At one point during his 1969 run for mayor of New York City, the novelist, essayist, filmmaker, and impenitent outlaw of polite society Norman Mailer described the source of his electoral advantages, such as they were, with great precision. “I can look without horror upon any man whose hand I have to shake. The difference between me and the other candidates is that I’m no good, and I can prove it,” said Mailer, who lost the election (of course) but contributed a valuable insight into human nature. The public will always be drawn to a figure who concedes, perhaps even revels in, his imperfections.

In the case of Mailer, a campaign predicated on an open acknowledgment of sins was not enough to install him at Gracie Mansion, but when it came to legendary Cincinnati Reds player and manager Pete Rose, it surely would have catapulted him into the Hall of Fame — were such a thing open to fan vote.

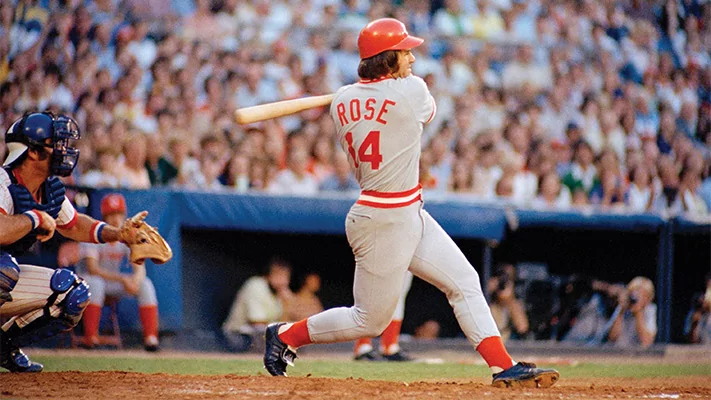

Rose, who died on Sept. 30 at the age of 83, possessed a gift for the game that was beyond dispute: From 1963 to 1986, while playing with the Reds and, briefly, several other clubs, he acquired MLB records for most hits (4,256) and games played (3,562), among other accolades. His accomplishments include 17 All-Star appearances and a trio of World Series championships. He did not exude elegance and elan as much as brio and brawn: A switch-hitter, he hunkered over the plate in a squat that came to be one of his signature moves. Plunging toward the base was another. Yet Rose was made a permanent exile from the MLB in 1989, when, as manager for the Reds, it was established that he had gambled on the game, a charge that he contested with the same mixture of shamelessness and self-confidence with which he played: Sure, he placed bets on other sports, but on baseball? On the Reds? No way, nuh-uh, not a chance. “I’m happy to look into the camera now,” Rose said, conspicuously bobbing his head and not looking into one camera in particular, in a piece of old news film, “and say I never bet on baseball and I never bet on Cincinnati Red baseball.”

More than a decade would elapse before Rose admitted to the baseball betting that had resulted in his banishment. “That was my mistake, not coming clean a lot earlier,” Rose said in a painful 2004 interview with Charlie Gibson on ABC’s Primetime. “I bet on baseball in 1987 and 1988.” He also bet on the Reds while serving as the team’s manager. “I believed in my team. I mean, I knew my team.”

And Rose’s fans knew Rose. Let’s face it: Most people, including those who believed his ostracism from the game to be unjust, probably accepted the gambling accusations to be true long before he came clean. To state the obvious, Rose never presented himself as a choir boy, and placing wagers on his sport just seemed like something he would do. He was a roughneck — “Charlie Hustle,” as he was dubbed. As good as he was on the baseball diamond, he was still no good, and he could prove it. People loved him all the same — maybe in spite of, probably because of, his wayward ways.

But not everyone loved him for it, and one of the people who loved him least wielded the power to evict him from baseball forever. MLB Commissioner A. Bartlett Giamatti came to the game with an unusual pedigree: A Boston native, he was born into an academic family, and he became a revered scholar in his own right. Renaissance literature was his bag. His books included a deep dive into Edmund Spenser’s epic poem The Faerie Queene. At first glance, Yale University, from which he graduated, at which he taught, and for which he served, from 1978 to 1986, as president, might be said to be the institution that defined his life. But there was another institution that competed for his love and devotion: baseball.

“The game begins in the spring, when everything else begins again, and it blossoms in the summer, filling the afternoons and evenings, and then as soon as the chill rains come, it stops and leaves you to face the fall alone,” Giamatti wrote in his famous 1977 essay “The Green Fields of the Mind.” “You count on it, rely on it to buffer the passage of time, to keep the memory of sunshine and high skies, and then just when the days are all twilight, when you need it most, it stops.”

In one of the more improbable but welcome career transitions in modern American life, Giamatti parlayed his enthusiasm for baseball, and his enthusiastic writings about it, into a second career: He left his home turf of Yale to become the president of the National League (1986-89) and then, for five months in 1989, many hours of which were undoubtedly taken up with the Rose mess, the commissioner of MLB. To ascertain the validity of the allegations against Rose, Giamatti tapped attorney John M. Dowd to produce a report on the matter, the conclusions of which were unambiguous: When it came to Rose betting on baseball, the verdict was “guilty.”

“The banishment for life of Pete Rose from baseball is the sad end of a sorry episode,” Giamatti said in announcing Rose’s “lifetime ineligibility” on Aug. 24, 1989. “One of the game’s greatest players has engaged in a variety of acts which have stained the game, and he must now live with the consequences of those acts.”

After a lifetime of getting by on his athletic grit and personal charm, Rose encountered in Giamatti an opponent who lacked the public’s fondness for a rascal. Author James Reston Jr. wrote an entire book contrasting these two profoundly unalike figures, Collision at Home Plate: The Lives of Pete Rose and Bart Giamatti. For Reston, Giamatti’s denunciation, his “simple and clear moral position,” had a ferocity and clarity worthy of the Old Testament. “Adam had been banished from Eden,” Reston wrote. “Cain had been banished from the presence of the Lord. In the Book of Samuel, the ‘King doth not fetch home again his banished.’ It had happened to Cicero in ancient Rome, and in that time, so dear to Giamatti, banishment implied the confiscation of property, as it now did for Rose in the present day.” Reston added: “A scourge had been cleansed from the hallowed national game. Baseball was safe in Giamatti’s hands, and that was good.”

In the final stunning act of this tragedy, Giamatti died on Sept. 1, 1989, but baseball, at least as far as this one “sorry episode” was concerned, did right by its fallen leader: Despite Rose’s subsequent confession and widely publicized appeals for absolution, he was never granted reinstatement. Speaking with Gibson in 2004, Rose admitted that despite his decision to admit to gambling on the game, there was no guarantee that MLB’s then-commissioner would rescind the ban. “So I could be sitting out on the limb for the next 20 years,” Rose said back then, and that’s exactly what happened.

For some, to take Rose’s punishment seriously in the 21st century may seem naive, old-fashioned, out of step. After all, this is a sport that has been stained mightily — by the steroid scandal, by the HGH scandal, by other gambling scandals — since Giamatti’s biblical imposition of judgment on the Reds’ greatest player. Yet Giamatti conceded, in banning Rose, the persistent fallibility of the game’s participants. “It will come as no surprise that like any institution composed of human beings, this institution will not always fulfill its highest aspirations,” Giamatti said, but as he saw it, that does not remove its mandate “to strive for excellence in all things and to promote its highest ideals.” Indeed, the fact that the ban outlived both Giamatti and Rose makes it a rare example in modern life of words having true and lasting meaning: It ended up being a lifetime ban, after all.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

In the age of Donald Trump, conservatives increasingly find themselves excusing bad behavior in the name of advancing noble causes. This is a regrettable but inevitable state of affairs: Most elections of consequence come down to two candidates, and voters must bear in mind that even flawed candidates, like Trump, have the capacity to do great good, as Trump did when he nominated the Supreme Court justices who helped overturn Roe v. Wade and as he may do again if he implements a foreign policy that settles an unstable world. Paradoxically, we have to endure flawed men in politics because the stakes are too high not to. What if, in rejecting a presidential candidate because of his or her flawed character, we reject the person who might avert World War III? On the other hand, we should not tolerate flawed men in pursuits like baseball because the stakes are not high at all. Banning Rose from baseball did not lead to global conflict. It simply removed a bad actor from a wonderful game. Perfection is most easily attained in trivial pursuits.

“The matter of Mr. Rose is now closed,” Giamatti said 35 years ago. It stayed that way, and now it surely is. If there is ever a remake of that great baseball movie Field of Dreams, Rose would undoubtedly be among the deceased giants of the game hidden away in all that corn — but it was a good thing he was never allowed back on a real-life baseball diamond.

Peter Tonguette is a contributing writer to the Washington Examiner magazine.