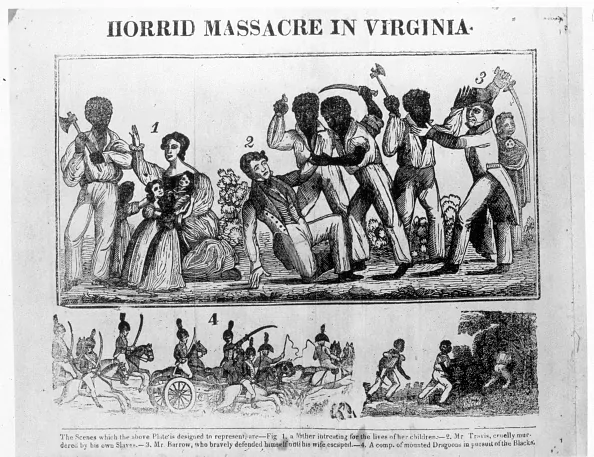

In the summer of 1831, judgment came for white slaveholders in Southampton County, Virginia. Nat Turner, a Methodist preacher, organized a war party of the enslaved and dealt a deadly blow against those holding them in bondage. Suddenly, what had once been a backwater near the Great Dismal Swamp became the site of the deadliest attack against slaveholders before the Civil War.

Using mostly axes and swords, Turner and his crew acted with remarkable efficiency, slaughtering men, women, and children in gruesome fashion at one house after another. Afterward, as he sat in a jail cell awaiting punishment for his rebellion, Turner told his captors about the visions he had been having for nearly a decade. “The Spirit that spoke to the prophets” had shown itself and, after two years of praying continually, had “fully confirmed me in the impression that I was ordained for some great purpose.”

As one historian noted, “fanaticism” became one of the charges against Turner. According to several letters in response to newspapers at the time, Turner was a “fanatic” who “had been taught to read and write and permitted to go about preaching the country” that, the author exclaimed, “was at the bottom of this infernal brigandage.” Another letter writer, maybe more concerned about his own soul, wrote that “those fanatical scoundrels” merely “pretended to be divinely inspired.”

In Nat Turner, Black Prophet: A Visionary History, Anthony Kaye, with help from Greg Downs, argues that Turner’s claim to be a prophet should be taken seriously. The author writes, “This book stresses the claim that Nat saw himself not just as a prophet, but as a particular kind of prophet, in the specific way early nineteenth-century evangelical Christians understood the Hebrew Bible prophets.” Turner and his followers went beyond the typical way modern people think about “prophets” such as Martin Luther King Jr. or Frederick Douglass, as forward-looking people. Instead, “Nat and some of his contemporaries … did not consider prophecy merely inspirational leadership. They considered it a marker of a specific fact: a prophet literally heard the voice of God and acted upon it.” Turner, after having his visions, had done the work of the Almighty.

Nat Turner, Black Prophet provides a necessary update on scholarship about the bloodiest slave insurrection in America before the Civil War. The book does remarkable work connecting Turner to the history of Christianity and slave insurrection in what’s now called the Atlantic World. The chapter leading up to and through the insurrection itself will keep readers turning the page, and Downs spares no details in describing the gory and brutal scene that was Nat Turner’s insurrection. The chapters following Turner’s capture and court trial succeed in revealing how American liberalism could create a government that enforced the enslavement of other human beings — all that was needed was a culture that would promote, or at least tolerate, the barbarity.

One minor quibble with Nat Turner, Black Prophet: A Visionary History is how it frequently straddles lines in its interpretations. “Perhaps” is certainly one of the most popular words deployed throughout the book. “Perhaps” Turner considered the Old Testament prophet Gideon. “Perhaps” Turner carried a sword to signify his leadership.

Though distracting, at times, this balancing act from Downs appears for two reasons. First, the obvious: Historians are not mind readers of the dead (or living) that they study. Getting into the head of Turner and his band requires reading into the very scant source material left to posterity. Unfortunately, seances to ask follow-up questions rarely get past peer reviews, and Kaye with Downs do fine work piecing together clues left in the historical record, tying them to the larger context of serious religious history.

Second, the remarkable: Gregory Downs accomplished a near-impossible task in publishing Nat Turner, Black Prophet. He deserves accolades for his commitment to the historical evidence and professionalism and, quite simply, for being a good friend.

Astute readers may notice that Nat Turner, Black Prophet has an unusual form for describing its authorship: Anthony E. Kaye “with” Gregory P. Downs. In the introduction, Downs writes that the book is “a story with its own complicated history. In June 2016, Tony Kaye asked me to prepare to take on the task he aimed not to leave me: the authorship of this book on Nat and his rebellion. Confronting his diagnosis of esophageal cancer, Tony was both sustaining his hope that he might survive its ravages and preparing for the possibility he might not.”

Kaye died 10 months later, leaving Downs with notes and outlines but little in terms of a draft manuscript. Nat Turner, Black Prophet’s introduction explains that “the book that follows remains Tony’s work, even though I have written or rewritten almost every word of it. The form of authorship on the title page reflects our understanding that this book would consist of his arguments and research, but my words.”

To explain how difficult this task appears to have been, imagine a game of telephone where you only have the context and motivations for the call rather than the call itself. Downs should be proud of his tribute to Kaye’s scholarship. He fulfilled the promise he made quite well and allowed Anthony Kaye to leave behind a book well worth reading.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Carl Paulus is a historian from Michigan and author of The Slaveholding Crisis: The Fear of Insurrection and the Coming of the Civil War.