Review of The Age of Palmer: Pro Golf in the 1960s, Its Greatest Era by Patrick Hand

Michael Taube

The modern game of golf can be traced back to 15th-century Scotland. Since then, the Game of Kings has witnessed strange weather conditions, wildlife invasions during tournaments, a ban by King James II of Scotland in 1457 for serving as distractions to archery practice for the battlefield, and the Masters being turned into a cattle farm during World War II. But the game thrived, and so did the personalities of its greats. Sam Snead, Ben Hogan, Tom Watson, and Bobby Jones all transformed the game with their exceptional play and media-savvy approaches. Modern talents such as Phil Mickelson, Hideki Matsuyama, Sergio Garcia, and Tiger Woods became larger than life, too.

What’s the greatest era of golf? It’s hard to answer, though Patrick Hand’s new The Age of Palmer: Pro Golf in the 1960s, Its Greatest Era tries. It’s an intriguing examination of the legends who dominated this game: Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus, Lee Trevino, Gary Player, and others. The author, a lawyer by trade, contributes to Global Golf Post and has written for Golf Journal, the Washington Post, LA Weekly, and the Washington City Paper. He has a unique talent for combining extensive golf research, interviews, and storytelling into fascinating, light-hearted pieces.

LEVEL THE PLAYING FIELD FOR INDEPENDENT MEDIA

In Hand’s view, the sport began to evolve in the 1960s. “Golf became colorized, both on television and in glossy magazines such as Sports Illustrated and Golf Digest,” he wrote, and had a “different, livelier vibe than before.” Most PGA Tour members, with the notable exceptions of Palmer and Nicklaus, “car-pooled to tournaments, shared motel rooms, and ate in cafeterias. They had a middle-class lifestyle, not much different than many of the fans who attended the tournaments.” Golf also experienced significant “cultural change,” with the PGA of America going from being “only open to members of the Caucasian race” in 1960 to having three African American golfers (Lee Elder, Charlie Sifford, and Pete Brown) who became “tour mainstays” by 1969.

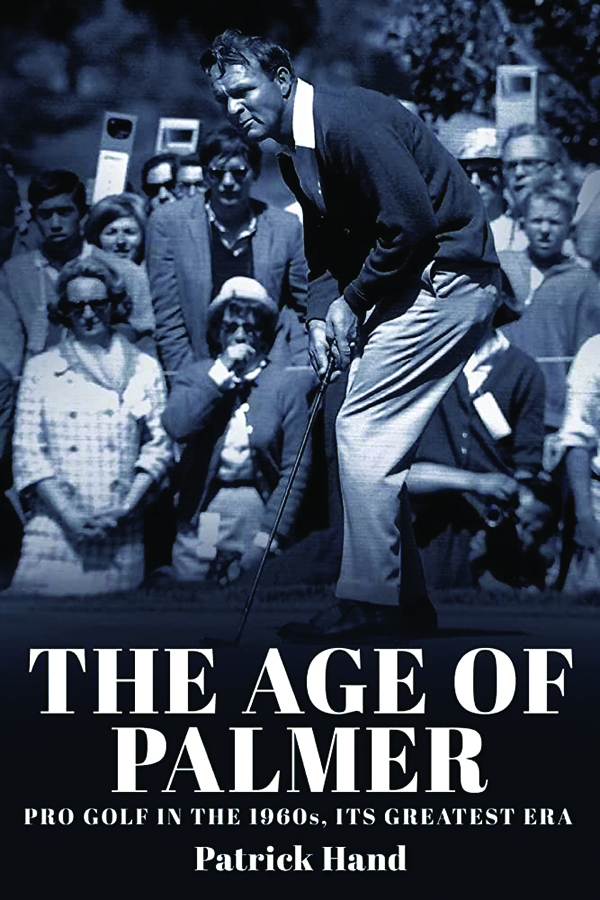

Hand readily admits The Age of Palmer isn’t an “encyclopedia of pro golf.” The sport’s growth and development in the 1960s are seen through the players’ eyes and multiple rounds of golf. Palmer, for instance, played a memorable tournament to win his second Masters in 1960. He birdied the 17th and 18th holes to claim a one-stroke victory over Ken Venturi. The crowd was in the palm of his hands with every agonizing twist, turn, and swing. “For almost an hour, Palmer had the national television audience almost all to himself,” Hand writes. “They saw his powerful corkscrew swing and unusual putting stance with his knees touching. They saw him smoking cigarettes between shots, stalking the greens, and placing his hands on his hips as he viewed the next shot.”

This was the early rise of “Arnie’s Army,” the loyal fan base who followed their champion through thick and thin. “He was the No. 1 king in the sports world,” Frank Beard said in an interview.

Palmer’s stardom made golf on television and was made by it. Now that the sport was showbiz, it needed drama driven by conflict, and few rivalries in golf have compared to Palmer’s competition with Nicklaus, personally friendly but professionally intense. They were joined at the heights of stardom and athletic performance by the likes of Lee Trevino. The Dallas assistant golf pro and ex-Marine started his PGA career by finishing fifth at the 1966 Panama Open. By ‘68, he battled Bert Yancey at the U.S. Open and saved his opponent from a penalty and possible disqualification when he noticed the coin marker he had asked him to lift hadn’t been replaced. This was a level of sportsmanship that defined the man known as “Mighty Mex.” He would ultimately beat Nicklaus, the defending champion, and win his first major.

“I’m a golfer who never knew who Sam Snead, Ben Hogan, [Gene] Sarazen, [Bobby] Jones were until I went on tour,” Trevino recounted. “I came up in a house with no plumbing, no electricity — we didn’t have televisions, we didn’t have radios, we didn’t have newspapers — and golf wasn’t one of my deals, so I sure wasn’t watching anybody.”

The Age of Palmer contains some other eye-opening stories about what the majors were like back then. Namely, shockingly normal guys playing a shockingly accessible sport in the age of television’s ascendance. Sam Snead admitted he threw the 1960 World Champion Golf made-for-TV event against Mason Rudolph. It was with “the best of intentions” because he realized he had 15 golf clubs in his bag instead of the regulation 14, meaning “he had lost the 11 holes he already had played.” We find one of the best golfers in the world, Gary Player, describing how he traveled to some tournaments in a Greyhound bus. (He also posited some eye-raising remarks after winning the 1961 Lucky International Open. The South African discussed how his diet consisting of “honey, nuts and dried fruit” helped lift up his game, whereas he felt the “trouble with most Americans, they eat too many greasy foods.”)

Palmer, as it happens, won the final two PGA tournaments of the 1960s. He would earn several more tournament victories and dominated the Seniors Tour before ending his career. When he died in 2016, his ashes were scattered over the Latrobe Country Club, and a “rainbow appeared.” It’s a poetic ending to Hand’s enjoyable book and the golfer “who, more than any other player, defined pro golf in the 1960s” and made this great game even greater.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Michael Taube, a columnist for four publications (Troy Media, Loonie Politics, the National Post, and the Epoch Times), was a speechwriter for former Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper.