In 1914, Vogue wrote that even the idea of American fashion was “too awful to contemplate.” By the postwar period, pathbreaking fashion executive Dorothy Shaver told the New York Times that “the American Look will be copied widely. … Just as our movies and jeeps are distinct contributions, our casual pretty clothes will exert international influence.” Soon, she added, women all over the world would take it as a compliment to be told, “My dear, you look so American.”

Grabbing some milk today in London, I passed a British woman in her 20s wearing an Abercrombie sweater, Yankees fitted, and what looked like a Gap denim jacket. How right Shaver was. Today, whether in London or the high street of almost any city in the world, one can dress, and dress well, in American fashion brands from head to toe. To wit: After that woman, a man walks past me wearing a sweater from Aime Leon Dore, the New York-based men’s fashion house, and a pair of Made in USA New Balances 990v6, designed by fellow New York menswear hero Teddy Santis. Shortly after, on my way to grab a coffee, I pass the new window display in Boss, double denim with a camel overcoat, and I don’t mind it, but it seems a bit unimpressive compared to the overcoats of Todd Snyder. Why am I thinking about coats anyway? It’s boiling. I’d be better suited picking up a Ralph Lauren polo.

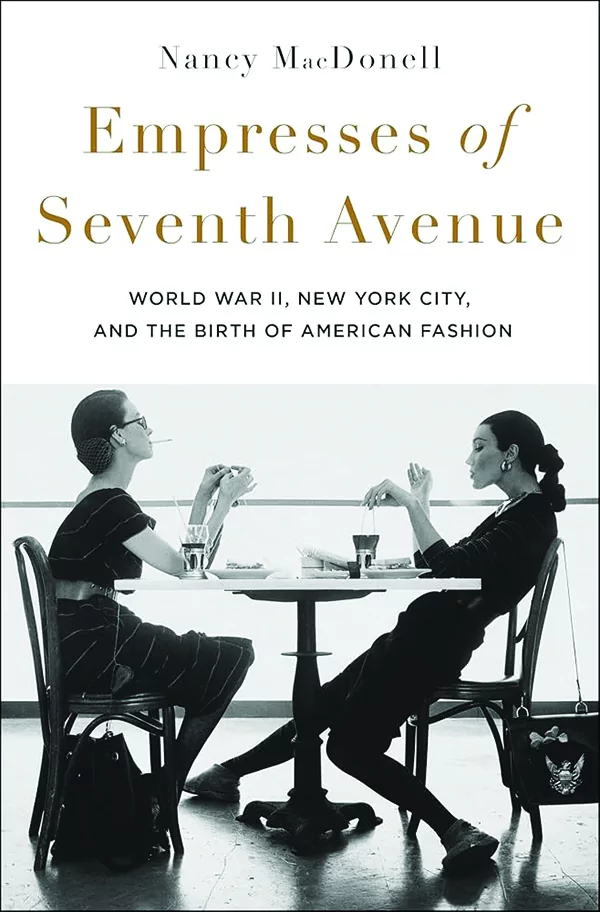

Though there has been much written about the rise of Ralph, Halston, and American prep, Empresses of Seventh Avenue, by fashion journalist and historian Nancy MacDonell, tells the earlier story that allowed all that to happen, the tales of the various women who showed that American fashion didn’t need to bow to and copy the French but could stand on its own.

The ubiquity of the “American Look” is not simply a downstream effect of American cultural dominance but the result of a decadeslong industry and marketing push. The same process of mythmaking created “The French Legend” centuries earlier, the “widespread belief that all beautiful clothes were made by French couturiers and all women wanted those clothes.” As MacDonell writes, the Seine didn’t carry divine sartorial providence. Rather, France’s fashion domination comes from a campaign by Louis XIV, who hoped to build a local industry, show off his riches, and set a standard for royal dress that demanded the attention and money of France‘s wealthy families. It was man and money that built Paris as a fashion capital. And it was working New York women who challenged it.

For much of the 19th century, New York’s fashion industry was much like today’s Canal Street — American dressmakers calling themselves Madame, copying the latest from France, with a few modesty-enhancing tweaks. It was successful, for a time. But the various campaigns for “American Fashion for American Women” were not simply vigorous patriotism. Designers, journalists, and mayors felt that American women needed clothes that were more practical, easy to wear, and inexpensive than the French could muster. So, they started making their own. With the fall of Paris in World War II, they had the perfect opportunity to make that happen.

Fashion history books can be hit and miss. Many are too dry, fashion history books for fashion historian readers, and others are too dishy, catty, and insubstantial. Empresses of Seventh Avenue is neither — a rich, entertaining walk through a part of history most are unfamiliar with, written so it is accessible for the general reader but still detailed enough for the fashion nut. Each chapter is the story of particular women — from the designers Elizabeth Hawes and Claire McCardell to the editors Edna Woolman Chase and Carmel Snow, and Lord & Taylor’s Dorothy Shaver and Marjorie Griswold, among others — and each is meaningfully distinct yet flows easily along, naturally leading into the next.

Reading through, it’s regularly astonishing to find how many of today’s dominant trends were started almost a hundred years ago. Leggings, ballet flats, workwear, the capsule wardrobe, and what became modern athleisure all come up. Most fundamentally, after the American Look, the uber-rich dressed very similar to the middle class. You don’t get hipsters in SoHo wearing Carhartt double-knees without McCardell or the fashion press that covered and advocated her, and the department stores that stocked her clothes.

One of the great strengths of the book is that the titular “Empresses” aren’t just designers but editors and businesswomen. This is a book about fashion but also a story of the rise of American marketing, how war changes countries, and the wonderful entanglements of capitalism. Each chapter balances out biography with historical and social context, and their particular impact on American dress, along with quick diversions into interesting related points, such as the fall of Paris, the rise of Macy’s, storefront marketing gimmicks, or the growth of ready-to-wear. Ernest Hemingway gets more than a few mentions.

MacDonell also has a great knack for throwing in little humanizing details that add tragedy and personality to even briefly mentioned side characters. There’s Mayor Fiorello La Guardia and how he advocated his city’s nascent fashion industry despite his own disheveled state. Or Hattie Carnegie, whose regularly scheduled trips to Paris weren’t interrupted by her wedding, heading off mere “hours after she said ‘I do’ to husband number two.” Andy Warhol throws a bathtub through a department store window.

The only knock against the book is its timing, coming out a few months after Julie Satow’s When Women Ran Fifth Avenue, which also covers Shaver and Lord & Taylor. For those who’ve read Satow’s book, it will undermine the novelty of MacDonell’s best chapter. But Empresses is the better book.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Ross Anderson is the Life Editor at the Spectator World and a tech and culture contributor for the New York Sun.