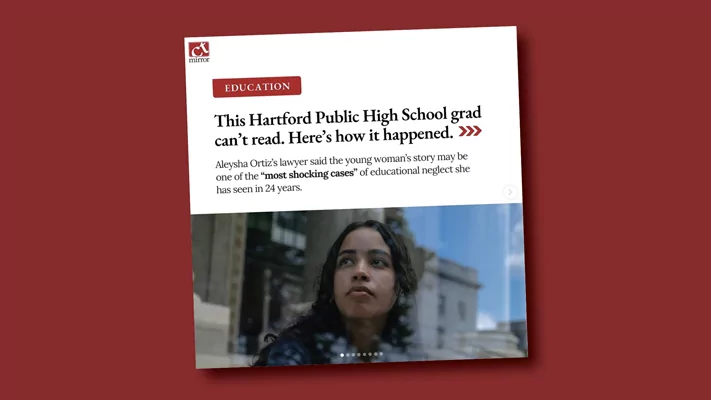

Aleysha Ortiz is a freshman at the University of Connecticut. She made the honor roll at Hartford Public High School. And according to a lawsuit Oritz has filed against Hartford Public Schools, she can’t read most one-syllable words.

“I should have had the help of a special education teacher, a paraprofessional, lessons designed to meet me where I was and challenged me, speech therapy, and occupational therapy,” Ortiz recently said in a letter composed for her to state legislatures. “I felt like no one cared about my future because I didn’t receive those supports.”

Ortiz’s mother, Carmen Cruz, migrated with Ortiz and three of her other children from their native Puerto Rico to Hartford when Ortiz was 5. “We heard Connecticut had the best education and things like that, which is one of the reasons we came to Hartford,” Ortiz told the Connecticut Mirror.

Neither Ortiz nor her mother spoke any English when they arrived in Connecticut, but the Hartford public school system quickly identified Ortiz as having both a speech impediment and ADHD. As required by federal law, Hartford Public Schools then prepared an individualized education plan, or IEP, which identified Oritz’s current skills, her educational needs, and what accommodations or services were needed to help her reach her specific educational goals.

Unfortunately, it appears the plan was never followed. By her own admission, Ortiz “struggled with behavioral issues,” including throwing things in the classroom, screaming, and running away from instructors. On several occasions, school security had to be summoned to remove her from the classroom by force. Instead of teaching Ortiz, she was given other tasks to occupy her time like organizing books or tracing letters.

Despite annual meetings with her mother to approve and update her IEP, nothing was ever actually done to educate Ortiz. Nor was she ever held back a grade. Instead, she was passed along to the next teacher and eventually the next principal. By seventh grade, she spent so much time in the principal’s office due to behavioral problems that her principal said she had “shared custody” of her.

In high school, Ortiz figured out how to use Google Translate to help navigate her classes even though she couldn’t read. The app allows users to photograph text that the phone can then read aloud to the user. Normally students are not allowed to record teachers or use smartphones in class, but Ortiz’s IEP, updated each year, specifically allowed her to use her smartphone for this purpose. So it does appear that at least some of her IEP was being followed.

Ultimately, however, Ortiz was never given personalized reading instruction by the Hartford public school system. It was not until the month of her scheduled graduation from high school that she was offered 100 hours of reading intervention over the summer at the district’s central office. Ortiz declined those services, however, doubting that Hartford Public Schools had the staffing to provide the services. Instead, Ortiz opted for a mandatory transition to college program offered by UConn that ran from 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. every day throughout the summer.

Hartford Public Schools does not come out looking good in this story, but it is not the only villain. Parents, even parents who can’t speak English, must realize something is wrong if their child can’t read but they keep being advanced to the next grade. Teachers at some point have to take responsibility for the students in their class instead of passing them along to be the next person’s problem.

But ultimately, the real villains here are the voters who pile mandate after mandate on schools with no increase in funding to meet them. Special education teachers cost money. Paraprofessionals cost money. Complying with federal regulations and paperwork for special needs children takes time and resources. And everything becomes even harder and more expensive when parents and students can’t speak English.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

President Joe Biden has released hundreds of thousands of migrant children into the United States, and almost all of them can’t speak English. Who is going to pay for all the extra staff required to educate them and give them the extra services required by federal law? Who is going to compensate the children born here whose classes are disrupted by accommodating these children?

If things don’t change, there are going to be a lot more college freshmen who can’t read a single syllable.