Blanche: The Life and Times of Tennessee Williams’s Greatest Creation reviewed

Malcolm Forbes

At the dark heart of each of Tennessee Williams’s finest plays is at least one damaged character whose plight powers the drama. Williams called his gallery of lost causes “my little company of the faded and frightened, the difficult, the odd and the lonely.” That company includes Brick in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, who only achieves inner peace when a click goes off in his head, “turning the hot light off and the cool night on.” But that click doesn’t come naturally: “I got to drink till I get it.” There is also the defrocked and disgraced Reverend Shannon in The Night of the Iguana, “a man at the end of his rope who still has to try to go on” but who continues to crash and burn and rail against the God he has forsaken in an isolated Mexican hotel.

Then there are Williams’s bruised and brittle women: Laura in The Glass Menagerie, as fragile as a piece in the eponymous collection of figurines; Serafina in The Rose Tattoo, a reclusive widow who learns the hard way about her late husband’s infidelity; and Catharine in Suddenly Last Summer, who faces a lobotomy to erase the memories of her cousin’s murder.

However, Williams’s most tragic iconic creation is Blanche DuBois from A Streetcar Named Desire. The sad, washed-up Southern belle who depends on the kindness of strangers and who attempts to salvage her dignity and sanity through a steady supply of affectations, flirtations, and illusions remains an endless source of fascination for audiences. Last year marked the 75th anniversary of her first stage appearance.

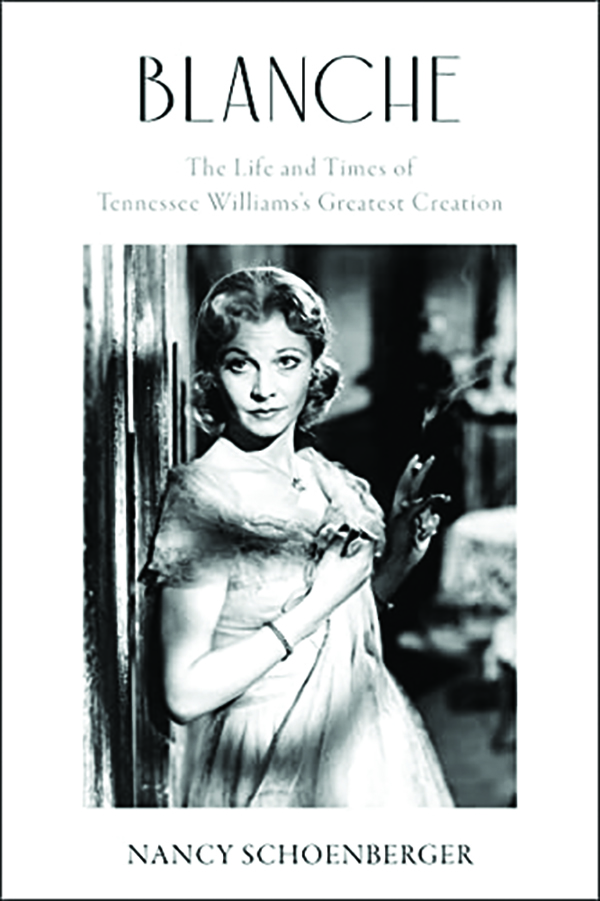

A new book by author and poet Nancy Schoenberger examines the lasting appeal and cultural impact of the character Williams’s biographer, Donald Spoto, described as a “gentle, needy, spiritual but manipulative sensualist.” Blanche: The Life and Times of Tennessee Williams’s Greatest Creation is an original work that, refreshingly, prioritizes protagonist over play. Rather than add to the stack of books that dissect Williams’s masterpiece scene by scene, Schoenberger provides an insightful case study of Blanche through the performances of seven different actresses who played her and one who partly inspired her. Along the way, she assesses what each woman brought to the role, what they took away from the experience, and the ways they helped Blanche to evolve and endure.

Schoenberger begins her book with Rose, Williams’s traumatized sister and creative muse, whose DNA can be found in Blanche and several other troubled characters. When Rose developed severe mood swings as a young woman, she was hospitalized and diagnosed as suffering from “premature madness,” today called schizophrenia. Her condition worsened, and she was institutionalized for the rest of her life. She always maintained she had been sexually abused by her boorish, feckless, alcoholic father, a claim her mother constantly dismissed. Schoenberger draws a comparison here with Blanche, who at the end of the play is escorted to an asylum after her antagonist, Stanley Kowalski, rapes her — a “story” her sister, Stella, refuses to believe.

From here, we move on to the actresses. The first person to portray Blanche was Jessica Tandy. The London-born actress had earlier played a Blanche prototype called Miss Lucretia Collins in an early version of Streetcar, a one-act drama titled Portrait of a Madonna. At the Ethel Barrymore Theatre on Broadway on Dec. 3, 1947, Tandy gave a polished and professional performance as the more complex Blanche. Unfortunately, she was, according to Schoenberger, “outdazzled” by her co-star, the young and then-relatively unknown Marlon Brando.

Brando would of course reprise his role as Stanley in Elia Kazan’s magisterial 1951 film adaptation. Tandy was replaced by another English actress, Vivien Leigh, who remains for many the quintessential Blanche and who won an Academy Award for her efforts. In Schoenberger’s view, Leigh’s “powerful, heartrending” portrayal so brilliantly evokes Williams’s most famous character that “all subsequent actresses have had to, in some way, reckon with it.”

Instead of retreading old ground with a commentary on her acclaimed film performance, Schoenberger focuses on Leigh’s first outing as Blanche on the London stage two years before. Directed by Leigh’s husband, Laurence Olivier, the production was a box-office success, but playing Blanche reduced the actress to a quivering wreck. During the eight-month run, Leigh was prone to indiscretions and affairs and would roam the city’s less salubrious neighborhoods after dark. She later admitted that the role tipped her over the edge. Schoenberger argues that Leigh’s “nascent bipolar illness uniquely suited her to fully embody Blanche.”

The Swedish actress Ann-Margret, who played Blanche in an ABC made-for-TV movie in 1984, regarded the character as “a nymphomaniac, an alcoholic, and a psychotic.” Despite these failings, the actress exuded confident sexuality in the role. Schoenberger sees Ann-Margret’s Blanche as “less a wounded bird and more of a steel magnolia,” not content with her lot but still prepared to deploy her survival instincts to defy the odds and find a safe haven — or, as Blanche puts it in Scene 9, “a cleft in the rock of the world that I could hide in.”

Jessica Lange played Blanche onstage and in film, and each time she brought out what she considered underpins the character’s suffering, “this devastating, terrible aloneness.” Patricia Clarkson, a native of New Orleans, channeled Blanche’s Southern sensibilities while approaching the character as “part hooker and part schoolteacher.” Cate Blanchett dropped some bum notes with her accent but compensated by expertly teasing out and tapping into all aspects of Blanche’s personality. Finally, Jemier Jenkins, who starred in an all-black production of Streetcar, ensured the emphasis was not on color but on class. For Jenkins, “Blanche, as written, is a snob.”

Schoenberger’s book encompasses other areas. She looks at bold reinterpretations of Streetcar, from Woody Allen’s tragicomedy Blue Jasmine, with Blanchett stealing scenes again in the lead role, to a Simpsons satirical episode titled “A Streetcar Named Marge.” Schoenberger explores key areas related to Blanche, such as her sanity, her ancestral home, her dubious sexual past.

Sometimes Schoenberger wanders off topic and ends up informing her reader more about a feature of the play rather than a facet of its heroine. Her book is at its most absorbing when Blanche is back under the spotlight and when the actresses who played her reveal how the role took its toll on them. Leigh suffered the most, but others were also drained by the ordeal. “I don’t think there is anything more emotional and physically exhausting than this part for a woman,” Lange said. “It destroys your life when you play that part. You never really recover from it, and everybody who’s ever done it knows,” said Clarkson.

“We are still trying to solve the mystery of Blanche,” Schoenberger writes. Like all great characters, she is many things to many people and impossible to finally pin down. Schoenberger’s book might not offer all the answers, but the portraits she presents are beguiling.

Malcolm Forbes has written for the Economist, the Wall Street Journal, and the Washington Post. He lives in Edinburgh.