperse rioters and for deploying the District of Columbia National Guard to disperse protesting crowds near the White House. There are many reasons to avoid, if possible, the use of the military in domestic affairs, but in what respect did his actions violate the Constitution?

In the aftermath of this episode, Daniel Maurer, an Army lieutenant colonel and judge advocate, published an article noting that when retired senior military officers “publicly criticize current political affairs, they often invoke a defense of the Constitution. In light of their oaths and long careers devoted to supporting and defending the Constitution, this is not surprising. But there may be surprises in what, exactly, they choose to emphasize about this venerated charter.”

As Maurer wrote, “What exactly about the Constitution are these retired officers warning us might be weakened? Specific provisions in the Bill of Rights, like freedom of assembly? Specific structural provisions, like the proper subordination of the military to civilian control under Articles I and II, the president as commander-in-chief under Article II, or the police power of the states under the 10th Amendment? As a gentle nudge to those still on active duty as a reminder of their professional duties? Or, instead, are they using the Constitution — as a whole — as simply expressive of larger ideals and principles, the ‘American experiment,’ they find most exposed and vulnerable?”

In this case, much of the debate turns on the question of the nature of the disorder that rocked cities in the aftermath of Floyd’s death. Trump’s critics, including many of the retired military officers who objected to his call to use force against protesters, persisted in describing the protests as “peaceful” or “mostly peaceful.” Of course, the First Amendment to the Constitution protects free speech and the freedom of assembly. But what many people saw instead of peaceful protests was rioting and destruction of property. The question was the constitutionality of using military force to restore domestic order.

Domestic disorder and presidential authority to use force

Contrary to what many people believe, the Constitution itself does not prohibit the use of the military in domestic affairs. Although there are many good reasons to limit the use of federal troops in domestic law enforcement, the fact is that the U.S. military has intervened in domestic affairs nearly 200 times since the founding of the republic. Indeed, the U.S. Army Center of Military History has published three 400-page volumes on the use of the federal military forces in domestic affairs.

The authority of the president to use force in response to domestic disorder arises from the Constitution itself. Section 4 of Article 4 says: “The United States shall guarantee to every state in this union a republican form of government, and shall protect each of them against invasion; and on application of the legislature, or of the executive (when the legislature cannot be convened) against domestic violence.” Although the aforementioned First Amendment to the Constitution guarantees “the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances,” it does not protect riot, arson, and looting.

Under Article 2 of the Constitution, the president, as commander in chief of the Army and the Navy and of the militia (National Guard) when under federal control, has the authority to act against enemies, both foreign and domestic. Of course, as a federal republic, the first line of defense against domestic disorder is local law enforcement, supplemented as necessary by the resources of the states, including the National Guard. But if mayors and governors are unable or unwilling to quell disorder, the federal government has the authority to act.

The president’s basic constitutional authority was supplemented by the Insurrection Act of 1807, codified in Title 10 of U.S. Code, Sections 251-254, by which Congress explicitly authorized the Army to enforce domestic law in the event that “unlawful obstructions, combinations, or assemblages, or rebellion against the authority of the United States, make it impracticable to enforce the laws of the United States in any States by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings.” Although intended as a tool for suppressing rebellion presidents used this power on five occasions during the 1950s and 1960s to counter resistance to desegregation decrees in the South. It was also the basis for federal support to California during the Los Angeles riots of 1992, when elements of an Army division and a Marine division augmented the California National Guard. More recently, active-duty forces were deployed in response to natural disasters.

But what about posse comitatus? Doesn’t this limit the president’s authority? The undeniable fact is that most commentators do not understand the Posse Comitatus Act, codified in Section 1385, Title 18 U.S.C. The law does not constitute a bar to the use of the military in domestic affairs. It does, however, make sure that such use is authorized only by the highest constitutional authorities: Congress and the president.

In the Anglo-American tradition, the first line of defense in enforcing the law was the posse comitatus, literally “the power of the county,” understood to be the people at large who constituted the constabulary of the shire. When order was threatened, the “shire-reeve” or sheriff would raise the “hue and cry,” and all citizens who heard it were bound to render assistance in apprehending a criminal or maintaining order. Thus, the sheriff in the American West would “raise a posse” to capture a lawbreaker.

If the posse comitatus was not able to maintain order, the force of first resort was the militia of the various states, the precursor of today’s National Guard. In 1792, Congress passed two laws that permitted the implementation of Congress’s constitutional power “to provide for calling forth the militia to execute the laws of the union, suppress insurrections and repel invasions,” the “Militia Act” and the “Calling Forth Act,” which gave the president limited authority to employ the militia in the event of domestic emergencies.

In 1807, at the behest of President Thomas Jefferson, who was vexed by his inability to use the militia as well as the regular Army as well to deal with the Burr Conspiracy of 1806-07, Congress also declared the Army to be an enforcer of federal laws, not only as a separate force but as a part of the posse comitatus.

Accordingly, troops were often used in the antebellum period to enforce the fugitive slave laws and suppress domestic violence. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 permitted federal marshals to call on the posse comitatus to aid in returning a slave to his owner, and in 1854, Franklin Pierce’s attorney general, Caleb Cushing, issued an opinion that included the Army in the posse comitatus, writing:

A marshal of the United States, when opposed in the execution of his duty, by unlawful combinations, has authority to summon the entire able-bodied force of his precinct, as a posse comitatus. The authority comprehends not only bystanders and other citizens generally, but any and all organized armed forces, whether militia of the states, or officers, soldiers, sailors, and marines of the United States.

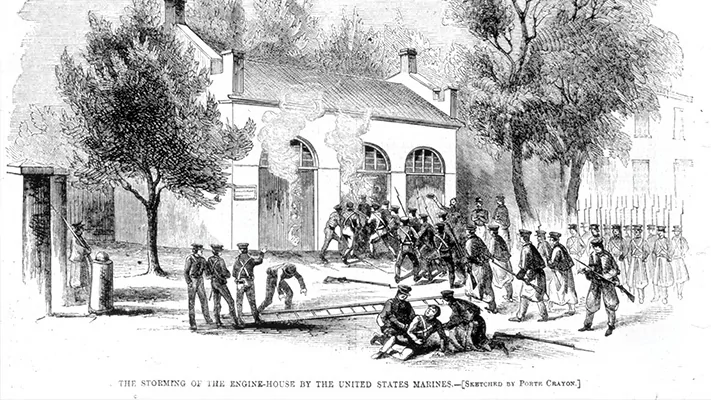

Federal troops were also used to suppress domestic violence between pro- and anti-slavery factions in “Bloody Kansas.” Soldiers and Marines participated in the capture of John Brown at Harpers Ferry in 1859.

After the Civil War, the U.S. Army was involved in supporting the Reconstruction governments in the Southern states, and it was the Army’s role in preventing the intimidation of black voters and Republicans at Southern polling places that led to the passage of the Posse Comitatus Act. In the election of 1876, President Ulysses S. Grant deployed Army units as a posse comitatus in support of federal marshals maintaining order at the polls. In that election, Rutherford B. Hayes defeated Samuel Tilden with the disputed electoral votes of South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida. Southerners claimed that the Army had been misused to “rig” the election.

Of course, some criticized Trump for threatening to use the National Guard “against the will of state governors.” But consider this example. After school integration was mandated by the Supreme Court in 1954, some Southern governors refused to execute the law. In 1957, Arkansas Gov. Orval Faubus deployed the National Guard to defy federal authority by preventing the integration of a high school in Little Rock.

President Dwight Eisenhower responded by placing the Arkansas National Guard under federal control and deploying soldiers of the 101st Airborne Division to enforce the law. In view of the invective directed against Trump for his threat to use federal troops to quell domestic disorder, it is interesting to note that in a letter to Eisenhower, Democratic Sen. Richard Russell of Georgia explicitly compared soldiers of the 101st Airborne Division to Hitler’s “storm troopers,” illustrating that the argumentum ad Hitlerum is nothing new.

‘National security community’ knows best: The perils of praetorianism

On the flip side of the coin, the military is obligated to obey the lawful orders of the commander in chief, but during the Trump presidency, members of the national security “community” often took it upon themselves to thwart the president’s policies. In the beginning, this activity was most prevalent among intelligence professionals, though it sometimes also involved active and retired military officers. Over the course of the Trump presidency, it was common for the president’s critics to claim that he was a threat to national security, whether because of “collusion” with Russia or controversy over the Ukraine affair, which led to his impeachment. But the same people who had once dismissed the idea of a “deep state” blocking the president’s policies as a dangerous conspiracy theory later came to support public opposition by unelected bureaucrats as a way to curb Trump’s actions.

In September 2018, the New York Times published an op-ed by an anonymous writer claiming to be a high-level member of the Trump administration. The thrust of the article was “that many of the senior officials in his own administration are working diligently from within to frustrate parts of his agenda and his worst inclinations.” He later followed up with a book. Observers speculated on the identity of the author, suggesting Defense Secretary Jim Mattis and chief of staff John Kelly. As it happened, the author was a relatively low-level staffer from the Department of Homeland Security.

Regardless of the writer’s rank, there is a name for this sort of activity: praetorianism. From the time of Augustus Caesar until Constantine, a corps of soldiers known as the Praetorian Guard protected the Roman emperor. Over time, the Praetorians became the real power in Rome, appointing and deposing emperors at will. In our time, praetorianism has come to mean despotic military rule, something associated with countries in which the army is the real power behind the government. Praetorianism would seem to be incompatible with republican government, although the attempted coup against President Charles de Gaulle in 1961 arose from a praetorian bent on the part of the French officers who sought to depose him over his intention to grant independence to Algeria.

Unfortunately, the idea that it was necessary to protect the country from a duly elected president has had its advocates from the beginning of Trump’s presidency. For example, right after his inauguration, Georgetown law professor Rosa Brooks, the author of How Everything Became War and the Military Became Everything, expressed an extreme version of this view. Writing in Foreign Policy, she remarked that Trump’s “first week as president has made it all too clear [that] he is as crazy as everyone feared. [One] possibility is one that until recently I would have said was unthinkable in the United States of America: a military coup, or at least a refusal by military leaders to obey certain orders.” A senior Pentagon appointee from 2009 to 2011, she continued that for the first time, she could “imagine plausible scenarios in which senior military officials might simply tell the president: ‘No, sir. We’re not doing that.’”

Many of the methods generals and other national security officials used to constrain Trump’s policy were not new. Although the U.S. Constitution provides the foundation for civilian control of the military, what this means in practice is far more complicated. As Samuel Huntington noted, the Constitution itself makes the practice of civilian control difficult as it divides it vertically between the state and federal levels and horizontally between the executive and legislative branches. Long practice has cemented the idea that in practice, the professional officer corps is to provide advice to civilian decision makers and then execute the policy. The military has no right to insist that its recommendations be accepted. Of course, the military is not obligated to follow an illegal order.

But exactly where to draw the lines that guide the behavior of the professional officer corps is difficult in practice. One of the many claims during Trump’s presidency that his critics raised was that he would involve us in endless military conflicts. What would the military do if the president ordered a nuclear strike against Iran or North Korea? Would the military act?

Of course, this raises a perennial question at the heart of civil-military relations: What do military leaders do if their advice is rejected? During Trump’s tenure, he and his military advisers clashed over such issues as the U.S. relationship with NATO, military actions in Afghanistan, intervention in Syria, and the appropriate response to domestic disorder.

One response to policies to which the military might be opposed involves subterfuge to undermine the president’s ability to implement his or her agenda: “slow rolling” execution, leaking to the press in an effort to undermine public confidence in the decision, and simply ignoring the policy. Bureaucracies have perfected these kinds of responses to policies with which they disagree, and those in the senior ranks of the military are often no different.

Slow rolling is a time-tested method. President Bill Clinton had to deal with slow rolling during the campaign in the Balkans. President George W. Bush and especially his secretary of defense, Donald Rumsfeld, did as well during the Iraq War. Trump also had to contend with slow rolling.

Every president has had to contend with leaks to the press, but no one has been victimized in this manner more than Trump. For example, after the 2020 election, the president asked for options, including an attack on Iran’s main nuclear site, following a report by the International Atomic Energy Agency that Iran’s uranium stockpile had reached a level 12 times higher than allowed under the nuclear accords. His advisers, including the secretary of defense, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and national security adviser, recommended against military action.

Both the president’s question and the advisers’ responses were reasonable. But the fact that this affair was leaked was not. On the one hand, it permitted the president’s detractors to portray him as seeking to provoke a conflict in his waning days in office. On the other, it possibly signaled to U.S. enemies that Trump, as a lame duck, would be unable to respond to aggressive provocations.

The final form of bureaucratic resistance to presidential policy is simply to ignore an order. In Trump’s case, the clearest example of this kind of action was ignoring his order to reduce U.S. military manpower in Syria. Ambassador Jim Jeffrey, who served as the special envoy in the fight against the Islamic State, acknowledged that his team routinely misled senior leaders about troop levels in Syria. “We were always playing shell games not to make clear to our leadership how many troops we had there,” Jeffrey said in an interview.

Milley has admitted that the military often disobeyed Trump’s lawful orders. For instance, in the days leading up to the Jan. 6 riot, Trump instructed Milley and acting Defense Secretary Christopher Miller to mobilize a substantial National Guard force to help keep the protest “safe.” Both ignored the order.

All of these actions by those trying to limit the president’s authority harmed civil-military relations by undermining trust. Trump’s critics emphasize his demand for loyalty, arguing that it was personal and political. But this misconstrues the nature of the loyalty Trump demanded: Every president has a right to expect that his or her subordinates will execute his or her policy decisions once they are made and certainly that they will not actively undermine those decisions.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Officers, of course, swear an oath to the Constitution, not to a person. But a president should be able to expect the loyalty of the officer corps to support an administration’s policy once a decision has been made, and it is the president along with Congress, not an imaginary “security community,” that has the constitutional authority to make national policy.

In the end, no matter what one thinks about Trump, we must ask ourselves: Is it a good idea for military officers and run-of-the-mill bureaucrats to form a phalanx around the duly elected president “for the good of the country”? Do we really want to normalize the view that unelected bureaucrats are the protectors of republican government? If so, we endanger the idea of republican government itself.

Dr. Mackubin Owens, a retired Marine and former Naval War College professor, is a senior fellow of the Foreign Policy Research Institute.